Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Genfit is poised to become the first company to get a treatment for NASH to market — something that could happen as early as 2020, should its late 2019 phase III trial results be positive. I spoke to Dean Hum, the current COO and CSO of Genfit, to find out more about the company’s 20-year journey and its hopes for the future.

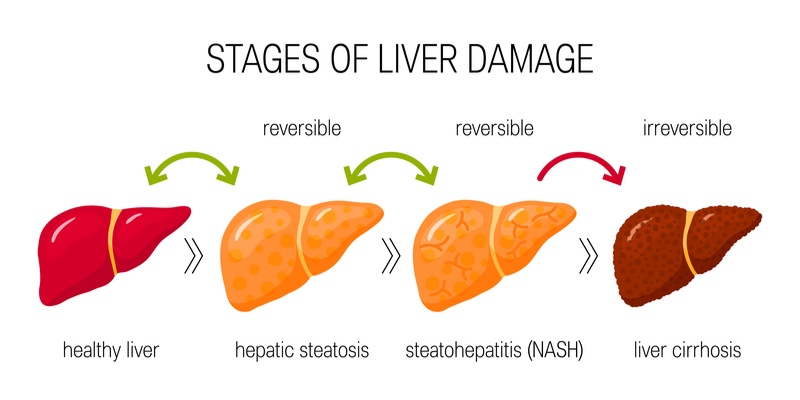

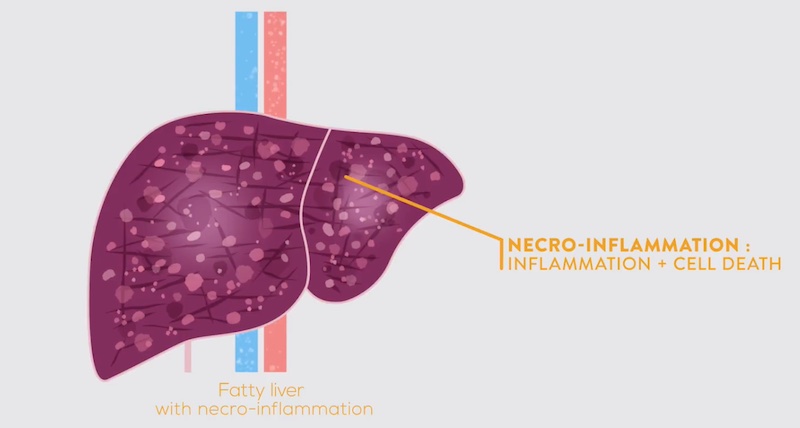

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, is a silent but severe liver disease, affecting up to 12% of adults in developed countries. Linked to the rise in obesity and type 2 diabetes, it is an increasing health problem and one of the leading causes of liver transplantation.

Despite the size of the problem, there are currently no approved therapies for the condition. The French biotech Genfit is a longstanding contender to get the first approval crown with its late-stage drug candidate elafibranor.

The company started down this road in 2011–2012 when they realized that the best indications for the early stage drug were in treating NASH or cardiovascular disease.

“At that time, realizing the unmet need in NASH and how that landscape was shaping up… we knew that we were going to be able to work together with the experts, and the FDA and the EMA, to move the field forward. This is how we got into NASH, which was at that time a big decision,” said Hum.

He explained that when Genfit made this decision 7 years ago, there were only a few other companies developing possible treatments for NASH, a number that has now expanded to over 50. “Within that landscape, I think it’s important to realize there’s only a handful of late-stage phase III programs,” he noted, citing Gilead, Intercept, Allergan and Madrigal as Genfit’s key competitors to be first to the market.

He explained that when Genfit made this decision 7 years ago, there were only a few other companies developing possible treatments for NASH, a number that has now expanded to over 50. “Within that landscape, I think it’s important to realize there’s only a handful of late-stage phase III programs,” he noted, citing Gilead, Intercept, Allergan and Madrigal as Genfit’s key competitors to be first to the market.

