The first paper on CRISPR gene editing tech was only published in 2012. As a key player in the biotech revolution, CRISPR is the discovery of the century, permitting a whole new field of gene-editing for therapeutic purposes in a range of different research areas.

Two of  those responsible for the existence of CRISPR-Cas9, Jennifer Doudna from UC Berkeley and Emmanuelle Charpentier, now based in Berlin at the Max Planck Institute, have surprisingly not won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, despite Reuter’s prediction.

those responsible for the existence of CRISPR-Cas9, Jennifer Doudna from UC Berkeley and Emmanuelle Charpentier, now based in Berlin at the Max Planck Institute, have surprisingly not won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry, despite Reuter’s prediction.

The categorization of Nobel Prizes has often been slightly blurred, with many key biomedical discoveries also being awarded the Chemistry prize. The announcement for the prize in Chemistry comes just two days after the joint-award for the Nobel prize in Medicine & Physiology, which went to the discoverers of ivermectin and artemisinin, two medicines for parasitic diseases.

But the prize has gone instead to Thomas Lindahl, Paul Modrich and Aziz Sancar for their DNA repair mechanism discoveries at the Francis Crick and Karolinska institutes.

The significance of CRISPR to scientific research has already been recognized by multiple prestigious award institutions, having received the wannabe ‘Spanish Nobel Prize’ equivalent in May this year. Doudna & Charpentier were also recipients of the $3M ‘Breakthrough Prize‘ — the American attempt at Nobel Prizes backed by founders of Alibaba, Facebook and Google.

We’re therefore very surprised that 2015 wasn’t also the year for the legit Nobel prize award to be added to their growing display cabinet. But fear not, it’s bound to happen sooner or later…

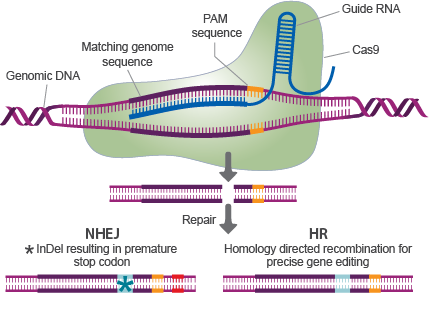

CRISPR, which stands for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” functions as a gene editing system derived from a prokaryotic mechanism of gene-interference.

Derived from short repeats of prokaryotic DNA, the system exploits the tendency of bacteria and archaea to insert short sections of DNA, called spacers, into their genome, in order to acquire immunity to certain pathogens and abiotic stresses.

Charpentier and Doudna found that a simple CRISPR system used the nuclease (gene-cutting) Cas9, which could be manipulated to edit specific genes. The first paper demonstrating this CRISPR-Cas9 technique for gene-editing in humans was only published in 2012 in Science.

CRISPR sequences were actually first noticed in 1987 by Yoshizumi Ishino working with Escherichia coli, and several research groups hypothesized the possible therapeutic applications of using CRISPR in medicine shortly after.

However, since Doudna & Charpentier et al. proved its manipulation with Cas9 in vivo first, a heated patent war in the biotech industry has arisen as a result.

Now the CRISPR-Cas9 patent is out there being exploited by various clinical R&D biotechs. For example, t

So even though this is Biotech history in the making, CRISPR – one of the most talked about gene-editing tools in the Biotech industry will have to wait another year for a Nobel prize.