Karen Aiach had no background in science or the biotech industry, yet when her daughter Ornella was diagnosed with the super-rare Sanfilippo syndrome this inspired her to co-found and become the CEO of Lysogene, today a clinical-stage biotech based in Paris, France.

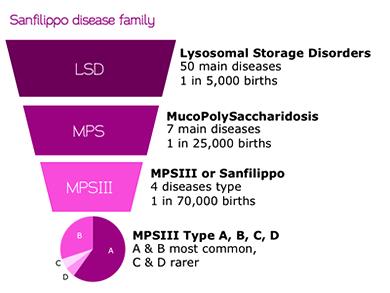

Now Ornella is participating in the ongoing clinical trials for a new gene therapy for Sanfilippo A, also known as mucopolysaccharidosis III (MPS-III). A disease for which currently there is only palliative care available. there are 4 types of MPS-III, and their combined incidence is only 1 of every 70,000 births. A genetic mutation in a particular enzyme causes toxic build-up of heparin sulfates, which cause permanent tissue damage and paralysis.

Akin to the famous John Crowley — another Biotech entrepreneur inspired by his children’s diagnosis with a rare disease — Karen’s fight is indeed personal. Her inspiring story has led to phase I/II clinical trials for a new gene therapy for Sanfilippo syndrome A, in which her daughter is one of the patients enrolled.

I met him in 2005, pretty rapidly after having the diagnosis of Sanfilippo for my daughter. As this is such a rare disease, patients and doctors can interact relatively easily, and a few months after this diagnosis a friend of mine recommended his expertise in the field.

He was a leading scientist in the field and a scientific director at Genethon, which he left in 2011. I was actually searching for someone of really high quality in neurodegenerative disease who would be able to help with my daughter’s condition.

Now, Olivier has founded the company with me and acted as the Senior scientific advisor — not as an employee but a proper shareholder of the company.

So, Olivier brought the scientific technology to the company?

Yes. Basically, when I made the decision to launch a gene therapy program for Sanfilippo, they were already debating transferring recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors into the brain of animals with MPS.

So, it was pretty clear we also wanted to use an AAV vector, but I think we were really audacious in making the choice to use the AAVrH10 virus, in contrast to our French colleagues at the Pasteur Institute who were using an AAVrH5 variant.

This was our key area of innovation, since by selecting the AAVrH10 vector we had a much greater transfection profile for the brain and therefore better chance of uptake of the gene therapy].

How does the injection procedure work?

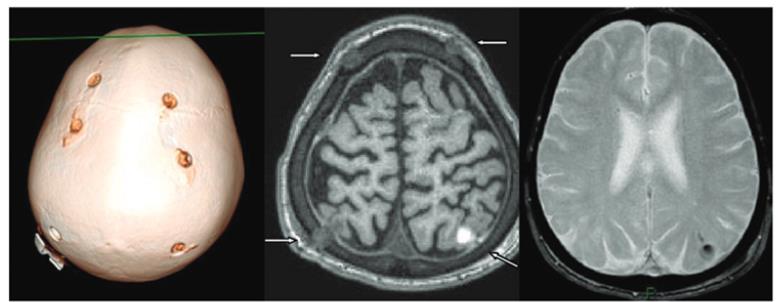

Making micro-bore holes into skull, the vector is delivered via intra-cranial injection directly into the white matter of the brain. Micro-catheters were inserted into the 6 bore holes which were made in the first study, to access 12 different injection sites.

This surgical technique was originally developed in New York and is now by far the one with the most data for AAV delivery backing it so far, not to mention a robust safety profile.

Comment: This technique has also been used to treat other Lysosomal storage diseases (e.g. Batten’s, Canavan etc.) as well as other CNS diseases like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. Thus, despite the procedure sounding slightly horrific, it is, in fact, a relatively robust method of vector delivery, being used since the early 1990’s.

Pretty amazing Medicine can do this today, huh.

So do you already have products on the market using this procedure?

No, not yet. Currently our leading candidate is the rAAVrH10 delivery of a N-sulfoglucosamine sulfohydrolase enzyme, which breaks down excess sulfates and therefore alleviates tissue damage. Recently this enzyme replacement therapy completed its phase I/II study with four children, three of them aged six and 1 three years old.

six-year-oldsolds had already a fairly advanced stage of Sanfilippo. Results showed good tolerability and encouraging efficacy profiles, and was published in Human Gene Therapy in June last year.

However, the most impressive result of these investigational therapy trials, was that these patients improved their behavioral patterns and sleep (some key adverse symptoms caused by of Sanfilippo). On the other hand, with respect to general testing of cognition we could not prove any more indication [of the therapy] in the older children, as their cognition was too impaired at the time of enrollment.

There is a long term follow up study going on at the moment, and we’ve not published the results yet.

Were you required to have a placebo for this study?

No. The next study of Lysogene will start in early 2017, enrolling up to 20 patients granted we get approval — so we’re currently in discussion with the European Medicines Agency. However, as is the case with rare diseases, we absolutely cannot use a placebo (given the nature of the trials with children and the use of neurosurgery).

We hope to aim for marketing approval around 2020.

Comment: A rare disease is given a different approach regarding clinical trials, considering the scarcity of patients and the severity of symptoms (and particularly given the risk of undergoing Neurosurgery without the chance of benefiting from the therapy). Genzyme was a game-changer for rare disease in the early 80’s, prior to which clinical trials simply didn’t go ahead…

How many patients has Sanfilippo (MPS-III) worldwide?

Around 3000 individuals are diagnosed as of today, but often as is the case with rare diseases, many patients remain un-diagnosed.

For our next trial, we will have multiple sites around the World, both in the US and in Europe; including the Netherlands (Amsterdam Medical Centre) and our existing sites in France.

How was becoming a for-profit company perceived?

The reason why we went on to become a profit organisation, is because we needed to raise a big amount of money for trials, and it’s not easy to do this in a non-for-profit setting. When it’s about raising millions of euros, you need to have something to attract investors with.

I myself graduated in business and started a career in a private company, so it helped the business side of founding Lysogene.

One last question; I saw the movie about John Crowley. How inspiring was his story to you?

It was extremely inspiring. He was one of the very first people I met with. I have a very powerful memory of my first meeting with John and it was really an honor for me. He took the time to talk properly with me, even if he is now Senior Vice President in New Jersey.

John Crowley is another such Biotech figure, famous for his founding of Orexigen Therapeutics after 2 of his children were diagnosed with Glycogen storage disease type II (also known as Pompe’s Disease). In a management role at Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crowley also came from a non-scientific background, but was inspired to start Biotech to help his children. Since then a book and film (Extraordinary Measures) have been made about his story.

It was a pleasure to speak with Karen. And what is particularly impressive in her case, is that instead of pursuing a non-profit stab in the dark at fighting such a disease, she really used her business acumen to build a sustainable plan to tackle Sanfilippo syndrome. Evidently the barriers to biotech are not as intimidating as they appear, and anyone has the potential to make major leaps in the field, regardless of their academic background.

So, despite promising results from these trials, the next 5 years will prove crucial to Lysogene’s long-term plan for market approval.