Replacing petroleum-based products with biobased equivalents is the Holy Grail of the bioeconomy. What are biorefineries doing and how can Biotech help?

‘Biorefinery’ is a buzzword for a cool technological space that draws from GreenTech, Industrial Biotech and SynBio. The core concept behind it is relatively simple: these plants mimic the traditional petroleum refinery, but using biomass instead. This initiative aims to help us meet energy needs while reducing the massive greenhouse gas emissions from oil production. Traditional oil refineries transform crude oil into products that power much of our daily life, not only fuel for vehicles but also a multitude of chemicals that go on to become part of many different endproducts.

Unlike in a standalone bioprocess, an integrated biorefinery can transform biomass into all these different products – making the most of its raw materials and adapting to market conditions. With the biobased industry still very much struggling to be competitive on price alone as we discussed in our bioplastic review, companies in the space must strive to be more flexibile and cut into high-value-added products to help the bioeconomy succeed.

Adapting older Biotech achievements, such as bioethanol from sugarcane or beets, into a biorefinery could make them more efficient. However, biorefineries using food crops suffer from the same sustainability issues as first-generation biofuels. Of course, much of the hype surrounding biorefineries is the possibility (and technical challenge) of using biomass waste – or at least biomass sources that are sustainable. The field’s close relationship with agriculture is one of the reasons there are so many incentives: there is the hope that biorefineries could regenerate rural Europe.

One example of a company working towards this end is Matrica, which relies on plantations of thistle across Sardinia, in previously uncultivated plots of land. From the oil-rich thistle flower and plant biomass, Matrica produces not only energy, but also a range of products perhaps unfamiliar to the normal consumer but essential to much of our daily life – chemical intermediates, plasticizers, lubricants, components of cosmetic products…

Meanwhile, Norway has Borregard, which describes itself as “the world’s most advanced biorefinery”. Listed on the Oslo Stock Market with a market cap of over €800M, Borregard specializes in using wood as a raw material. The resulting specialty chemicals are used in fields as diverse as construction and Pharma.

But it’s not only wood that is a desirable raw material. In “green biorefineries”, grasslands are used instead. For example, Biowert was founded in 2005 in Germany, and now sells both biobased plastics and the grass’s “green juice”, from which amino acids and proteins can be extracted and used as flavours or in cosmetics.

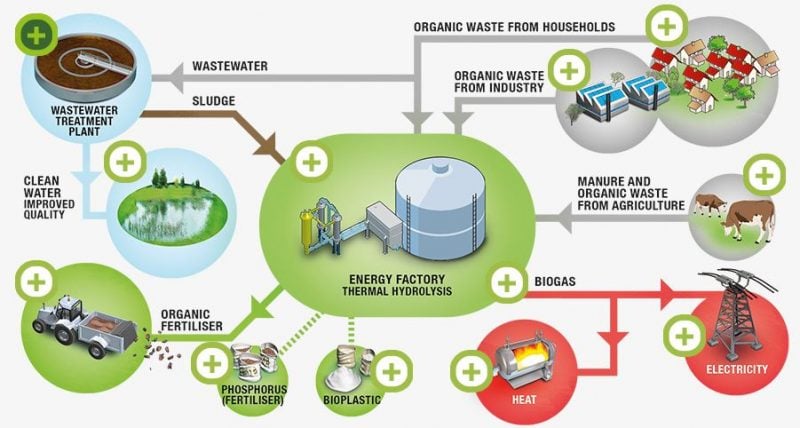

And then there’s waste. In this area, Ynsect (France) is a particularly curious case: instead of enzymes or microbes, it uses insects for the bioconversion step in the refinement process. Insects eat agriculture waste, such as fruit that didn’t meet the standards of supermarkets, and the waste is then transformed into products from aquaculture feed to nutraceuticals. In Denmark, the Billund BioRefinery goes after other waste source, sewage. Besides treating the water, this biorefinery utilizes the organic waste to produce biogas, fertilizers and bioplastics.

Some well-known companies with less “alternative” images are also in the game: traditional players in oil and gas are also moving to biomass. A notable example is Total, the French giant. Back in 2015, it announced it was investing €200M to transform one of its struggling refineries into “one of the biggest” biorefineries in Europe, capable of producing half a million tons per year of biodiesel. BP had its biorefinery adventure with its joint venture Vivergo,which was inaugurated in 2013. However, it later pulled out of the business, which has been losing money for a while. Vivergo can produce up to 240M liters of bioethanol per year, along with animal feed.

The range of biomass that biorefineries can use is broad indeed, and equally broad is the range of products they can make with it. Where does biotech come it? Industrial biotechnology plays a vital role by developing new chemical processes that can and are also used like syngas production; a company in this space has also developed new and improved enzymes that can help break down an even broader range of substrates, enhancing the possibilities of using waste and local resources.

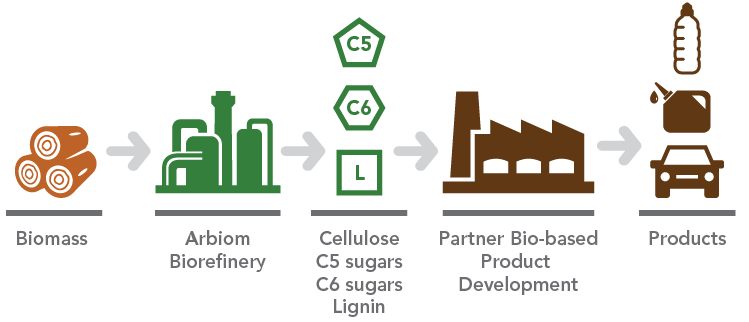

SynBio, a trendy direction in biotech, is proving its worth by upgrading organisms or designing entirely new ones that can produce petroleum-based chemicals like levulinic acid or isobutene to cut down polluiton. Good examples of deals with SynBio are the partnership between Arbiom and Deinove and Novamont’s new bio-butanediol factory. Then there are also other organisms to be explored, such as the very versatile algae, and the EU is financing projects like MIRACLES and D-Factory working towards algae biorefineries.

All in all, the field already has some heavy lifters in Europe, with multinational and even bigger companies moving to invest in their own biobased plants or in joint ventures. Even if recent oil’s historic low prices may have shaken them a bit, they are benefited by ever more stringent policies favoring biobased products. Finally, biorefineries may be one of the best channels for the dynamism of SynBio where, as we’ve seen during last Labiotech Refresh, there’s a new generation of bio-entrepeneurs rising.

Feature Image Credit: Pixabay

Figure 1: White (2015) The Search for Functional Porous Carbons from Sustainable Precursors. Porous Carbon Materials from Sustainable Precursors (doi: 10.1039/9781782622277-00003)

Figure 2: Billund Biorefinery

Figure 3: Arbiom