The commercial dyeing industry is not known for being eco-friendly, which is something that PILI – a synbio startup based in France – is hoping to address with their color producing microbes. Philip chatted with its CEO, Jeremie Blache, to find out more about the company, its recent successful fundraising round and how its technology could revolutionize the textile industry.

The first synthetic color, mauveine (a shade of purple), was produced by accident in 1856 using petrochemical techniques. Now, around 99% of dyes come from petrochemistry.

The use of modern textile dyes creates toxic pollution and uses large amounts of water. Reducing the environmental impact of commercial dyeing could therefore have a positive global impact.

PILI was founded in 2015 and has a really interesting start-up story, as it originated in the bio-hacking community, where Blache met his co-founders at La Paillasse in Paris.

“It started with curiosity and passion. One day I went into a cellar at this biohacking space. I think I was the first guy who arrived in a suit and tie, as I was doing an internship at an investment bank at the time, but was curious about biotech,” explained Blache.

“My co-founders, who are biologists, did a workshop on how to produce ink from sugar thanks to microbes. We had a lot of success. The public was in love with the idea and a few industrial actors were also interested in this concept. So we made a first business plan and entered a few startup competitions. This was really important as it allowed us to structure our business plan and gain some early stage cash.”

After winning a competition run by Genopole in 2014, Blache decided to work full time on developing the company.

“We started from scratch with no IP and no tech. At the beginning you have to, not fake it exactly, but be pushy about what you can do. How did we convince people? It was very difficult, but from the beginning we developed this technology because people want it. Because the potential is clear, to produce colors not from petroleum but from sugar.”

Last month PILI closed a financing round of €2.5M to help develop its technology further. “It was not easy to close this round, we are at the crossroads of several sectors – biotechnology, but also specialty chemistry, and finally textiles, and it’s not easy to combine these sectors,” commented Blache.

“We got a lot of support from Bpifrance, because our technology could be key for French agriculture. If we succeed in transforming sugar into dyes we can then potentially transform other agromaterials,” he added.

PILI is one of a number of biotechs that are tapping into the crowdfunding space. Blache noted how important this aspect of the company’s funding, which comprises about a third of this round, is to the company. “It shows people are interested in this kind of innovation from the fashion industry,” he said. “We feel support from both the industry and consumers.”

One of PILI’s drivers is the eco-friendly nature of their products and process. Blache expanded on why the production of modern synthetic dye is an environmental issue: “The problem is that the source is a fossil material, it’s polluting to extract and the process to convert this fossil source of carbon to colors is problematic and very consuming in terms of energy. Especially in Asia, where these colorants are used a lot. Now it is changing, because the Chinese government has become much more strict about pollution, but there has been a big problem for a long time.”

He explained: “Our colors are all tested to make sure that they are eco-friendly. We are not developing toxic molecules. In the past chemists didn’t do these tests because they were too costly, but now they are routine.”

Producing things biologically is not always more efficient or safe and toxic molecules can also be produced this way. PILI is currently doing an analysis with a third party to make sure their process is up to scratch.

Blache noted that while it is difficult to do an exact comparison between their process and that of conventional dyeing, PILI’s method definitely uses less water and chemicals. “For 1kg of colorant you need 100kg petroleum, approximately 10kg chemicals and between 1000 and 8000 litres of water. We only need 200 litres of water and we don’t need the petroleum and chemicals we just need 10-30kg of sugar to produce the same amount of colorant,” he explained.

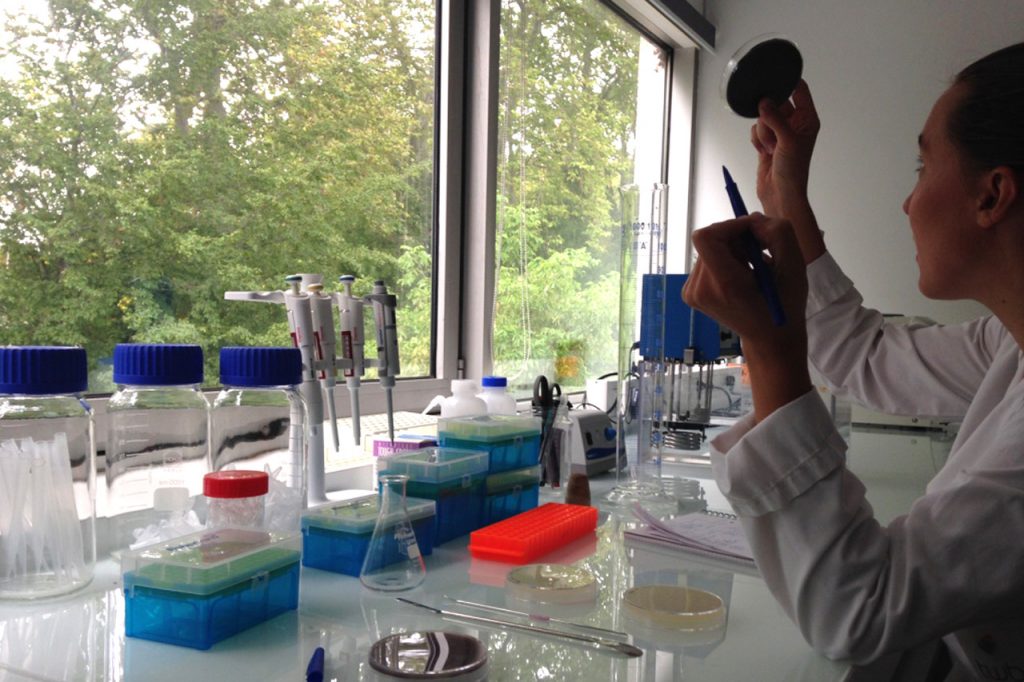

Blache didn’t delve too deeply into the details of the company’s technological process, but essentially the process involves engineering metabolic pathways within the microbial cells to allow them to produce colorant from sugar. PILI has a team of 6 scientists based in Toulouse who are working on optimizing the technology, as well as a team of 4 people in Paris working on chemistry and business development.

When asked about scalability of their process, Blache noted: “For now this is not our main activity. We need to first develop a good product portfolio and select a good market. This takes a long time. Right now we are focused on our product.”

PILI have not yet partnered with any other players in the industry, but Blache said the company is keen to collaborate. “A lot of big players are interested in our technology – chemists, but also big biotech companies. The discussions are interesting because we are not trying to fight them, but we want to disrupt the market with them. So we are very open to discussion.”

Hear it all directly from our interview with Jeremie Blache