Developing an effective therapy for NASH has proved tricky with a number of high profile trials failing at a late stage. Genfit’s position as frontrunner has become a lot more promising since Gilead’s anti-fibrosis drug selonsertib failed at phase III in two trials and Intercept’s phase III trial of its anti-fibrosis drug Ocaliva had inconclusive results, both earlier this year. Allergan and Madrigal are also testing drug candidates at phase III, but are currently behind Genfit, which is expecting phase III results at the end of the year.

Despite the problems experienced by other late-stage contenders in this space and indeed the debated success of Genfit’s own phase II study of elafibranor in NASH in 2015, Hum seems to be confident that the drug will not disappoint in December.

“It’s a very aggressive timeline, but we’re going to work hard to make that happen,” emphasized Hum.

“What’s important when you look at late-stage phase III programs is the timing advantage. What our commercialization team is teaching us is that in such a large indication, having that… advantage is going to be huge. Any of these following programs that get on the market are going to have to show something that’s substantially different and advantageous if they hope to get any part of the market share.”

Genfit’s recent €139M Nasdaq IPO suggests that a decent number of investors also believe in the promise of elafibranor, a dual PPAR alpha and delta agonist. Elafibranor acts to resolve the build up of toxic fats in the liver seen in NASH and has the potential to treat other conditions as well. For example, the company is currently testing it as a treatment for the rare liver autoimmune disease primary biliary cholangitis.

PPARs are a family of proteins that impact how genes are expressed, particularly relating to metabolism. Different types of PPAR-targeting drugs have been used to tackle high blood sugar and fat in the past, for example in type 2 diabetes.

Given this history, Genfit has not been the only one to test PPAR agonists for treatment of NASH. However, the results so far have not been promising. In June, US-based Cymabay released interim phase II results from its trial of seladelpar, a PPAR delta agonist, showing it was less effective than placebo at reducing liver fat content.

Despite this, Hum is not worried by Cymabay’s results and believes that the dual action of elafibranor is key to its success. He says evidence suggests that activation of both PPAR alpha and delta, as opposed to PPAR delta alone, can decrease the amount of toxic fats in the liver.

“People have to realize that elafibranor activates PPAR alpha, as well as PPAR delta. It hits on both of those targets. Seladelpar works only on PPAR delta,” explained Hum.

“There is no reason why people should be making this crossover from the seladelpar data to the elafibranor data because at the end of the day, elafibranor has histology data and that’s going to trump any other endpoint or any other parameters other programs will look at. In our phase IIb [results], we see resolution of NASH, we see decreased cardiovascular risk factors and even after a one-year treatment, no safety or tolerability issues.”

Several competitors are only targeting the tissue scarring or fibrosis seen in the liver in people with this condition, but Hum believes this may be shortsighted. “We have to realize that a drug that works only on fibrosis will not treat the underlying cause of the fibrosis and it will not treat the underlying cause of disease progression. For that, you need a drug that’s able to resolve NASH.”

Instead, he believes a combination approach might be key. Indeed, Genfit is also developing an antifibrosis drug candidate, nitazoxanide, which is currently in phase II trials. If elafibranor and nitazoxanide reach the market, the hope is that the drugs could be used in combination depending on individual patient requirements.

Hum believes that while the NASH field has taken time to develop, it is now poised to take off.

“I think the whole field has been waiting around and looking at the pioneers in this space… looking to see how those programs move forward before they jump on the bandwagon. This is how we got from having only three programs in NASH to now over 50 clinical-stage programs,” he explained.

“Key pieces of the puzzle came together in the whole field. One is a better understanding of the natural history of the disease… Another important piece of the puzzle was the regulatory landscape has cleared up somewhat. Now, the FDA has published draft guidelines on the endpoints which they would be accepting for drug registration, but that draft guideline was only published in December 2018.”

It has been a long time coming, but investors, patients and many others in biotech await the results of Genfit’s phase III trial with keen interest. It remains to be seen whether they will triumphantly bring the first NASH drug to market in 2020, or if they will fall victim to the curse that seems to be impacting other companies in this space.

Images via E. Resko and Shutterstock