Though the psoriasis market is teeming with effective products, companies have developed ways to devise new, more effective modes of treatment.

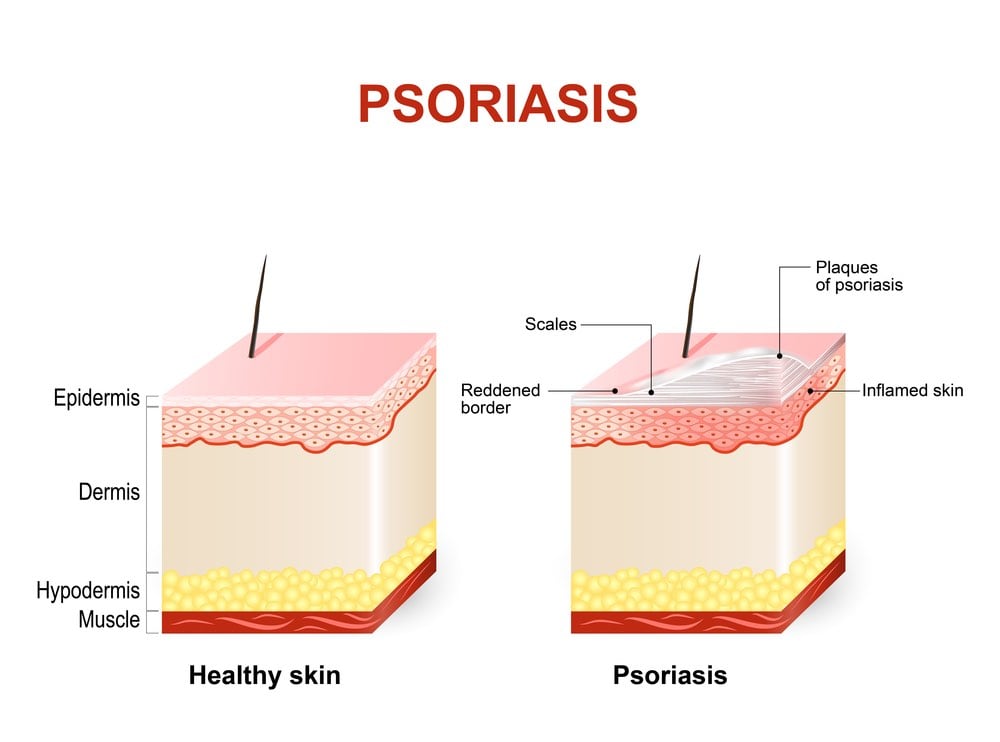

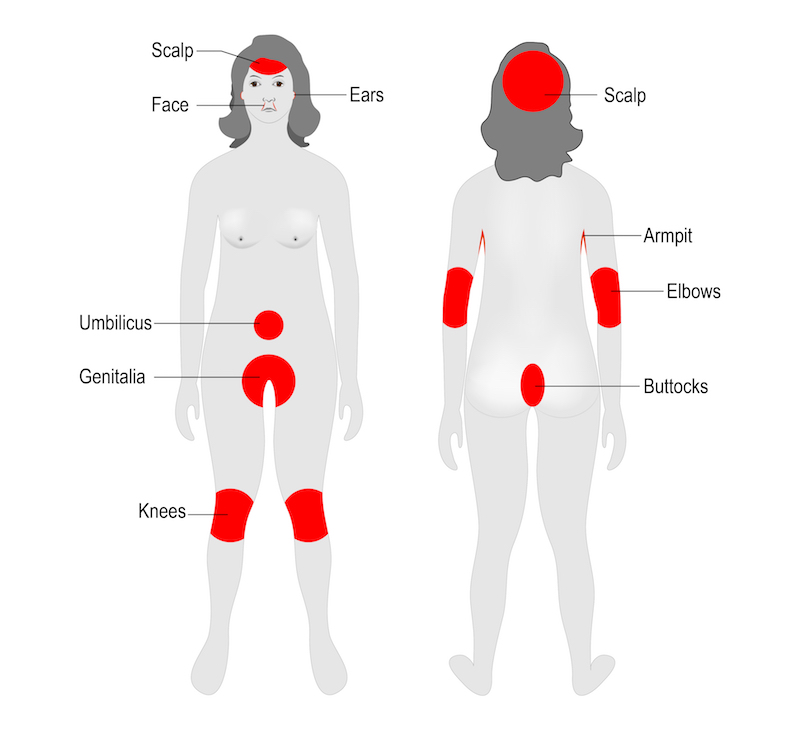

Psoriasis is a common autoimmune disorder that affects the skin, often causing patches of dry, itchy, and painful lesions. In severe cases, people can develop psoriatic arthritis, which can lead to painful inflammation in the joints. According to the World Health Organization, psoriasis affects between 1.5 to 5 percent of the population in most developed countries.

“There has been a tremendous development in the treatment of psoriasis,” says Thorsten Thormann, the Vice President of Research at Leo Pharma, a Danish biotech. “Before, if you were a patient you were to live with your disease and you were marked from it. Today you can be a severe psoriasis sufferer and live with almost clear skin.”

However, Thormann adds, “I think that as in many other diseases, there are two main issues for people suffering psoriasis. One is to get efficacious medicine, and the other is to make sure that the medicine is attractive enough to actually adhere to treatment.”

To address these needs, a number of new, highly effective drugs have hit pharmacy shelves in recent years. In addition, some biotechs are working on ways to improve both convenience and adherence to these medications by turning injections of biological molecules into pills.

