Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Scouring the natural world can be an effective way of finding design inspiration for new scientific innovation. Several biotech companies are using biomimicry to develop weird and wonderful bio-inspired products.

If you’re looking to design a new tool to overcome a scientific challenge, chances are that evolution has beaten you to it. It’s not exactly a fair competition — nature has been conducting research and development for billions of years longer than humanity.

It is no surprise then that scientists and engineers across all disciplines are increasingly turning to biomimicry — looking to the natural world for inspiration — to create everything from wind turbine blades that mirror the aerodynamic efficiency of whale fins, to super-fast trains with noses based on the streamlined shape of the kingfisher’s beak, or self-healing cement tiles that use the ability of bacteria to produce limestone to repair any cracks.

We’re seeing an increasing number of ideas and products that have their roots in biomimicry. After all, why attempt to create something from scratch when you can just raid nature’s toolbox?

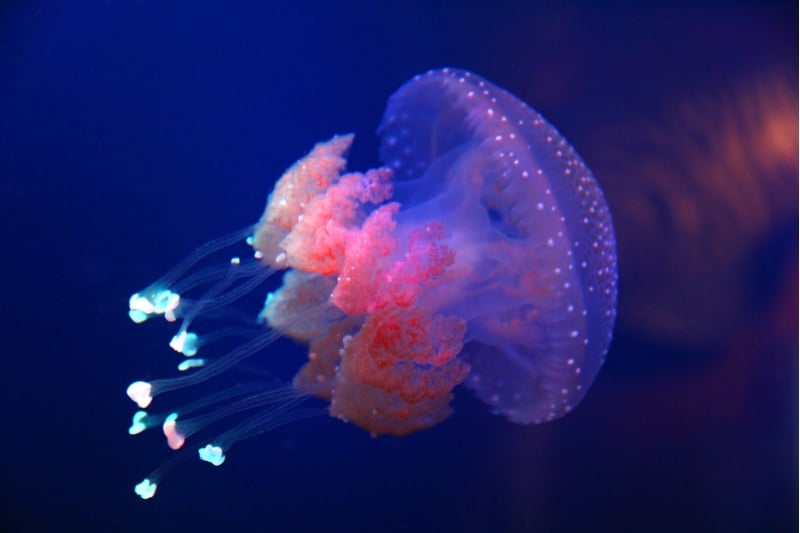

Jellyfish collagen

Jellagen, a Welsh marine biotechnology company, has its eyes on the unassuming jellyfish as a source of a potential revolutionary biomaterial: next-generation collagen.

The idea first came to Jellagen co-founder Andrew Mearns Spragg in his youth, after encountering huge blooms of jellyfish while surfing off the east coast of Scotland. Human activity has caused jellyfish populations to explode, and while most saw this as a nuisance, Mearns Spragg saw it as a valuable resource for the future.

Collagen is the most abundant protein in mammals and is a key component of almost all types of tissue. Meaning that it has a variety of uses in the medical, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries, which currently source their collagen from mammals — mainly cows, pigs, and sheep. However, there are a variety of concerns around mammalian collagen, such as the potential for disease transmission, which has led to the need for a safer collagen source.

Enter jellyfish.

“Jellyfish collagen is an evolutionary ancient chemical template and is where all collagens up the tree of life have been derived. Jellyfish collagen is the root of all collagens, compatible with a broad range of cell types,” Mearns Spragg said.

Not only is jellyfish-derived collagen safer and disease-free, but it also has a low propensity to elicit an immune response from the immune system. This makes it an ideal alternative to mammal collagen.

