Jan van de Winkel co-founded Genmab as CSO and then became CEO to develop the antibody company into a fully independent commercial enterprise. Here’s his strategy.

Since its foundation in 1999, Genmab has become Europe’s largest biotech and a proud parent of a half billion-euro drug, daratumumab. Co-founding CSO Jan van de Winkel played a key role in its scientific success as head of the Danish company’s R&D effort for the first 11 years before he became President and CEO in 2010.

“The Genmab research team evolved out of a team that was already formed and led by me at Medarex Europe, part of Medarex in the US. That team worked with making fully human antibodies with transgenic mice,” he told me.

Creating Genmab with the help of a group of investors in Europe allowed for a key change in direction. “While Medarex kept focusing on the technology platform itself, we took the technology and built a new company that is very much product-focused,” said van de Winkel. Medarex was acquired by Bristol Meyers Squibb in 2009 for $2.3B, but van de Winkel is keen that Genmab will remain independent.

Success like that of Genmab is rare, even more so for an asset-focused company. Curiosity piqued, I talked to him about the company’s strategy to make it this far and his plans for the future.

Could you tell me more about the transition from a development company to a commercial company?

From the beginning, Genmab was always very focused on products rather than technology, because we think that in the end, it’s products that will create a really strong company. But we also wanted innovative products — a number of ours have gotten breakthrough therapy designation.

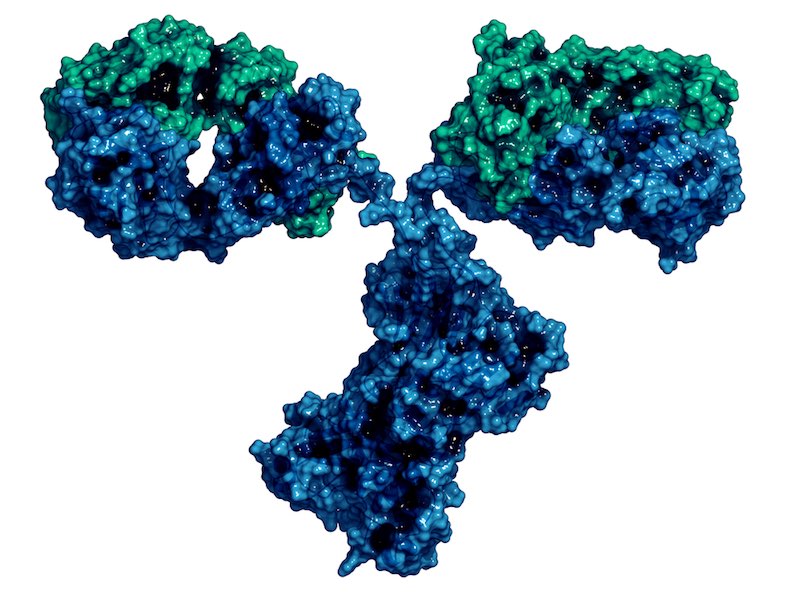

I think the key to Genmab’s success has been its focus on very good science — this is the DNA of the company. We actually understand the biology of antibodies much better than other therapeutic antibody companies. So when we want to create, for example, a bispecific antibody, we can do this in-house.

We’ve been able to create two completely new next-generation antibody technology platforms, DuoBody and HexaBody for bispecific and immune effector function enhanced antibodies respectively, which are very strongly anchored in science via peer-reviewed publications. This means we don’t rely on a single traditional antibody platform anymore. About 80% of our pipeline is based on Duobody and another 10% on HexaBody; the remaining 10% are Genmab antibodies conjugated to toxins — ADCs, that is. Our science focus is what makes us unique.

In 2010 the Board asked me to step up to be the CEO and, it felt like the right time for me so I could refocus the company and make it less dependent on the stock market — because due to the financial crisis in 2008 raising funds via the stock market for a biotech company would be difficult if not impossible. Now, we’re trying to hold on to products and move in the direction of becoming a commercial company to bring our own products to the market.

