Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Among other measures, the new policy changes the way companies are reimbursed for antimicrobial drugs, which is expected to increase investment in biotech and the interest of big pharma in tackling antimicrobial resistance.

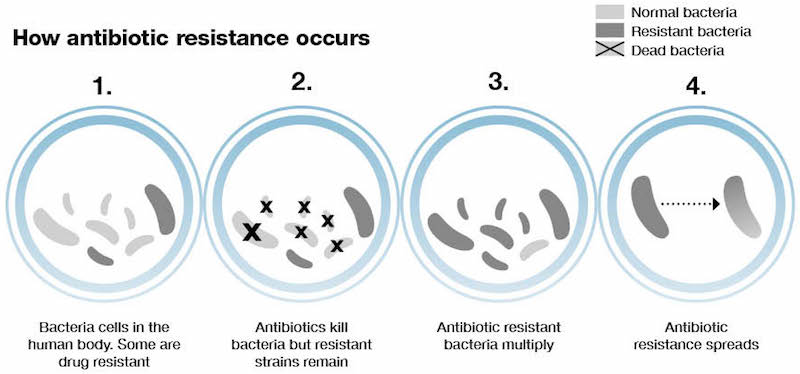

Antimicrobial resistance is a huge problem. More and more pathogens are becoming resistant to antibiotics, as seen in the rising number of cases where none of the existing drugs were able to end an infection.

These ‘superbugs’ are expected to kill 10 million people by 2050. “That’s many more than the combined global death toll of cancer and diabetes put together,” Bill Love, CSO of the British company Destiny Pharma, told me. “Many hospitals don’t actually record the bacteria and their resistance profile, so that number is an underestimation in my view.”

Tackling antibiotic-resistant S. aureus infections, Destiny Pharma is one of many companies working in the antimicrobial resistance field that will likely benefit from the new policy laid out by the UK government last week. Among the measures for preventing and dealing with antimicrobial resistance, the 5-year plan addresses a core problem in the development of antimicrobials that has led major pharmaceutical companies to abandon the development of new antibiotics.

“This has been a problem for decades with anti-infectives. Pharma has focused on oncology or chronic conditions, where there is more money to be made and higher margins,” said Love.

“The drive to develop novel antibacterials has been impacted by the potential returns, which are generally lower than for drugs in other therapeutic areas, such as cancer, where drugs are taken for years rather than very short courses,” said Heather Fairhead, CEO of Phico Therapeutics, a Cambridge-based company developing antimicrobials that target bacterial DNA.

The new policy establishes that companies will be paid for antimicrobial drugs based on how valuable they are to the UK’s National Health Service rather than on how many are sold. This can make a big difference for drugs that are meant to only be used as a last resort in those cases where conventional antibiotics don’t prove effective.

This decision can have a big impact on biotech companies working on the development of new antimicrobials. “The announcement itself could start to have an impact on biotech companies being able to raise funds to start, or continue, developing these drugs,” said Fairhead.

“In what appears to be a Zeitgeist of increasing appetite for acquisitions, support of biotech companies through this policy may translate into a rich vein of potential licensing deals with and acquisitions of innovative biotechs by big pharma to boost their pipelines,” said Graham Dixon, CEO of Neem Biotech, a Welsh company seeking to treat chronic infections with an antimicrobial compound found in garlic.

The UK is one of the first to put into practice policies that have been discussed on a global scale for several years as the threat of antimicrobial resistance becomes evident. “If this trial is successful then it could have global implications for reimbursement of antibacterials,” added Fairhead. “The UK’s approach could pave the way for other governments to implement similar strategies.”

Fortunately, it seems like the situation is starting to change. The number of initiatives funding research into antimicrobial resistance are multiplying and growing. The international CARB-X hub has pledged €440M ($500M) to the cause, while last year Novo Holdings created a €135M fund dedicated to antimicrobial resistance research.

While researching new variants of traditional antibiotics is an important part of keeping up with antibiotic-resistant pathogens, biotech companies like Destiny Pharma, Phico Therapeutics and Neem Biotech are working towards the development of brand new alternatives that could help the cause in the long term.

“We are always going to need new antimicrobial drugs, it’s a wrestling game with evolution and bacteria are going to overcome new drug mechanisms,” said Love. “We believe in developing new antimicrobials that can maintain long term effectiveness because the way they are designed makes it very difficult for bacteria to become resistant to them.”

It remains to be seen how well the UK’s new plan will pan out. “Any change for the biotech sector as a result of this policy is likely to depend on how well the sector can maintain the momentum that it has been building over the past 12 months… It will also depend on how quickly this policy allows access to the necessary financial resources,” said Dixon.

“What is certain is that the potential impact of antimicrobial resistance may well outstrip the resources available to deal with it if a case of “business as usual” were to persist.”

Images via Shutterstock; Gov.uk