Deconstructing patterns, the first exhibition of its kind at the Francis Crick Institute, is the result of months of collaborations between scientists and artists. I got a chance to see it at the opening earlier this week.

The new exhibition at the Francis Crick Institute puts into perspective the groundbreaking research happening in the scientists’ labs. Focused on the multiple patterns found at the microscopic level that make life possible, the exhibition is a collaboration between artists and the Crick’s scientists with the aim to bring science closer to any curious minds.

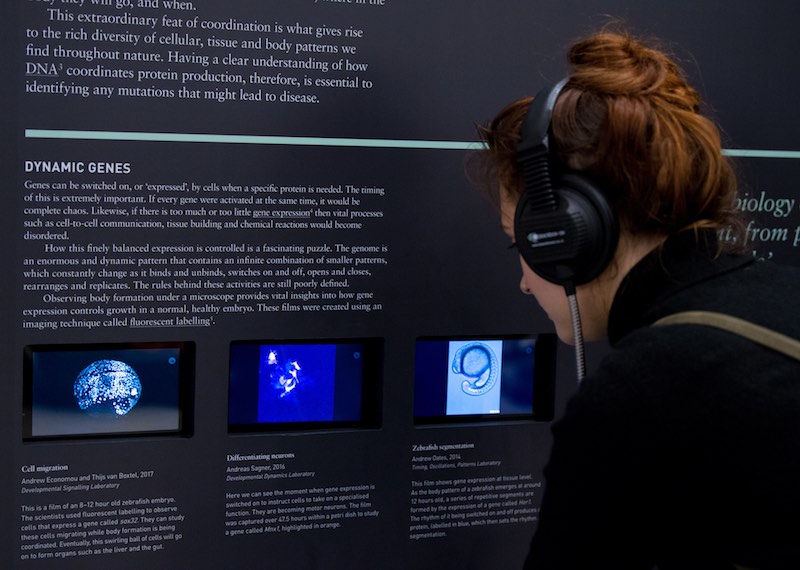

Deconstructing patterns makes state-of-the-art science — often only accessible through specialized journals — approachable to people of all backgrounds. Through images, sounds, videos, and written word, the exhibition showcases the exciting output of research that contributes to understanding illnesses like cancer, heart disease, stroke, infections, and neurodegenerative diseases.

As I entered the spacious room that hosts the exhibition, light shining through the building’s crystal walls, I could find the three main areas of the exhibition. Each of them highlights the research of one of the Crick’s groups along with a unique art piece specifically commissioned to artists that worked closely with the scientists.

The first immediately caught my attention. Four white pods hanging from the ceiling invite you to step in and listen, suddenly isolated from the rest of the world. In the smaller pods, one can hear a poem dedicated to the DNA by Sarah Howe, inspired by the work of the Advanced Sequencing facility at the Crick.

Stepping inside the bigger pods, four speakers talked to me at the same time. One for each of the subunits of DNA: G, T, C, A. The four fighting for my attention, making the ear tune to the voices among the noise, much like scientists look for patterns among vast amounts of DNA data. “My work brings a human perspective to the science,” told me Chu-Li Shewring, the sound artist behind the installation. “Sound goes a step beyond, acting as a metaphor.”

Stepping out, I could read about the Human Genome Project that sequenced our DNA for the first time. While it took 13 years and $3Bn to sequence that first genome, today we can do it in a matter of hours for $1,000 with a device that fits in a pocket. One genome alone can’t do much, but by comparing the genomes of patients and healthy people, scientists can better understand how diseases like cancer work. And there’s certainly beauty in that too.

The second station is centered on research of the development of the fruit fly’s eyes at the Visual Circuit Assembly Laboratory, run by Iris Salecker. Her work on the development of neurons that can transmit and process visual signals into the fruit fly’s brain offers an insight into neurological disorders in humans that stem from developmental defects.

After months of shadowing the researchers and getting hands-on at the lab, artist Helen Pynor built 3D models of the fruit fly’s optic lobe at different stages of development, photographed them, and put them at the center of a sculpture. The piece, hanging from the ceiling turns the science, strict and factual, into metaphors for the mystery that pushes our curiosity and for our search into the dark, much like neurons do during development.

“Transformations such as that of the fruit fly’s larvae are such a mystery,” told me Pynor. “As an artist, I bring in the bigger story, as well as the aesthetic and conceptual dimensions of science, resulting in a dialog with the humanities.”

At the end of the room a movie played on repeat brought the basic rules behind the development of complex organisms from biology to the daily life of a Londoner. The film makers were a group of teenagers that based their work on what they learned during a one-day workshop at the Polarity and Patterning Networks Laboratory.

Run by Nate Goehring, the lab seeks to understand how molecular patterns within cells determine the creation of all types of organisms, from the worms studied at the research group to ourselves. The researchers study how a series of rules programmed into molecules can lead a first perfectly symmetric cell to create a full organism, by breaking that symmetry and creating multiple different cell types where there used to be only one.

“The exhibition brought up how to get the message across as a scientist,” told me Goehring about his work with the young film makers. “It forces you to step back and deconstruct your science to the core concept.”

That seems, indeed, to be the core idea of Deconstructing patterns. Taking the science beyond the jargon and making it accessible to people of all backgrounds through art, video, images, and sound.

Deconstructing patterns will be on show at the Francis Crick Institute until December 1st, 2018.

All picture credits to Fiona Hanson © Copyright 2018 ; Francis Crick Institute. Deconstructing Patterns.