Jellyfish are a source of collagen: this is the idea behind the winner of Boost Cymru, a competition of the Life Sciences Hub Wales. We had a chat with Andrew Mearns-Spragg, CEO of Jellagen, about this promising startup.

![]() The jellyfish already has a place in Biotech’s hall of fame as the source of the gene for the green fluorescent protein (GFP), which is essential in biological research. However, as fascinating as these creatures are (see the work of bioartist Robertina Šebjanič), they are hardly seen as economically relevant.

The jellyfish already has a place in Biotech’s hall of fame as the source of the gene for the green fluorescent protein (GFP), which is essential in biological research. However, as fascinating as these creatures are (see the work of bioartist Robertina Šebjanič), they are hardly seen as economically relevant.

In fact, they are often regarded as a nuisance, and recent extreme rises in jellyfish populations have even been dubbed ‘Jellymageddon‘. But Biotech could be on track to harness some of their interesting properties.

“The idea of using jellyfish was something that I had in the back of my mind for a number of years,” says Andrew Mearns-Spragg, CEO of Jellagen. He is a marine biotechnologist with years of experience in this branch of Biotech. He founded Jellagen in 2013 to investigate jellyfish as a source of collagen.

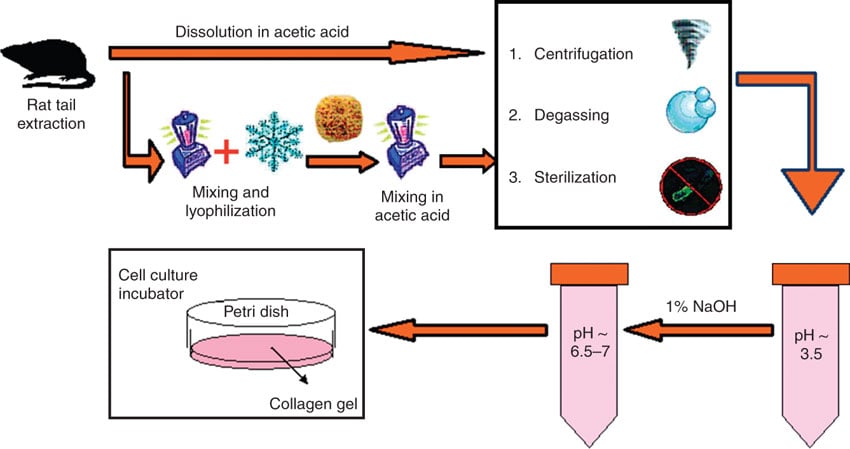

He noticed that “there was a need for safer alternatives in the collagen market“. Collagen is a protein with a lot of applications, and there is a well-established market providing collagen extracted from cows, pigs, fish and even rat’s tails. But for one of the most promising applications of collagen, as biomaterials for medical applications, the current sources of collagen can pose a challenge with safety and compatibility.

Jellyfish collagen carries less risk of prion and viral contamination than the usual sources. Moreover, it has the potential to be a more “universal” biomaterial for different applications like 3D cell cultures for tissue engineering.

As Spragg explained, the most widely used collagen on the market, Type I, is applied to research and medicine. Type I Collagen is a fibrillar collagen found predominately in connective tissues such as skin and bone. However, as humans are able to culture a wider range of cell types, these may require different types of collagen that are usually prohibitively expensive to translate into research and clinical applications.

The use of this type of collagen in these tissue cultures is therefore limited; they may require type II collagen, one of the many types of mammal collagen. However, specific collagen types can be very expensive, limiting its use. “Because jellyfish are so ancient, their collagen isn’t type I or type II, but a much earlier template in the evolutionary scale,” Spragg explained. As such, it can work with a wider range of cell types.

To explore this interesting collagen, Spragg went on to found Jellagen in 2013, based in Cardiff, Wales. The young company succeeded in extracting and purifying collagen from jellyfish, and it is already selling its products to research labs. Due to its advantages, “

Due to its advantages, “jellyfish collagen has the potential to go from a Petri dish to a medical application. Of course, developing our material for medical applications will require achieving medical grade status for our collagen; this, in turn, requires reaching cGMP for our manufacturing process. We are currently working towards cGMP and building a manufacturing facility in Cardiff. This is the stage we’re at right now”, said Spragg.

So far, Jellagen has managed to attract £2M in funding from grants and angel investors. And it has just won the Boost Cymru competition for innovation in life sciences, hosted by the Life Sciences Hub Wales, and sponsored by well-known names like Microsoft and MSD.

Using jellyfish struck me as similar approach to that of Ynsect, an insect biorefinery: both use animals that are abundant, but not so commonly farmed or fished. Could Jellagen extend its jellyfish expertise to other products?

“There are some other products in there that we are interested in, but right now we are focused on getting our collagen on the market“, answered Spragg. Even for collagen, he says “we are building a new market“. Jellagen is the first of its kind in Europe, though there are a few other companies into jellyfish collagen – Agam in Israel, and an initiative in Japan.

What about the overall market for collagen? In a handful of years, could jellyfish overtake not only medical niches, but also be in face creams and other more mundane products? Spragg reiterated that Jellagen is very focused on its priority, the higher end of research and biomedical applications, “but yes, there’s the ambition that this could be disruptive”.

Images via borzywoj/shutterstock.com; Rajan et al. (2007) Preparation of ready-to-use, storable and reconstituted type I collagen from rat tail tendon for tissue engineering applications. Nature Protocols (doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.430)