In just a few years, exosomes have started gaining recognition as a solution to deliver treatments safely and effectively, and as a new approach to regenerative medicine.

For hundreds of millions of years, multicellular organisms have faced many of the same challenges that biotechnology is grappling with today: how best to shuttle biomolecules to and between cells in a targeted and reliable way. Without these abilities, living systems would be ‘every cell for itself’, and cell-to-cell communication and coordination would be nearly impossible.

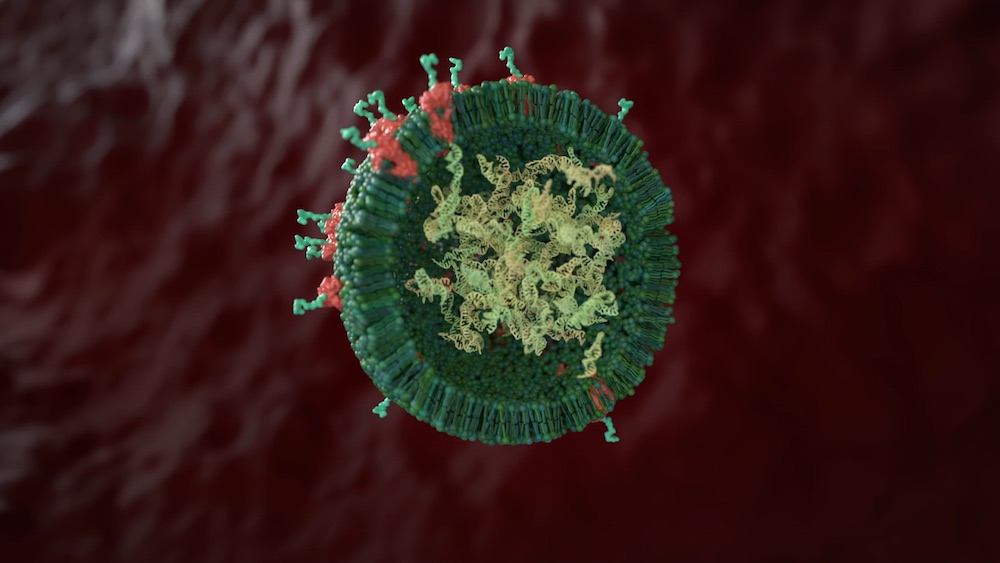

Basic research has revealed that much of this cell-to-cell delivery is carried out by exosomes — tiny lipid bubbles only around 30-100 nanometers across. While small in size and simple in structure, exosomes play crucial roles in fundamental cellular processes such as the regeneration of damaged tissues.

Over the eons, through constant evolutionary R&D, nature has created and optimized these nanocapsules for delivering molecules between and across tissues throughout the body. Today, their elegance and effectiveness at ferrying cargo and sending cellular messages far surpass any human inventions, and their potential for biotech has not gone unnoticed.

Exosomes offer an entirely new paradigm for drug delivery, which is currently a major hurdle for a range of therapeutics. While there are no licensed exosome-based therapeutics yet, the last five years have seen dozens of companies spring up globally to harness these nanobubbles and their time-tested talents.

Good things come in small packages

The design and potency of drugs, from small molecules to nucleic acids to proteins, has seen constant progress over the last few decades. But a key problem still remains to be solved: how can they be most efficiently delivered to the target cells?

It’s not enough to simply create a powerful therapeutic payload in the lab. If you don’t have a practical and safe method of delivering it where it is needed in the body, its real-world applications will always be limited.

There are a few conventional delivery options available, including synthetic lipid nanoparticles and viral vectors — currently being used in the BioNTech/Pfizer and AstraZeneca Covid-19 vaccines, respectively, as well as in a host of protein, RNA, and gene therapies.

But these delivery methods have limitations regarding the areas of the body that they can reach, the amount of cells that they can get to within tissues, and their ability to avoid triggering an unwanted immune response. A simple, safe, widely-applicable delivery tool has remained frustratingly elusive.

Understandably then, the potential of exosomes as a means of drug delivery has gained enormous interest. In the UK biotech hub of Oxford, the company Evox Therapeutics is leading the charge.

“It was one of our founders, Matthew Wood from the University of Oxford, who really was the first one to have the idea of using exosomes as a means to deliver a drug cargo,” Antonin de Fougerolles, CEO of Evox, told me.

