The microbes living on our skin can play an important role in skin conditions such as acne. Philip talked to Veronika Oudova, CEO and co-founder of the Belgian company S-Biomedic, about how the company plans to fight acne with microbes, and the challenges of launching products in a field that is still unfamiliar to regulators.

Humans are colonized by over 10,000 species of bacteria, inhabiting places like the gut, mouth, and skin. Over the last decade, researchers have started to get glimpses of how the human microbiome can play a huge role in our health. “[The microbiome] is booming,” Oudova told Philip. “In 2004, there were around 600 publications about the microbiome, and in 2014 there were around 6000.”

In the skin cosmetics field, the microbiome hype is also taking off. However, many companies are offering cosmetic microbiome treatments without solid scientific evidence. “What you find, for example, is someone using a plant extract and claiming that it has an effect on the microbiome,” Oudova explained. “But we have not seen much data that would be solid enough to make that claim.”

One problem with collecting scientific evidence for cosmetic therapies based on microbiome science is that the field is very new, so researchers are not even sure what to measure. “You can take samples of the microbiome and read some changes, but what do they mean?” mused Oudova. This lack of knowledge makes it hard to design clinical trials.

S-Biomedic’s lead program focuses on the infamous skin condition acne. “Acne is one of the best described [skin conditions] in terms of the connection between the bacteria and the disease, so that was the easiest to start with,” said Oudova.

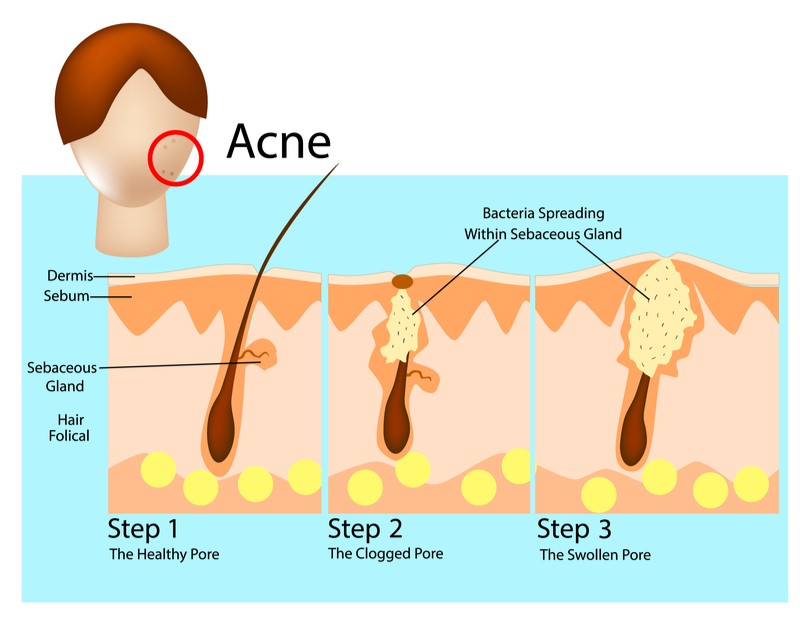

In acne, hair follicles get clogged with oil and dead skin cells, and a common species of skin bacteria called Propionibacterium acnes colonizes the blockage, causing inflammation. S-Biomedic’s therapy is designed to replace the acne-prone species of bacteria in the microbiome with more benign species, simply by applying a mix of the benign bacteria on the skin. “Our prototype should be completed in the next two years, and then will be tested in vivo,” explained Oudova.

However, getting approval for products in the microbiome field can be challenging. “There is a really big discussion going on between the FDA and EMA [about] how all these products should be handled,” Oudova reflected.

To circumvent this issue and speed up the launch, S-Biomedics plans to release the treatment as a consumer product, avoiding the clinical validation process required to have the product reimbursed by health systems. “In two or three years we could deliver [the product], instead of 5-10 years going through clinical validation,” explained Oudova.

S-Biomedic was founded in 2014 by Oudova, Marc Güell, and Bernhard Pätzold, now CSO, who was finishing his PhD and wanted to market the idea of modulating the skin microbiome. “It sounded so cool and promising and I said ‘OK cool, let’s give up my job and … jump into this crazy business,’” Oudava said.

The team collected its proof-of-concept data and technology patents at an accelerator program in Chile. It then relocated back to Europe to obtain funding, basing itself in the Johnson & Johnson innovation incubator JLABS in Beerse.

In July, S-Biomedic partnered up with the German skincare company behind Nivea skin creams, Beiersdorf, to complete the development of its acne treatment and commercialize it. “Sometimes we make the joke that it’s better to have two corporates than one,” said Oudova. “We are at the beginning of the collaboration but so far we are learning a lot.”

Having large corporate partners is essential for any startup to progress, but mutual benefits are biggest when you are a confident startup and stand up for yourself, said Oudova. That way the startup gains the experience of the larger partner, while at the same time contributing innovative techniques and methods.

With research into the skin microbiome starting to be translated into therapies, S-Biomedic, like others in the field — such as SkinBioTherapeutics in the UK or AOBiome in the US — faces the challenges of venturing into a new field where it is not clearly established how to design trials or get approval from regulatory agencies that are not familiar with these products. “Everyone in the field is an explorer,” says Oudova. The work of these pioneers is what will set the basis for the regulation of this new generation of products in the future.

Images from Shutterstock