London’s Science Gallery has gathered scientists and artists to create an exhibition that lets visitors peek at a not-so-distant future where custom implants and organ regeneration become the norm.

The field of regenerative medicine has taken huge strides forward in recent years. Today, there’s talk of stem cells, smart implants, and 3D-printed organs all over the media. But for those outside the field it is difficult to know what is fact, what is fiction, and what the consequences of these technologies will be in society and in our daily lives.

The exhibition Spare Parts, open in London until May 12, invited scientists and artists to work together and challenge the assumptions of visitors, letting them peak at the reality of the future of medicine and reflect on the implications.

“Both scientists and artists depend on observations,” says Lucy Di Silvio, Professor at King’s College London and one of the scientists behind the exhibition. “We scientists embody the rational and analytical, while artists are more expressive and empathic. The combination works very well; working with artists has allowed me to engage with the public in communicating an otherwise difficult topic.”

Crafting the body

Di Silvio’s research focuses on recreating replacements for damaged or diseased tissues. She investigates how different materials can influence cells to behave differently with the goal of making cells form tissues.

She was surprised when Amy Congdon, a textile designer at Central Saint Martins, showed interest in her work. “To be honest, when she first called I told her she had the wrong department,” Di Silvio told me. But when they met, they spent hours talking about the many things their work has in common.

“Amy talked about how she created her textiles to achieve different textures, open and closed weave, embroidery, orderly and non-orderly patterns, embellishing with beads and stones…” said Di Silvio. “It was very similar to creating tissue substitutes, where we need to consider the tissue, its properties, its hierarchical structure, and the ability of the cells to attach, migrate and grow across the different materials.”

They decided to work together to explore the intersection of their areas of expertise. Amy selected a range of materials including silk, cotton, starch and horsehair, and created embroidered surfaces. Di Silvio tested how human cells grew on them. “Essentially, we demonstrated that a tailored textile can control the level of cell attachment and alignment required for tissue repair,” she said.

Their exhibit ‘Crafting the body’ presents samples and videos of their work in the form of a fictional atelier in a future where people can be implanted with couture body parts to replace damaged tissues with a living ornament.

The self-donor workshop

While we all love to imagine what the future will be like, Slovenian artist Tina Gorjanc realized that her own perception of emerging bioengineering technologies was heavily influenced by the hype behind them. “The advertisement of such research sometimes over promises and underestimates the timeframe of their implementation into everyday medical procedures,” she told me.

Her exhibit, ‘The self-donor workshop’, aims to give a more realistic view of what current research in regenerative medicine will let us do in the short term future. “While customized human organs are still far from being a reality, it may soon be possible to engineer organoids that would improve certain bodily functions,” said Gorjanc.

The exhibit highlights the work of researchers that advocate for creating biological structures that have the same function as a human organ without necessarily looking the same. Gorjanc creates the scenario of a bioengineering boutique where a person’s cells are grown into simplified versions of an organ that act as ‘add-ons’ to improve the performance of their organs. “The proposed ‘mini organs’ might have a better shot at improving the patients’ quality of life,” she explained.

The visitor is presented with a model of the human torso, like the ones often used in schools to teach anatomy, from where the organs can be taken out and inspected. In a nearby table there’s a series of bags of biological matter labeled with fictional brand names — which intends to reflect on the way these technologies have led us to see our own cells and bodies as products. Gorjanc also exposes how medical research is often standardized to a one-size-fits-all solution while each human body is “a totally diverse and individual entity.”

Big heart data

A wall covered with 3D-printed replicas of real human hearts highlights how different from each other they can be. The exhibit, ‘Big heart data’, draws inspiration from the research of Pablo Lamata, a lecturer at King’s College London.

“The message is that the shape of the heart is also a signature of the lifestyle choices you take, and of the disease process that the cardiologist is following,” Lamata told me. His research team studies how lifestyle and disease affect the heart shape, and, in turn, how that can guide better treatment decisions in people with heart conditions such as heart failure or aortic valve stenosis.

Lamata worked with French designer and artist Salomé Bazin to show how precision medicine looks at the variability between individuals to tailor treatments to each patient. In recent years, this approach has gained traction in the treatment of cancer, and it is extending to many other areas of health.

