Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

After CRISPR, there’s a new genetic technique with a tongue-in-cheek name in town: LASSO cloning.

Researchers from four institutions, including the US-based John Hopkins, Rutgers and Harvard, and the University of Trento in Italy, have developed a new technology to study large chunks of DNA and their function. The work behind it was recently published in Nature Biomedical Engineering, and a patent was filed earlier this month.

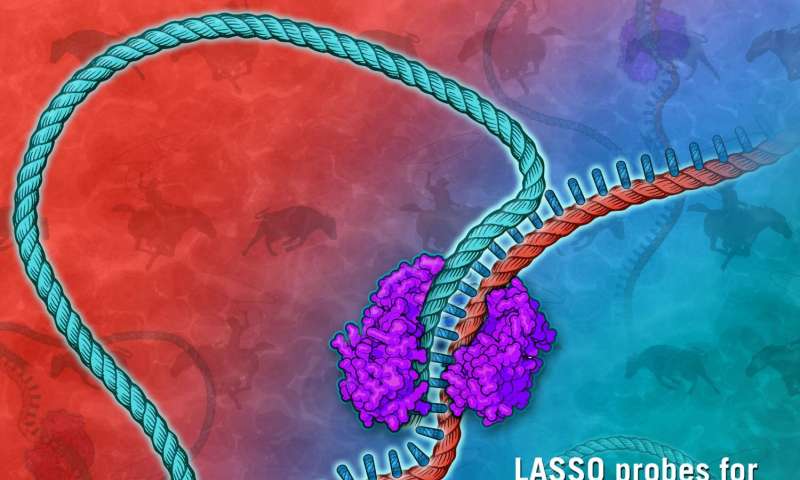

This molecular tool is called long adapter single-stranded oligonucleotide, or LASSO for short. The lasso rope metaphor applies to the tool’s mechanism, which can “capture” and clone long sequences of DNA fragments. Fragment length had so far been the main challenge for cloning probes and the genome sequencing field at large. Next generation sequencing (NGS), which has gained a lot of attention in medical research, relies on sequencing short fragments that are then put together, like a puzzle, by bioinformatics tools. However, this method falls short for certain types of samples. Short reads capture only about 100 base pairs, or DNA “letters”, at a time, while LASSO can read more than 1000 base pairs.

As a proof of concept, the researchers set out to test LASSO probes in biotech’s favorite microorganism, E. coli. The tool managed to simultaneously clone over 3000 DNA fragments of the genome of E. coli, capturing around 75% of the targets and leaving almost all of the non-targeted DNA alone, and the study’s authors say there’s still certainly room for improvement.

LASSO cloning should enable the scientific community to build libraries of a given organism’s protein in a much faster and cheaper way, democratizing research that was so far only within the reach of big research consortia. The usefulness of such studies ranges from a better understanding of organisms to the ability to screen large libraries of natural enzymes and compounds that could be valuable leads in drug discovery, as it has been done before for some species like Penicillium fungi strains, for example.

One of the organisms to be better studied is, of course, human beings. Researchers already tested LASSO cloning with human DNA, something has the potential to yield new biomarkers for a range of diseases. Another focus of interest is the human microbiome. As described in the same paper, LASSO was used to build the first protein library of the microbiome, and the research team hopes that it can improve precision medicine strategies that take into account the microbes living within us.

Images by DWilliam/Pixabay and Jennifer E. Fairman/John Hopkins University