I’m thoroughly enjoying this: every five years I do something completely new, and I hope that I can continue doing this for a while as CEO.

How do you compare your mouse-based approach to those of companies using phage display?

Phage display is a relatively old technology, and it is challenging to make large panels of high-quality human antibodies with it. Perhaps as a result, there are now four times as many mouse-based human antibodies than phage display-derived antibodies.

The companies using phage display have a different business strategy — more of a fee-for-service one. They may have a large number of antibodies in the pipeline, but many of them will be partnered. We partnered a few of ours to create an income stream that is now ramping up — we’ve been profitable for four years now, and our financial base continues to strengthen each year.

For now, profitability is based on royalties and milestones but very soon our royalties should cover our expenses. Right now, we want to hold on to product rights. At least 50% but ideally close to 100% of the products have to belong to the company to build it into a strong company which is the aim for Genmab — more than the current approximately $13B market cap. We couldn’t do that for earlier products, but this is what you call evolution and it’s what makes us different from other antibody companies.

Are there any other key strategic maneuvers?

We have a comparatively narrow focus now — just on cancer. Originally we started in autoimmune diseases as well, but we realized around 2009 that we needed to focus on just one disease area to develop so-called leapfrog products — drugs that outperform the gold standard. So we only focus on the very, very differentiated candidates, and I think we have formidable execution by bringing these to the market with our novel platforms.

This builds up my confidence, but also those of our shareholders. Over 40% of them are US-based investors, and we couldn’t have gotten this far without them. Europe is a very, very strong powerhouse, but it would have been extremely challenging with European investors alone — American pockets are simply much deeper than those of Europe and biotech is an international business and our shareholder base reflects that.

Would you say that’s what’s holding back European biotech then — comparatively shallow pockets?

I think you need a mix of investors for other reasons. Biotech was built up in the United States, so American investors tend to have much longer time frames for hanging on to a share. It takes time — on average of over 10 years — to fully develop a drug, so the investors need to have a longer horizon to make real success out of biotech investments.

We have a loyal European investor base with Scandinavian, German, Swiss and British investors amongst others, but having US investors as well has made it easier for Genmab to grow in the past five years. Our company has outperformed all the other biotechs, and we need more success stories like Genmab’s in Europe to inspire not just investors but also entrepreneurs to build new strong companies.

Europe has a very good educational base and fantastic science, but we have to support the biotech industry better. It’s a lot stronger now than it was when I started 30 years ago, but I think we need to grow up and help companies to flourish and stay here.

I would argue that Actelion’s acquisition by Johnson & Johnson was a shame because a fantastic company is now leaving Switzerland. We could start by improving the tax structure for innovative companies, — for instance, England and The Netherlands allow companies to pay for the developed product in the end, based on breakthrough innovations. I think something like that would really help.

Thanks for bringing up Actelion. It seems like a good parallel with Genmab as a very successful company, even before it was bought out, with a similarly independent spirit…but it capitulated in the end. What are you planning to do differently?

I believe that we can build far greater value for stakeholders and patients by remaining an independent innovation powerhouse rather than becoming part of a larger machine. Unfortunately, it’s not up to us in the end: as a public company, it’s up to the shareholders.

My previous company Medarex is a good example of why shareholders should stick with a company. The company sold for $2.3B to Bristol Meyers Squibb, but BMS got two hugely successful drugs from the deal; if Medarex had remained independent, it could have become a $50B+ company.

A lot of it comes down to communication, and that’s another area where I think Genmab has excelled over other competitors, since we’ve found a way to be very honest and transparent with our shareholders, I think that’s the only way to stay independent.

Beyond that, the best protection for any company is a very high share price – and that we have done quite well over the last six years or so. When I stepped up to the CEO position in the summer of 2010, I refocused the company around a new strategy, and it has been working really, really well.

Images via extender_01, molekuul_be, vitstudio, Kateryna Kon, nobeastsofierce / shutterstock.com