Although biotech may seem like an industry that has only just gotten started, it was already up and running before the turn of the century. We took a look back at the pre-2000 companies to see how they’re faring.

According to our biotech map, there were 219 biotechs in Europe in 1999. Today, our map contains 1,057 companies, with more added each week. Although there may be biotechs missing from our database, these numbers give an indication of the spark that was lit under the biotech industry at the turn of the century.

The biotechnology industry is particularly difficult to crack, with high development costs and stringent regulations providing obstacles to new companies. As a result, many companies will have disappeared from the industry in the decades before the turn of the century, trying but failing to gain a foothold in their field. Despite this, there have been big successes, with some companies enjoying so much success that big pharma had to step in and adopt them as their own.

We’ve gone back in time and paid a visit to some of the biotechs around Europe that were already with us way back in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s, and followed their journey back to modern day to see how they’ve done so far.

Founded in 1979, French biotech Transgene is one of the oldest biotechs in Europe. It develops vaccines and oncolytic viruses for the treatment of cancer and infectious diseases. Somewhat of a sleeping giant, the company has yet to bring a drug to market, which no doubt contributes to its falling market cap, now standing at €176M since it IPOed at $57M in 1998.

Despite this, the company continues to attract investment and high profile partners. In the last few months of 2017, it raised €14.4M to develop anti-cancer combination therapies, enjoyed positive Phase I results for its hepatitis B vaccine, and dosed the first patients of a Phase I/IIa trial with its ‘next generation’ of oncolytic viruses. Perhaps Transgene’s strong finish to 2017 can spark success in 2018.

Moving into the 80s, Spanish biotech PharmaMar joined the industry in 1986 to develop marine-derived anti-cancer drugs. Despite the 2008 financial crash, the company has grown into Spain’s largest public biotech with a market cap of over €600M. The company already has Yondelis, a compound originally derived from the sea squirt, which prevents DNA repair, on the market for the treatment of soft tissue sarcoma and ovarian cancer. In addition, Plitidepsin and Lurbinectedin are being investigated in Phase III studies for multiple myeloma and resistant ovarian cancer, respectively.

PharmaMar hunts for potential antitumor compounds in our seas and oceans. First, it gathers marine organisms assesses their biological activity in cancers. Second, active substances are isolated and analyzed to determine their chemical structure to help the design of a chemical synthesis process that could be taken large-scale. Finally, testing of the new compound can begin in animal models and, later, in cancer patients.

MorphoSys, based in Munich, Germany, was founded in 1992 and is now one of the world’s leading biotechs working in the antibodies field. Since then, it has developed more than 100 antibodies with 27 in clinical development back in April when we spoke to CEO and co-founder Simon Moroney at our first Meetup in Munich. The company went public in 1999, raising a €26M IPO, and now has over 300 employees and a market cap of over €2.5B.

After 25 years and no approved drug on the market, you’d have been forgiven for getting a little impatient with the German biotech. However, in September, MorphoSys could finally celebrate as one of its antibodies, guselkumab, would be approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. The company has quickly followed this up with an FDA Breakthrough Therapy Designation for its antibody, MOR208, targeted at lymphoma, signaling that this could be the turning point.

With the RNA therapeutics scene really starting to kick off with spectacular results from Sanofi and Alnylam, you could say that Silence Therapeutics was ahead of the game when the company was founded in 1994. It acquired US biotech Intradigm in 2009 and currently has a market cap of £134M (€153M) having raised $58M (€47M) in 2015. In particular, this British biotech is working on RNA interference (RNAi) technology that has the power to selectively inhibit any gene in the genome, for the treatment of life-threatening conditions.

The company focuses on rare diseases, including iron overload disorders, cardiovascular disease, and alcohol use disorder. These programs remain at the pre-clinical stage, meaning, despite its headstart, Silence has been overtaken by Sanofi and Alnylam, which look likely to bring the first RNAi drug, patisiran, to the market later this year.