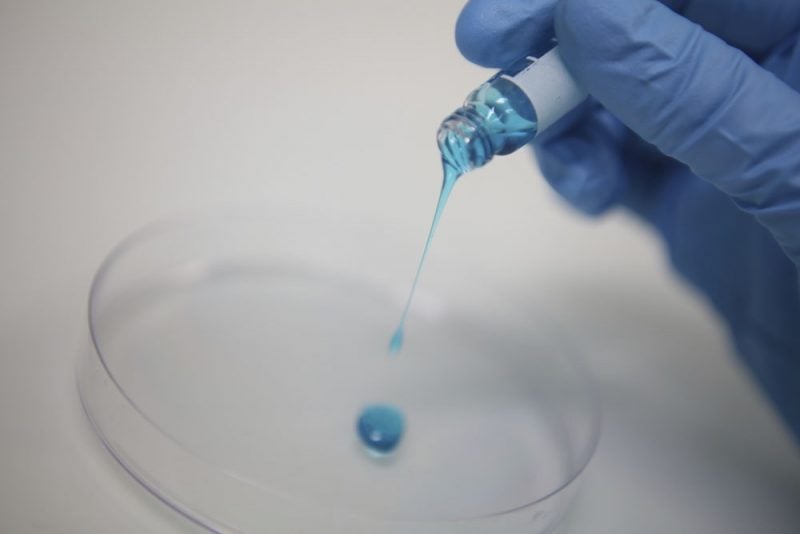

In early 2021, Jellagen launched a collagen material used to culture cells for research purposes. The company is also working on different uses of its collagen in therapeutic applications as well as medical devices, including for wound repair, regenerative medicine, and tissue engineering. It’s a powerful example of how biomimicry allows us to find solutions in nature, even in the unlikeliest of places.

Wooden bones

GreenBone is an Italian startup with a mission to develop an innovative bone graft scaffold for patients with bone defects. These patients, whose defects may be due to trauma, infection, cancer, or simply an unhealed fracture, face very few options if the damage spans more than a few centimeters. To tackle this, GreenBone looked to nature and identified rattan — a plant similar to bamboo — as an ideal starting material for a scaffold to allow bone regeneration.

“A nature-inspired project to find new biocompatible materials able to sustain tissue regeneration in orthopedics prompted a screen for plants that have a similar internal structure to bone,” explained Lorenzo Pradella, GreenBone’s co-founder and CEO.

“The researchers identified rattan as the best candidate, as it has a comparable load-bearing capacity and an internal 3D architecture that incorporates xylem-transporting channels, which mimic the way blood vessels run through bone.”

The rattan wood is shaped according to the dimensions of the bone defect. It then enters a chemical process that preserves its structure and shape but removes any biological components of the wood. The end result is a white calcium phosphate scaffold with an internal porous architecture that mimics the structure of bone. Once the material is inserted into the defect site, the patient’s bone cells are able to move into the scaffold and eventually form new bone tissue.

Pradella is confident that the company’s biomimicry approach will be a game-changer for sufferers of bone defects. “GreenBone is expected to enable patients a faster return to normal life with their own bone completely regenerated. This will provide a tremendous improvement in patient quality of life reducing and, at the same time, health and social costs.”

Designing such a scaffold from scratch would have been a tall order. “Looking into nature to find inspiration for such innovative bone substitute gave the opportunity to use ‘existing in nature’ bone-like architecture.”

Worm glue

Paris-based Tissium (formerly Gecko Biomedical) is the developer of a sealant used for vascular surgery that is based on the glue-like secretions of the Californian sandcastle worm.

Sealing internal wounds is notoriously tricky. Conventional surgical glues often have trouble staying in place due to the constant motion of the body. They can also react with the surrounding moisture, rendering them less effective.

Tissium’s sealant, by contrast, is designed to be viscous and hydrophobic, meaning that it has much less difficulty staying in place and isn’t disturbed or washed away by moisture. Once it is applied over the wound, the surgeon shines a UV light onto the glue which causes it to solidify in mere seconds.

“The problem we were trying to solve was the design of an adhesive strong enough to withstand blood and constant movement, with a minimally invasive application procedure,” CEO Christophe Bancel explained.

This sealant glue was inspired by the Californian sandcastle worm. This marine worm is famous for its ability to secrete an adhesive that it uses to glue particles of sand together, allowing it to build protective tubes. This adhesive secretion has been perfected through millions of years of evolution to set quickly and also to work in wet environments without difficulty – an ideal design to copy for a surgical glue.

A clinical trial of 22 patients receiving a carotid endarterectomy (a procedure to remove plaque in the carotid artery to reduce the risk of stroke) demonstrated that the use of the sealant resulted in immediate sealing of the incision in 84% of patients.

The company is developing several other applications for this technology, including nerve reconstruction and hernia repair. “[Our sealant] is the first of its kind in the bio-inspired category, and it’s just the first step in the process of establishing the company as an innovator in support of better healing.”

——–

Evolution has scattered time-tested designs across the biosphere. From jellyfish blooms to tropical rattan plants, to marine worms, inspiration can be found almost everywhere. When it comes to biomimicry, we’re limited only by our curiosity about the natural world.

Cover image by E. Resko, images via Jellagen, GreenBone, and Gecko Biomedical. This article was published in September 2018 and has since been updated to reflect recent developments.

Partnering 2030: FME Industries Report