Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Antivenoms could one day be made in the lab instead of in animals. Researchers from the Technical University of Denmark have neutralized black mamba venom in mice with lab-grown human antibodies for the first time.

Snakebite is a serious problem, causing the deaths of around 100,000 people every year, and about three times that number suffer permanent disabilities. Developing countries are more affected by this problem than developed countries.

Getting the right antivenom for each snake venom is fraught with difficulties. “Current antivenoms, which are the only existing treatment, are scarce and expensive,” Andreas Laustsen, the self-branded ‘Snakebite Jesus’ from the Technical University of Denmark and lead author on the study, told me. “This has the result that the majority of snakebite victims in many tropical regions of the world are left untreated.”

Conventional antivenoms are produced by injecting mammals, such as horses, with a small dose of the venom, and then collecting their antibodies against the venom. The drawback of this is that the antibodies vary in effectiveness and patients can have adverse reactions due to the animal origin of the treatment. There is thus a clear need for safer antivenoms.

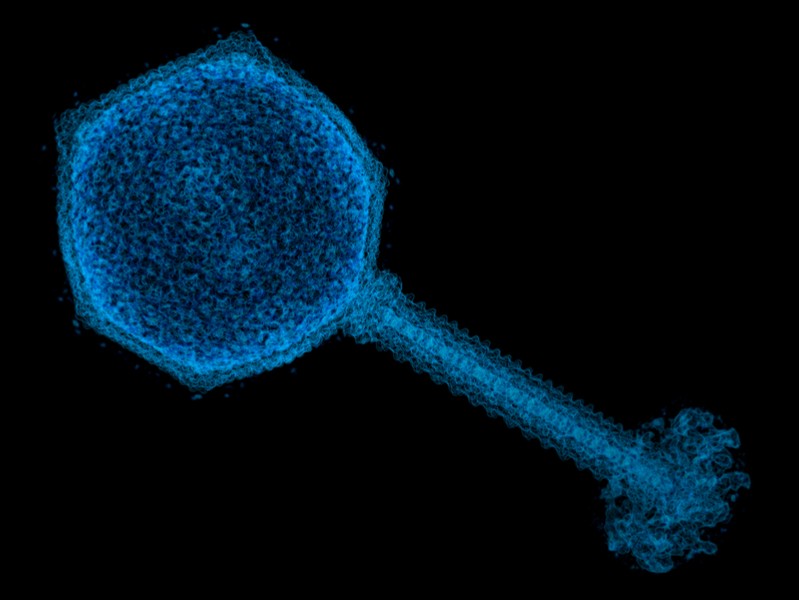

The research group generated new lab-grown human-derived antivenom against the venom of the black mamba, a snake species that produces dangerous neurotoxins. To do this, they grew human antibodies on the surface of viruses that infect bacteria, called bacteriophages. They then used black mamba toxins to ‘fish’ for the best binding antibodies in the sea of bacteriophages.

Once they had the best antibody for the black mamba toxins, Lausten explained, the team could extract its genetic blueprints and produce more of it, before testing it in whole animals.

In a recent study in collaboration with British company Iontas and the Instituto Clodomiro Picado in Costa Rica, the researchers used these lab-grown human antibodies in mice after giving them black mamba venom. The treatment improved their survival to up to 100% whereas untreated mice died.

Although still far from the clinic at present, these lab-grown antibodies could be a safer source of antivenoms than current treatments, as Lausten enthused: “It’s a new approach for developing a fundamentally new type of antivenoms against snakebite.”

Lausten is the co-founder of a biotech called VenomAb that is developing methods of manufacturing antivenom antibodies.

Notably, too, the inventor of the technique that the researchers used to fish out antivenom antibodies, phage display, was the joint winner of the Nobel Prize this week.

Images from Shutterstock

Are you interested in antibody therapy R&D?