“We illustrate how we are capturing the anatomical variability as the first step towards the vision of an ‘in-silico cardiology’, where computer models analyze data and make predictions about different therapy options with unprecedented power,” said Lamata.

Working with Bazin has been an opportunity for Lamata to approach his work in a different way than usual. “She definitely pushed me to think out of my ‘scientific box,’” he said, adding that such a refreshing artistic project had created an unexpected amount of motivation within the research team.

Microbiome rebirth incubator

The human microbiome — all the microorganisms that live in and on our bodies — is gaining recognition as one more of our body’s organs given all the roles it plays in regulating our health. Scientists believe that our microbiome is established at birth, when the vaginal microbiome is transferred to the baby. However, that doesn’t happen during a C-section — something that art historian Marianne Cloutier has gone through herself.

“When a mother knows in advance that she will have a planned C-section, it is possible to practice vaginal seeding as a way to partially restore the microbiome of babies,” she told me. “To do so, a sterile cloth is to be placed in the mother’s vagina prior to birth, and then the baby’s mouth, face and body are wiped with the mother’s microbiome.”

Cloutier teamed up with Canadian artist and scientist François-Joseph Lapointe (he has a PhD in evolutionary biology and another in dance and performance), to create an exhibit that reflects on this experience.

“The fact that 50% of the cells in our body are not human cells challenges the concept of self,” Lapointe told me. “How is the bacterial identity of the mother transmitted to her newborn at birth?”

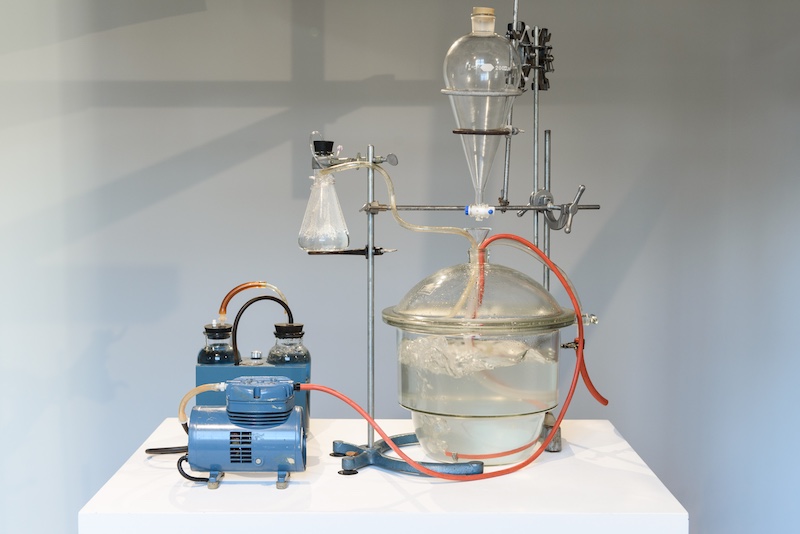

The artwork consists of a glass ‘incubator’ containing physiological serum that plays the role of amniotic fluid. Through series of flasks and tubing, the liquid was seeded with vaginal bacteria and breast milk — another way mothers pass down bacteria to their children. “The probiotic cocktail contained in the incubator may then be used to seed babies born by C-section with the mother’s microbiome,” said Cloutier.

Lapointe pointed out that the jury is still out about the long-term effects of vaginal seeding. “Although we are not promoting, nor preventing this approach, our work raises important questions,” he said. “It is already known that babies born by C-section are more likely to become obese and develop autoimmune diseases and allergies. Some researchers are already testing probiotic pills for babies, and recent studies have shown that the microbiome of breast milk is different from that of expressed milk.”

Knowledge is power

The many fascinating exhibits featured in ‘Spare Parts’ take topics and issues that are very current and make them accessible to every visitor. There are many discussions in the scientific community about what the future should look like in fields as current as regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, precision medicine and the human microbiome. Often the public is left out of this discussion, even if they will be directly affected by these technologies.

Bringing artists and scientists together proves a great way of engaging with the public and starting a discussion where they can actually participate.

“An unexpected realization was evidencing the importance and power that we as members of the general public actually hold when it comes to promoting and funding future research,” said Gorjanc. She believes exhibitions that expose both the possibilities and the problematics of such complex research can help visitors take informed decisions and transform into “actors of change.”

Images courtesy of Science Gallery London