Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Genetically modified insects are released to control the spread of diseases and crop pests, but the logistics may not be so simple: these little creatures could jam global food exports, particularly to more GM-averse Europe.

What happens when genetically engineered insects develop on vegetable farms? Two researchers, from the Max Planck Institue for Evolutionary Biology in Germany and the University of Saskatchewan in Canada, say import bans, trade disruption and consumer distrust are likely. Their study was published in the journal Sustainability.

Genetic modification of insects is used to create a self-limiting population. It’s a technological successor to the Sterile Insect Technique, in use for over 50 years, in which males are sterilized by radiation. However, radiation can affect many different genes and the ability of the insects to mate. Oxitec, a spin-out of the University of Oxford, has a more precise solution in mind: a single genetic modification that only affects the viability of the offspring.

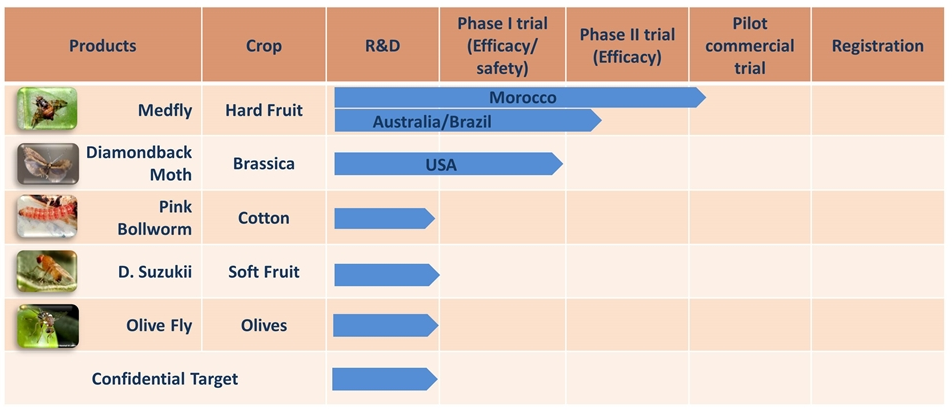

The company has already carried significant field trials, related to infectious disease control, in Brazil and the United States, with the FDA finding no evidence of negative impact. While there was some degree of public backlash to the release of GM insects, it didn’t nearly reach the same level as the debate surrounding crop modification.

However, Oxitec is also developing products for pest control in agriculture. In 2005, there was a small field trial that involved the release of an engineered diamondback moth, a common pest, on 40,500 square meters of cabbage and broccoli fields in a remote location of the New York state. For the researchers, this first trial on GM insects in agriculture exemplifies some of the challenges this approach may pose. Insects will fly from farm to farm and there has been little discussion regarding how to prevent contamination in the fields of farmers who don’t want a GMO solution. Currently, local farmers aren’t required to be informed of mass releases.

A particularly vulnerable group are organic farmers, which depend heavily on reputation. As of now, international “100% organic labels” do not take nearby field trials into consideration, but that may change if this becomes perceived by consumers as GMO contamination. On a wider scale, GM insect contamination could step on legal toes. In the European Union, where the approval of GMOs lags behind the US or Asian countries, the presence of these insects would go against regulations. Digging into previous legal cases, the researchers say that import bans are a possibility.

While there’s a scientific consensus that GMOs are safe and Oxitec’s technique is showing a lot of potential as a solution to the spread of infectious disease, “releasing flying genetically modified insects without considering the likely impact on sensitive groups of farmers is unwise and unnecessary,” says one of the authors, especially if the technology is to not fall in the same swamp of controversy as GM crops.

Images from Intrexon