Gene therapies for the rare blood clotting disorder hemophilia B have taken a step closer to the market as Dutch developer uniQure became the first to release interim phase III results last week.

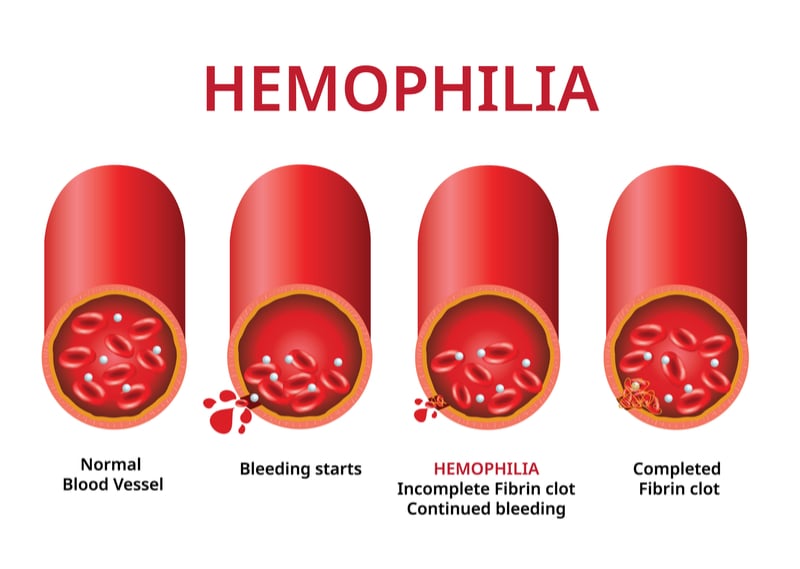

Hemophilia is an inherited disease caused by mutations to genes encoding blood clotting proteins, resulting in uncontrollable bleeds. In severe cases of hemophilia B — the second most common type of hemophilia — blood levels of the protein clotting factor IX (FIX) can reach less than 1% of normal levels. While patients can be injected with donor or synthetic FIX, this therapy requires frequent injections. However, gene therapies could solve this problem by restoring the patient’s ability to produce FIX with one injection.

Shares in uniQure surged about 10% last week as its phase III-stage gene therapy for hemophilia B showed the potential to become the first of its kind to reach the market. According to results from 54 patients, FIX levels had risen from less than 2% of what is considered normal to a mean of 37.2%, six months after dosing. Additionally, no serious adverse effects were reported and the need for standard FIX replacement therapy went down by 96% compared to before the injection.

uniQure’s gene therapy is introduced into the liver by a viral vector carrying genetic instructions for the making of FIX. In June, the company sold the global rights to the therapy to CSL Behring for up to €1.8B.

“There are many innovative therapies being investigated in hemophilia currently, but without a doubt gene therapy is the most cutting edge and the one therapy that can be truly transformative, taking patients from having the day to day worries and anxieties of bleeding and the regular intravenous or subcutaneous therapies they need to prevent bleeding to a state of full normalcy,” Guy Young, a hemophilia expert at the Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, US, told me.

“[uniQure’s] treatment was shown to be safe at least in the short term and exceptionally effective at preventing bleeding and reducing [FIX] consumption.”

The UK biotech Freeline Therapeutics and a partnership between Pfizer and Spark Therapeutics in the US are uniQure’s closest competitors in the gene therapy niche and are preparing their own phase III studies. Although uniQure’s therapy has been tweaked to boost its effects over the last few years, these rivals look to better uniQure’s results.

“The normal range of FIX activity is 50-150%,” Julie Krop, Freeline’s CMO, told me.“While uniQure has demonstrated the ability to obtain mean values of FIX activity in the mild hemophilia range — around 37% — it is still not creating a true functional cure.” By comparison, she added that some patients in Freeline’s trials had a mean of 98% FIX activity six months after dosing.

Many unknowns, however, remain. An overly steep increase of FIX, for example, can be dangerous as it can lead to thrombosis and strokes — this is one potential side effect of gene therapy for hemophilia B, which has already popped up in a clinical trial run by Freeline. It’s also a significant side effect of more conventional treatments.

uniQure also claims its gene therapy overcomes a common snag in gene therapy: the immune system of patients destroying gene therapies before they take effect. This happens when the body recognizes the viruses used to carry the gene, and has antibodies ready to neutralize them. uniQure’s therapy appeared to work even in people with these antibodies albeit with the exception of one whose antibody levels were unusually high.

“The ability to dose a gene therapy in patients with pre-existing neutralizing antibodies has not been demonstrated for any other gene therapy and illustrates the potentially unique ability of our platform to address the needs of a broad set of patients living with hemophilia B and other disorders,” said Ricardo Dolmetsch, President of Research and Development at uniQure, in a public statement.

Hemophilia has been in the crosshairs of numerous biotech companies in recent years. Treatments in the pipeline include gene and cell therapies such as uniQure’s, but also RNA interference (RNAi) treatments such as Sanofi’s fitusiran that prevent the formation of the anti-clotting protein antithrombin. A wide array of antibodies that target various stages of the clotting process are also being developed, from those that block anticoagulants such as Novo Nordisk’s concizumab and Pfizer’s marstacimab to those that mimic the activity of clotting proteins such as Roche’s emicizumab.

Gene therapies are also a hot topic in the treatment of hemophilia A, the most common form of the condition. Last summer, the FDA rejected the approval of a hemophilia A gene therapy developed by the US frontrunner, BioMarin. Meanwhile, other candidates in phase III include one developed by a team-up of US giants Pfizer and Sangamo and another by Roche, which acquired the US gene therapy specialist Spark Therapeutics last year.

As gene therapies for hemophilia edge closer to the market, questions remain over their price tag. Approved gene therapies sometimes cost hundreds of thousands of dollars for a single course. If hemophilia gene therapies have similarly daunting prices, this could limit access of patients to the treatments in the foreseeable future, even once the products hit the market.

“The key obstacles for gene therapy for hemophilia B include long-term safety concerns for this new platform for which answers will only come years into the future, concerns about the patient to patient variability in response, and once a product is available, the cost,” Young added. “It should also be noted that gene therapy trials for now only include adults such that children, arguably the group that has the most to benefit from early treatment with gene therapy, cannot participate.”

Image from Elena Resko and Shutterstock