“In his case, he was loading small interfering RNA drugs into exosomes and then engineering the exosomes to express a surface protein that would preferentially direct them through the blood-brain barrier to the central nervous system in mice.”

“It was a groundbreaking paper. It really was the first time people had put a cargo into an exosome, the first time people had targeted an exosome, and so it really showed the utility of it as a therapeutic modality,” he added.

Further work by the scientists who would go on to found Evox showed that this same approach could be used for a range of other therapeutic cargos beyond nucleic acids, including enzymes and antibodies. In 2016, Evox was launched to push this science from the lab to the clinic and rapidly expanded from around five staff members in 2017 to over 100 today.

The versatility of exosomes has meant that simply picking which diseases to initially target has been a challenge in itself.

“With exosomes, we have the luxury and the curse of potentially being able to deliver any drug to a wide variety of tissues, so the number of options is quite broad,” said de Fougerolles.

“We picked some of the rare metabolic diseases, such as urea cycle disorders and those that have no curative therapy and where the standard of care is extremely suboptimal. In all of them, we know exactly what we need to deliver to correct the disease. There’s a defective enzyme so we can either deliver that as a protein or [encoded in] an mRNA molecule.”

One key advantage of exosomes over other delivery methods such as viral vectors and lipid nanoparticles is that they can precisely deliver payloads without activating the innate or acquired immune system. This makes repeat dosing much easier, as the patient won’t acquire immunity to the delivery vehicle after the first treatment, which has been a major hurdle for mRNA and gene therapies in recent years.

“We don’t quite know exactly all the ins and outs, but in essence, nature has devised this mechanism over millions of years to be efficient, to be safe, to allow cells to exchange RNA and a full range of proteins from cell to cell. That’s a fundamental advantage,” explained de Fougerolles.

“On top of that is obviously the advantage of being able to engineer all sorts of cargoes into or onto exosomes. We can actually mix different types of cargoes into the same exosome. So if we want to deliver a protein, an mRNA, and a small interfering RNA, we can do that all in the context of a single exosome.”

In February 2021, Evox Therapeutics raised €80M in a Series C fundraising. The year before, the company entered into major partnerships with Takeda and Eli Lilly to advance its lead candidates towards the clinic, focusing on rare diseases that can be treated with protein or RNA-loaded exosomes. The company plans to start early clinical trials in 2022, joining US-based Codiak Biosciences, which launched the first clinical trials of engineered exosome therapeutics in late 2020.

A new tool for regenerative medicine

Aside from their inherent suitability as drug delivery vehicles, exosomes sourced from specific cell types can come pre-engineered towards stimulating the growth and repair of tissues, making them extremely promising for the field of regenerative medicine.

While this field has traditionally focused on cell therapies, exosomes are far less biologically complex and could make regenerative medicine much more accessible.

“Exosomes are a very nice opportunity because they tend to simplify a lot of the bottlenecks for cell therapies. For example, simpler logistics, easier storage conditions, off-the-shelf products… It’s totally different than having a cell product,” said Joana Simões Correia, founder and CSO of Exogenus Therapeutics, a Portugese biotech working on regenerative applications of exosomes.

“The biology has evolved in a way that’s really clever,” said Simões Correia, explaining that in our bodies, the contents of exosomes depend on the specific circumstances of the cell that makes them. “Our mission is to explore this biological context and concept and use it for clinical purposes.”

Founded in 2015, based on research from the University of Coimbra, Portugal, Exogenus Therapeutics initially focused on using exosome-based therapeutics in a gel form for skin wound healing. The firm has since expanded and pivoted towards regenerating lung tissue using inhaled exosomes, in large part due to the Covid-19 pandemic.

Exogenus’ approach consists of extracting natural exosomes pre-loaded with a cocktail of regenerative cargo — mostly small RNAs — from cells in umbilical cord blood.

“This blood is enriched in stem-like cells. What we are doing is using these cells to generate bioactive exosomes. We expose them in the lab to a particular stimulus and we obtain exosomes with regenerative content, which can accelerate wound healing but can also reduce inflammation and cytokine storms in different diseases,” Simões Correia told me.

Normally this umbilical cord blood is discarded shortly after birth. Partnering with a series of Portuguese hospitals, Exogenus has been able to access and use this blood to produce regenerative exosomes by asking parents to donate it instead of throwing it away.

