Western culture seems to revolve exclusively around humans. It seems that we have forgotten the existence and the needs of all other organisms, from microscopic bacteria and fungi that make our food and medicines to the chickens and cows that feed us.

But is this anthropocentric behavior justified? What are the consequences of our destructive attitude towards nature? Could we learn something by trying to see the world from the point of view of other living beings?

Scientists, artists and philosophers gathered last month in Berlin to discuss these and many more questions about the anthropocentrism that dominates Western culture. I joined them at the interdisciplinary conference Nonhuman Agents in Art, Culture and Theory, organized by Art Laboratory Berlin, to learn first hand how such different disciplines can come together to challenge the way we think of and treat our environment.

The talks and discussions that ensued during the three conference days revealed a growing community of people from all sorts of backgrounds that are challenging our anthropocentric worldview — by shifting the focus from humans to the organisms that share our planet, exploring how they perceive or interact with the environment and us, humans.

Artist Heather Barnett explores these relationships through her own relationship with a microorganism called Physarum polycephalum, most commonly known as slime mold. Barnett has been creating art in collaboration with this bright yellow microorganism for the past 10 years.

Her work includes time-lapse videos of how the slime mold grows and moves in different conditions, as well as choreographies and workshops where people attempt to enact slime mold behaviors. They explore the unique collective intelligence of this fascinating creature, which is able to orient itself in space, remember where it has been before, and find the shortest path to its destination without having a brain. Through her art, Barnett invites us to reflect on the existence of many other forms of intelligence other than our own.

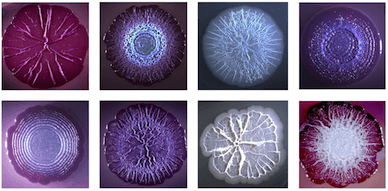

From the academic research front, Regine Hengge presented her work on biofilms, which she carries out at Humboldt University Berlin. These are structures formed by bacteria that she finds similar to how our own cells behave to form tissues. In biofilms, bacteria of the same species take on different roles and tasks that allow them to form complex structures.

These biofilms are essential for applications from food production to wastewater management. However, they can also be responsible for caries, chronic infections and clogging of industrial pipes. Her research aims to find out how genetics and the environment affect biofilm formation, ultimately getting an insight into the complexities of seemingly simple forms of life. I thought her experiments were almost artistic, resulting in mesmerizingly aesthetic bacterial structures.

Bacteria are also at the heart of the work of Anna Dumitriu, a British artist that declares herself obsessed with the concept of antimicrobial resistance. The ability of pathogenic bacteria to develop resistance against the drugs we use to fight them is a massive threat to humans, expected to claim more lives than cancer by 2050.

Dumitriu’s art incorporates pathogenic and antibiotic-resistant bacteria, some of which have been genetically modified by the artist herself using CRISPR technology. Some of her pieces are The Antibiotic Resistance Quilt, which sends a message of both warning and hope for the future regarding antimicrobial resistance; and Make Do and Mend, an homage to the history of antibiotics since their discovery 75 years ago.

But our view of bacteria solely as a threat is quite anthropocentric. Anna Dumitriu reflected that, with the development and sometimes indiscriminate use of antibiotics, we have also in a way “damaged” these bacteria and forced them to carry these resistance genes that are today essential for their own survival.

Indeed, we are not just damaging bacteria, but essentially almost every species living on Earth today. David Sepkoski, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, is dedicated to studying the “sixth mass extinction” that might be underway. Although he admits that it’s difficult to quantify how big the damage is, it seems quite clear that we humans are behind the extinction of many species that scientists have been observing in the past years.

At the same time, he sees the way we talk about this possible mass extinction as “extremely pretentious” and anthropocentric. We’re putting ourselves at the center, as the only force behind the problem, while it’s rather a combined result of our own activity and that of many other organisms, such as cows producing greenhouse gases, fungi killing chestnut trees in the UK or the Norway rat causing extinctions when it arrived to Asia.

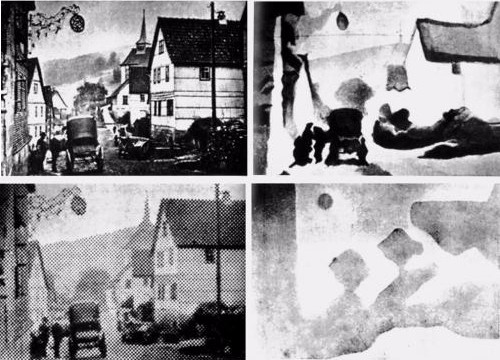

But art and science can also be used to fight our fast destruction of the environment. Birgit Schneider, Professor of Media Ecology at the University of Potsdam, studies how media can be used to get closer to other organisms by exploring how they perceive the world. These efforts started in the early 20s with Jakob von Uexküll, who coined the term umwelt, used to refer to different perceptions of the same environment by different organisms.

New media technologies have recently allowed us to explore the concept further. For example, the project In the Eyes of the Animal uses virtual reality to let people experience how differently a mosquito, a dragonfly, a frog and an owl perceive the same forest. Virtual reality has also been used for animal activism campaigns given the possibilities it opens to create empathy.

Artist Austin Stewart, however, has taken it further and designed a VR headset for chickens, raising questions around what would chicken like to see, but also offering an ominous view into a future where this technology could be used to enclose animals in ever smaller compartments while making them believe they are outside.

These and many more talks, ranging from the origins of life to art made with mushroom mycelia, sparked curiosity and multiple debates regarding how we view and treat other organisms. I found it refreshing to see scientists and artists alike come together, step out of their comfort zone and be open to bringing new perspectives to their work.

Images via Heather Barnett; Art Laboratory Berlin; Regine Hengge; Anna Dumitriu; Austin Stewart