Stay up-to-date with the latest news related to COVID-19. Subscribe to our newsletter.

Looking to expand your partner network with the latest in the field of COVID-19? Build relationships with academic teams and biotechs.

What is COVID-19?

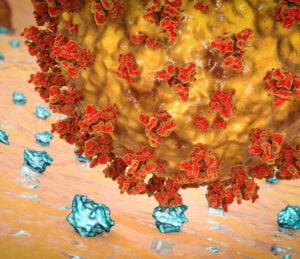

COVID-19 is an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus that emerged in Wuhan, China in late 2019 and has since become a global pandemic. It can cause a wide range of symptoms, primarily spreads through respiratory droplets, and can lead to severe illness and death, particularly in older adults and those with underlying health conditions.

How is biotechnology revolutionizing the treatment of COVID-19?

Biotechnology is revolutionizing the treatment of COVID-19 by providing innovative solutions such as vaccine development, diagnostic testing, novel therapies, large-scale manufacturing, and bioinformatics. Biotech companies are using cutting-edge technologies, such as mRNA and viral vector platforms, to develop vaccines and therapies, and their expertise in manufacturing to produce them quickly and efficiently. They are also using advanced computing and machine learning to analyze vast amounts of data and provide insights into the disease’s biology, transmission, and treatment.

Got a news story for us related to COVID-19? Send it to us here.