In 1996, Swedish company Active Biotech jumped into the industry, focusing on medical areas where the immune defenses are particularly important. The company is working on mid- to late-stage clinical programs for autoimmunity, neurodegenerative diseases, and cancer, and has a market cap of over SEK 220M (€22M).

Its lead candidate, laquinimod, is an oral immunomodulator that is being developed for the treatment of multiple sclerosis (MS), Huntington’s disease, Crohn’s disease, and Lupus. However, it has been struggling in Phase III, failing to meet the primary endpoint of an MS trial and cardiovascular side effects being observed with high doses. If it doesn’t get a move on, Active will have to watch out for younger biotechs in the MS field like GeNeuro, which achieved remyelination during a Phase IIb study.

Milan-based biotech MolMed was also set up in 1996 and has since become one of the leading forces in the Italian industry. Its lead product, Zalmoxis, is an ex vivo cell therapy that improves the safety of partially compatible bone marrow transplants, which aims to overcome delayed immune-reconstitution and Graft versus Host Disease (GVHD). In case the patient experiences an adverse reaction to the transplant, the cells are fitted with a suicide gene, HSV-TK Mut2, which is activated by taking an antiviral drug.

MolMed is working on two more candidates: CAR-CD44v6, an immuno-gene therapy, and NGR-hTNF, a fusion peptide that targets the blood vessels that feed tumors. The only blip for MolMed so far came during a Phase III trial of the latter, while it was being tested in patients with mesothelioma. CEO Riccardo Palmisano told me that although over 200 patients did not reach the study’s primary endpoint, it did “significantly improve survival in 198 patients.”

Founded in 1997, Swiss biotech Actelion grew into Europe’s biggest biotech, until it was acquired by J&J in a monster €28B deal 12 months ago. The company continues to focus on a range of diseases like pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), MS, and Clostridium difficile infections. Unfortunately, Uptravi, a drug targeted PAH, is being investigated by the EMA after 5 patients died.

However, out of the deal came Idorsia, a spin-out that kept hold of Actelion’s drug discovery and early clinical pipeline. In addition, the company received €920M (CHF 1B) to get itself started with former CSO of Actelion, Martine Clozel, and the former CEO, Jean-Paul Clozel, in charge.

Jean-Paul spoke publicly of the company’s progress towards its aim of becoming Europe’s biggest biotech: “We are starting on the right track with positive clinical results from two of the assets,” referring to ACT-541468 for insomnia and aprocitentan for hypertension “that will be developed by Idorsia, both progressing to the next stage of their development.”

This Amsterdam-based biotech was founded in 1997 and will no longer have to go very far to get its drugs approved with the relocation of the EMA on its doorstep. Despite its formation in biotech’s ‘prehistoric era’, the company took its time going public, waiting until 2015 to IPO at €33M and has since grown a market cap of over €150M.

