Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Using the gene editing tool CRISPR-Cas9, researchers in Lausanne have uncovered antimicrobial molecules in the fruit fly that can selectively kill certain bacteria. This could lead to new therapeutics combatting antimicrobial resistance, and even preventing infections before they start.

The research shows the antimicrobial molecules, or peptides, have the potential to treat infections of pathogens such as gram-negative bacteria, some of the hardest bacteria to treat. The peptides could also provide the basis for a viable alternative treatment for drug-resistant superbugs, such as strains of Providencia rettgeri, which can cause urinary tract infections and travelers’ diarrhea.

Innate immunity is the first line of defense that the body has against invaders, before the more targeted weapons, such as T cells and B cells, pitch in. One key part of this first defense is antimicrobial peptides, which attack pathogens and can prevent them from gaining a foothold.

“By understanding antimicrobial peptide modes of action, we can better understand not only how to treat infections, but even better: how to prevent them in the first place,” Mark Hanson, who led the study at the Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, told me.

In spite of this potential to prevent infection, not much is known how about these peptides work in whole organisms, with the bulk of research carried out on cells in Petri dishes.

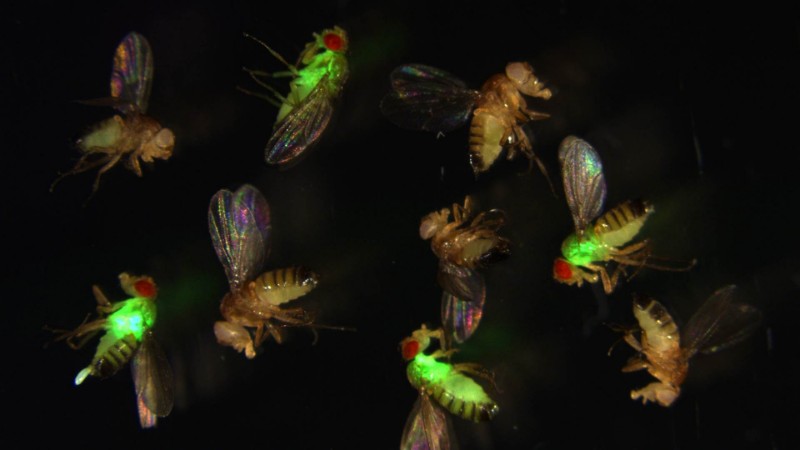

To unpick how antimicrobial peptides work in living animals, the researchers used the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, which is a common model organism for human health. In this fly model, the research group deleted the genes for up to 14 antimicrobial peptides using CRISPR-Cas9. The researchers then tested the fly’s immune defenses against certain species of pathogens.

In the study, published in eLife, the researchers found that the fly’s antimicrobial peptides mainly target gram-negative bacteria and that some were unexpectedly specific for particular pathogens, such as P. rettgeri. This specific action of the antimicrobials in the living model flies in the face of previous lab-based research that suggested these molecules work together and weren’t specific for any particular pathogen.

The research group speculated that the innate immune system throws every single antimicrobial peptide it can at invaders, hoping to land a ‘silver bullet’ that can dispatch the invading species.

The scientists have no immediate plans for commercializing this research, but are open to the therapeutic potential of antimicrobial peptides in face of the looming crisis of multi-drug resistant superbugs, many of which are gram-negative bacteria.

There is already interest in using antimicrobial peptides from insects in biotech for this very purpose. Scientists in Zürich are studying the potential therapeutic benefits of an antimicrobial peptide in another insect, the spined soldier bug Podisus maculiventris.

Images from Shutterstock and Mark Austin Hanson, EPFL