Update (01/10/2019): The scientists behind the study have declared that the results were based on erroneous data, meaning the mutation they studied has a weaker effect on mortality than initially reported.

A new study highlights the issues that can result from modifying human DNA without sufficient understanding of how it can impact our health.

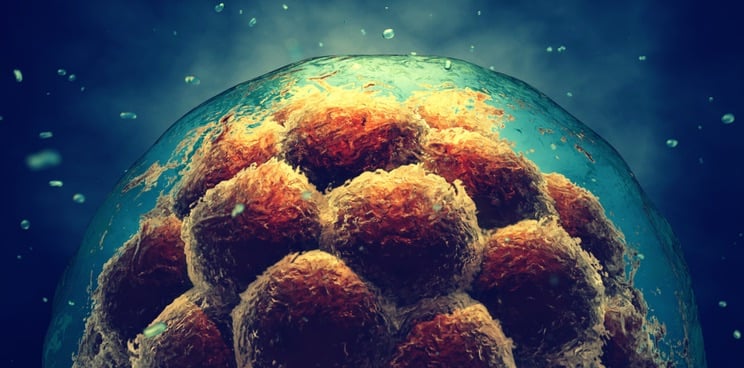

Last year, the scientific community was taken aback by the announcement of the birth of the first gene edited babies in China. The scientist behind it claims that the embryos were edited using CRISPR technology to introduce a mutation that protects against HIV infection.

The experiment has created a strong pushback because of the ethical implications of altering human DNA without fully understanding the possible consequences.

Today, the journal Nature Communications reported that people naturally carrying similar mutations have a mortality rate 21% higher than the rest of the population. Researchers from the University of California and the University of Copenhagen came to this conclusion by analyzing the DNA of over 400,000 British people stored at the UK Biobank.

The mutation introduced into the CRISPR babies affects a protein called CCR5 that is on the surface of immune cells and is used by the HIV virus as the entry point to infect human cells. The goal was to mimic a mutation in this protein called delta 32 that some Europeans carry naturally and confers resistance to HIV.

“Delta 32 is a celebrity mutation among evolutionary geneticists, and it is one of the most studied mutations,” April Wei, author of the study, told me. “There is a long controversy regarding whether the delta 32 mutation is beneficial or deleterious.”

Previous studies show that people carrying two copies of the mutation are four times more likely to be infected by the West Nile virus and are at higher risk of dying from influenza. (Only one of the CRISPR babies has been reported to carry two copies, which is necessary for full HIV protection.) Wei found that, while people with two copies have a higher mortality rate, those with only one copy — which are partially protected against HIV — were not affected.

She notes that the results are not directly applicable to the case of CRISPR babies. First, the data comes from people of British ancestry whereas the babies have an East Asian genetic background. In addition, the mutation might not be exactly the same.

“The CRISPR technology used does not guarantee the creation of the exact mutation it aims to mimic. Based on the information released about the CRISPR babies, they do have mutations on the same gene, but the mutations are different from delta 32,” explained Wei.

While the results don’t necessarily mean the CRISPR babies are at a higher risk of death, they highlight how important it is to conduct more research before performing these kinds of experiments in humans. This is especially relevant for those performed in embryos, as in those cases the genetic modifications can be passed onto the offspring.

“The technology is not yet ready to be applied to human embryos,” said Wei. “Before the CRISPR technology is ready, there should be more discussions about how to regulate its use among all the ethical concerns.”

“As was pointed out by our study, there are still a lot of things unknown about the functions of genes, including the phenotypes a mutation affects, and their functions in different genetic backgrounds and environments. For any editing, the consequences of all sorts need to be considered.”