“The exosomes don’t have molecules that would trigger an immune reaction. So what we will have is an off-the-shelf product which, independent of the donor they are coming from, can be applied to any host or any patient.”

“What we are really now putting a lot of effort into are respiratory tract inflammatory diseases. The next steps will be to demonstrate that the exosomes have the potential to solve inflammation, not only for the conditions associated with Covid-19, but also for other lung diseases.”

Exogenus is planning for a Series A investment round to fund the development of its technology. In February 2022, the startup teamed up with Boehringer Ingelheim to develop its preclinical-stage lead candidate in undisclosed indications in regenerative medicine.

Mastering exosome manufacturing

While many exosome biotechs, like Evox and Exogenus, have their own specialized cell lines and manufacturing processes, there’s enormous potential for opening up the exosome field to smaller, newer players. This could be achieved by developing an easily scalable, high-yield exosome manufacturing process that can service the needs of companies and researchers working across a range of therapeutic areas.

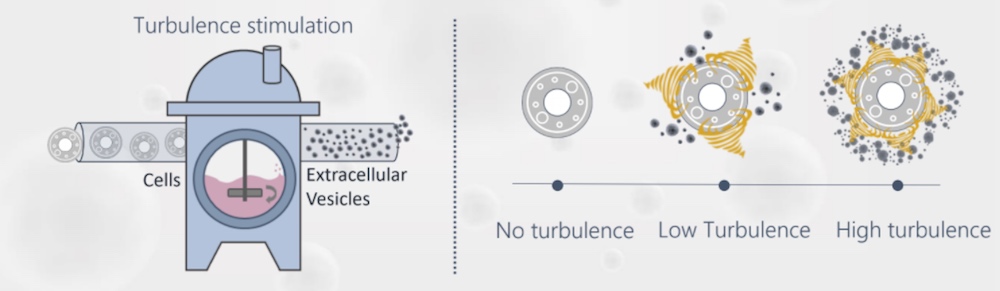

Paris-based Everzom has come up with just such a process by modifying a bioreactor to induce ‘turbulence stimulation,’ a stressful environment that triggers the mass production of exosomes from cells.

“Our founders are more physicists than biologists, and our focus has been to develop better technologies for exosome manufacturing,” said Nicolas Rousseau, Everzom’s COO and co-founder.

“In conventional methods like spontaneous release, you just let the cells live their lives normally and they just continuously release some exosomes. But the yield is very poor, so the most traditionally used method is starvation — you stop feeding the cell, and because of this stress they release more exosomes.”

“[Turbulence stimulation] produces ten times more exosomes, in one-tenth of the time. It’s bio-inspired in that we wanted to mimic the stresses that occur inside the body, and particularly inside blood vessels,” Rousseau explained.

“Based on this technology is our service business model. We’ll partner with other biotechs and provide manufacturing services, purification services, and analytics services. Biotechs will have a cell type that they love, and they’ll come to us and ask us to produce exosomes with it using our process.”

Everzom has tested this process on over 15 different cell types to date, and in every case the mechanical stresses stimulated the release of exosomes at higher than normal levels. The company is also exploring the potential of loading the exosomes with a drug of interest during the production process by mixing it into the culture medium.

With a €2.5M grant from Horizon Europe, funding from the French government, and €1.1M from investors, Everzom’s next steps will be to complete the scaleup of their bioproduction platform. The aim is to produce clinical-grade batches and develop a manufacturing process that can supply phase II and phase III clinical trials.

Dozens of other biotech companies around the world are also racing to make exosomes a clinical reality, both for drug delivery and as therapeutics in and of themselves. Some examples are Exosomics, Carmine Therapeutics, Codiak Biosciences, Vesigen Therapeutics, and Mantra Bio. Additionally, Anjarium Biosciences raised €51M last year to finance a drug delivery system that blends exosomes with synthetic particles. Spurred on by increasing financial backing from big pharma and investors, the field is set to make serious waves over the next few years.

The explosion of interest in exosomes and their potential applications is part of a recurring theme seen over and over in biotech: solutions already exist for many of our biggest problems and basic research is key to finding them. Like many of the most celebrated and revolutionary tools available to biologists today, such as CRISPR, restriction enzymes, and antibiotics, to name a few, exosomes weren’t invented by us, but instead have been borrowed from nature’s toolbox.