Targeted Effects

Anti-TNF antibodies such as Abbvie’s Humira (adalimumab) and Amgen’s Enbrel (etanercept) have long dominated the psoriasis market. However, these compounds have started to face some stiff competition as new drugs have emerged.

Recently, there has been a wave of new biologics targeting interleukin-17 (IL-17). In July, Leo Pharma received permission from the European Commission to market Kyntheum (brodalumab), an antibody that blocks the IL-17 receptor, to treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

“I think when people discovered this molecule, they didn’t think about psoriasis, they thought about IBD, asthma or some of the other immune diseases,” Thormann says. “However, it turned out that the clinical effect was just significantly better in psoriasis, and it’s probably because the pathology of psoriasis is driven by only a few signaling molecules and IL-17 is one of the very important ones.”

Brodalumab, which was originally developed by AstraZeneca, is also being marketed in the US under the name Siliq by Valeant, albeit with a black box warning due to prior evidence that suggested it was associated with suicidal thoughts. Thormann, however, says that his company believes that [this effect] is “related to clinical trial design rather than a real risk.”

Some major players have their own versions of an IL-17 antibody. For example, Novartis’ Cosentyx (secukinumab) and Eli Lilly’s Taltz (ixekizumab) are both approved to treat plaque psoriasis in both the US and the EU.

Janssen, a Johnson & Johnson company with headquarters in Belgium, has taken a slightly different approach to treating the disease. One of the company’s psoriasis drugs, Stelara (ustekinumab), an antibody that targets P40 (a protein that is expressed on both IL-23 and IL-12), has been on the market for a number of years. This July, they received FDA approval to use another drug, Tremfya (guselkumab), an antibody that selectively inhibits IL-23 to treat moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis.

“We have learned over the last five to ten years since Stelara was developed is that IL-23 is actually a master cytokine in the skin,” says Sue Dillon, the Global Therapeutic Area Head of Immunology at Janssen. “It seems to be a central node that’s important in driving the inflammation in the skin, and it’s upstream of many of the other cytokines that we know are important in psoriasis, including TNF-alpha and IL-17.”

In head-to-head studies with both its own drug, Stelara, and Humira, researchers found that patients on Tremfya achieved clearer skin. Janssen is currently in the midst of conducting series of phase III trials with the antibody for psoriatic arthritis, as well as another head-to-head study with the anti-IL-17 antibody, Cosentyx.

Boehringer Ingelheim and AbbVie have partnered to develop their own anti-IL-23 antibody to treat psoriasis as well as other immune conditions, such as Crohn’s disease and asthma.

Going Needle-Free

“There has been remarkable progress made over the last decade for the treatments of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis because of the advent of highly effective biologic therapies,” Dillon tells Labiotech.eu, “[But] there’s still a very large unmet need.” One of these, she adds, is the lack of an oral medication that can deliver drugs with the same level of efficacy as an injectable and the same safety profile.

“The other challenge, quite frankly, is that the bar is extraordinarily high,” Dillon says. “It would be very difficult to construct biologics that are better than the ones we already have. It could happen, but I think probably where the bigger opportunities are in finding oral drugs that recapitulate the activity and the safety of [existing] drugs.”

According to Dillon, Janssen is working on developing oral drugs that will address the same targets and pathways as some of the currently available biologics do. This could help overcome a second unmet need in the psoriasis space, which is that not all patients opt for treatment, even when it’s available. According to Dillon, only around 32 percent of patients with moderate to severe forms of the condition receive this treatment in the United States—and even fewer people do in Europe.

BioLingus, a Swiss biotech, is also working on developing a needle-free treatment for psoriasis. This is based on a platform the company created that allows biological molecules to remain stable at room temperature for long periods of time. “Some of this [was] inspired by what’s happening in the seeds of plants where biological molecules have stabilized for tens or hundreds of years in extreme conditions,” says Yves Decadt, the CEO of BioLingus.

The company also focuses on sublingual delivery, which, according to Decadt, provides an advantage because it allows for more direct delivery to the lymphatic system, providing both the benefit of not requiring injections and the advantage of increasing the efficacy of some formulations. “Essentially, we are targeting the immune system with our unique formulations,” Decadt says. “As a result, we can induce tolerance in auto-immune diseases for a long time, beyond the half-life of the products.”

Biolingus is working on a program based on interleukin-2, for which they are currently conducting preclinical tests for type I diabetes, peanut allergy, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriasis. “For those diseases, we have some animal data already, and we also have anecdotal human data that [suggest] it works in allergy, rheumatoid arthritis and psoriasis,” Decadt says. “So although we focus on one molecule, I would say that this kind of technology you can almost generate what is called a pipeline-in-a-product that’s relevant in multiple indications.” In addition, Biolingus is also partnering with other companies to apply different molecules to their platform.

Right now, the market for psoriasis drugs is teeming with efficacious products. “Psoriasis patients are now in a really good position—the disease is well described, we understand quite a lot about it, and there are very good treatments,” Thormann says. “I think that going forward, finding new more efficacious, injectable biological treatments for treating psoriasis is going to be a challenge.”

Ultimately, however, the goal would be to prevent patients from developing psoriatic arthritis, and eventually, psoriasis itself, Dillon says. “That’s a big piece of what we’re working on.”

Images via zatvornik, Bixi, Designua, Ternavskaia Olga Alibec/ shutterstock.com