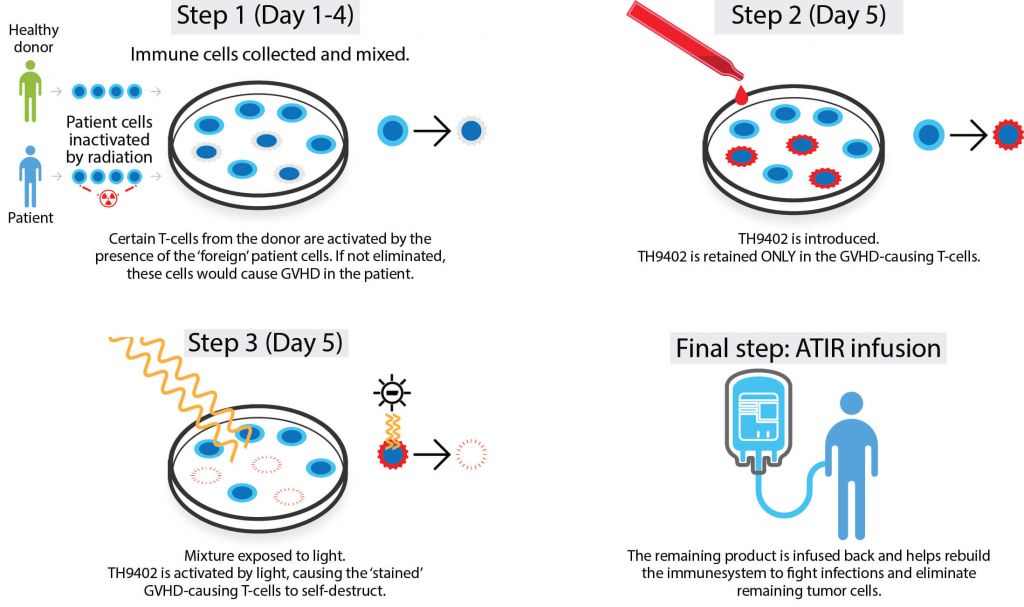

Kiadis focuses on oncology and hematology, developing T-cell immunotherapies for blood cancer patients requiring a stem cell transplant. As with MolMed, the company is working to overcome limitations associated with this procedure, including GVHD, cancer relapse, opportunistic infection and limited matched donor availability.

Its technology platform, Allodepleted T-cell ImmunotheRapeutics (ATIR), removes GVHD-causing T cells from a patient’s new immune system using a selective cytotoxic compound, TH9402, leaving only those that will fight cancer and infection. The company is now solely focused on getting ATIR101, which is currently undergoing a Phase III trial, onto the market.

Belgian biotech Galapagos was also founded in 1999 as a joint venture between Crucell and Tibotec, originally offering drug discovery and services activities. However, in 2014, it decided to focus all its efforts on developing its broad R&D pipeline, which includes filgotinib, now being developed for 10 different indications, and GLPG3221, which has just entered Phase I for the treatment of cystic fibrosis.

CEO Onno van de Stolpe has been with Galapagos since day one, nurturing it into one of Europe’s biggest biotechs, with a market cap of €4.7B. He is confident that filgotinib will succeed but if disaster struck: “Operationally, it wouldn’t be a big issue for Galapagos. With €1.3B in the bank, we can develop our pipeline without being dependent on the stock market, stock price or attracting more funds. Further, we have another 8 molecules in clinical development and another 25 in preclinical development,” he told us.

The company has started putting all of its money to good use, preying on smaller companies like ProSkelia that have the technology it needs to take its candidates towards the clinic.

A round of applause for Genmab, please. Since its inception in 1999, the company has become the largest biotech in Europe – following Actelion’s acquisition by J&J – and recently joined the blockbuster club, as its blood cancer drug, Darzalex, achieved $1B in sales. This has no doubt got big pharma predators licking their lips at the prospect of snapping up the biotech, but Genmab remains fiercely independent.

Jan van de Winkel, CEO, told us that he is keen for the Danish company to continue standing on its own two feet: “I believe that we can build far greater value for stakeholders and patients by remaining an independent innovation powerhouse rather than becoming part of a larger machine.”

And there may be more to come from Darzalex, which is being assessed for the treatment of more indications, including NKT-cell lymphoma, amyloidosis, and solid tumors.

There you go! A selection of ’prehistoric’ biotechs from around the continent that are enjoying varying degrees of success. Arriving early may well put a company in a good position to get onto the market and grow into a powerful force, but without the drive and an effective plan in place, there is no guarantee of success.

Genmab is the standout biotech, a roaring success that has been crowned the largest in Europe and is the proud owner of a blockbuster drug. In contrast, Transgene has been around for almost 40 years but we are still waiting for it to bring its first drug to market.

The success of biotechs working in different fields is, of course, difficult to compare, but when two biotechs are following such different paths within the same area, perhaps it comes down to the strategy chosen by the people at the top. What is for sure, there will be many young biotechs that will be following the lead of Genmab, Galapagos and other role models in European biotech.

Images – red7255 / shutterstock.com; Kiadis Pharma