Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Scientists are uncovering many ways that the microorganisms that share our body can influence our health. It appears as though the human microbiome could be the key to treating all sorts of diseases, but how can we make these tiny creatures collaborate with us? Let’s do a gut check.

We’ve all been told that our DNA is what makes us what we are. What many don’t realize is that that DNA does not come exclusively from our own human cells. It also comes from the millions of microbes that live on our skin, inside our gut, and pretty much everywhere in the human body. Their genes outnumber ours by 150 times.

Some scientists refer to them as our ‘second genome,’ and some even consider them one more of our organs. The term microbiome was coined by Nobel Laureate Joshua Lederberg. He described it as “the ecological community of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic microorganisms that literally share our body space and have been all but ignored as determinants of health and disease.”

In the last decade, though scientists are becoming aware of the potential of the human microbiome. “It has become evident through research that the microbiota that humans carry have a significant impact on human health,” Lee Jones, founder and CEO of Rebiotix, told me. Her company, recently acquired by the Swedish Ferring Pharmaceuticals, is one of many that seek to exploit our tiny life partners to treat disease.

The potential seems unlimited. The human microbiome has been linked to all sorts of conditions, ranging from inflammatory bowel disease to diabetes, multiple sclerosis, autism, cancer, and AIDS. This has created an explosion in microbiome research. “The technologies that allow us to analyze this impact have improved at an exponential rate, making discovery much easier than even five years ago,” said Jones.

However, understanding the complexity of the microbiome is still a big challenge. Its composition is unique to each person and changes through life as does our environment. The human microbiota can be affected from all sorts of factors, ranging from diet — for example, vegans and vegetarians have a distinct gut microbiome — to exercise habits, age, location, and many more we might still not know of.

The microbiome is also different in each part of the body. In particular, the gut microbiome is the one that is being researched the most, hoping to unravel the huge potential hiding behind the complex interactions between microbes and with their host.

Where will the microbiome have the most impact?

In 2018 alone, over 2,400 clinical trials were testing therapies based on microbiome science. That number is growing quickly, as in comparison there were just 1,600 the previous year, according to a report by Seventure Partners, a French VC investor with a fund dedicated to companies in the microbiome space as well as nutrition, digital health, and food technology.

As microbiome research has grown, more and more health conditions have been linked to having an unbalanced microbial composition — something known as dysbiosis.

“It all started with the gastrointestinal indications, and the metabolic indications,” Isabelle de Cremoux, CEO of Seventure, told me. “Then we saw innovations applied to the field of autoimmune and immune diseases. Then skincare popped up and more recently the gut-brain axis and oncology are gaining momentum.”

Although the microbiome can be disruptive in all these fields, de Cremoux believes that, from a market perspective, oncology has the biggest potential.

It is known that some microorganisms render cancer drugs ineffective, whereas others are actually necessary to make these drugs work. Meaning that having the right microbiome might massively affect the chances of a person surviving cancer.

“The gut microbiome has emerged as an important target in cancer therapy to repair the microbiome following harsh chemotherapy and antibiotic treatment regimens to improve patient survival. We see also more and more correlation between the microbiome and immunotherapy’s efficacy and most recently in cellular therapies,” said Hervé Affagard, CEO of MaaT Pharma. This Paris-based company aims to improve the chances of patients with leukemia by restoring a healthy microbiome after being disrupted by chemo and antibiotics.

How do we target the microbiome?

Some of the first attempts at treating the microbiome can be traced back to China thousands of years ago, when doctors treated diarrhea with so-called yellow soup — basically dried stool from a healthy person. Today, the practice is known as fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) and is delivered in the more pleasant form of frozen capsules. MaaT Pharma has tested this technique to help patients recover from leukemia, while Rebiotix is using it to fight C. difficile infections and ulcerative colitis.

Others focus on identifying a specific bacterial strain, or group of strains, that is delivered alive to the patient’s gut. In the UK, a young company called Microbiotica fights Clostridium difficile infections, as well as IBD and cancer, by transferring non-pathogenic strains of C. difficile to the patient. The firm has set out to rival the likes of US-based Seres Therapeutics and Vedanta, which is partnered with Janssen to treat IBD through the microbiome.

Some are skeptical of the potential of consuming live bacteria, arguing that they would have to compete with those that have been living there for years, therefore flushing out rapidly and failing to actually impact our health. “If you look back to over 50 years of clinical research on probiotics, there is no demonstration of clinical efficacy of live bacteria,” Pierre Belichard, CEO of Enterome, told me bluntly.

Based in Paris, Enterome develops drugs that specifically target the bacteria that cause disease while leaving the rest of the gut microbiome intact. The company’s most advanced program is being tested in Crohn’s disease, while other programs look at ulcerative colitis, IBD and cancer. Other companies following a similar approach are Second Genome and C3J Therapeutics in the US and Infant Bacterial Therapeutics in Sweden.

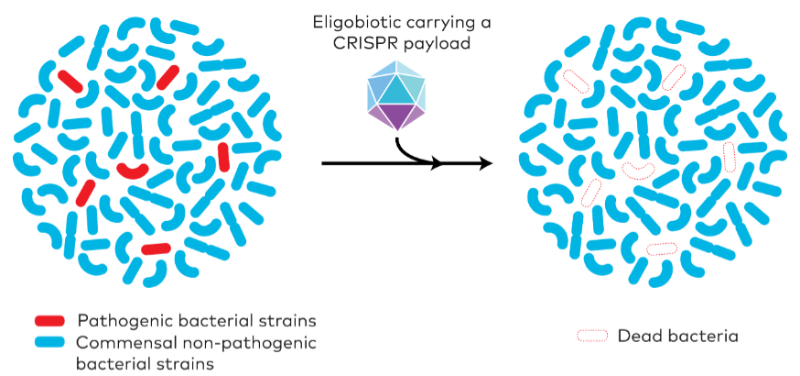

Another way to target the microbiome makes use of viruses called bacteriophages that have evolved over millions of years to only infect and kill very specific strains of bacteria. This approach is used by EpiBiome in the US and BiomX in Israel, but the French startup Eligo Bioscience takes this concept a step further. The company uses the viruses to deliver the gene editing tool CRISPR/Cas9 into the bacteria. Once inside, CRISPR kills the bacteria by cutting their DNA, but only when a specific DNA sequence is present in the microorganism. Thus, even within the same bacterial strain, only those that carry a gene that causes disease are eliminated.

In Denmark, the company SNIPR Biome also uses CRISPR gene editing to selectively kill problematic bacteria without damaging the rest of the microbiome.

Finally, certain companies engineer bacteria to become drug factories directly within the human gut. Among them are Blue Turtle Bio and Synlogic in the US, and Anaero Pharma in Japan.

Given the complexity of the microbiome, having such a wide range of approaches to treat it can be an advantage. “For some diseases certain modalities are better,” said de Cremoux. “For example, fecal microbiota transplantation is a very low hanging fruit for many diseases linked to cancer. Live bacteria are well-suited for food allergies and certain immune and chronic diseases.”

Fighting the challenges

“Knowing the link between gut dysbiosis and metabolic diseases, the potential is huge, of course. But it needs much more science, and new science based on new methods, to completely tap this potential,” said Murielle Cazaubiel, CMO from Valbiotis. One of the drugs in the pipeline of this French company targets gut dysbiosis induced by a high-fat diet in order to prevent obesity.

One of the biggest challenges in microbiome research is determining whether a change in the microbiota is actually responsible for a specific condition, or if it is just a ‘side effect.’ The complexity of the microbiome, and the fact that each person has a distinct one, makes it extremely difficult to determine cause-effect relationships.

“At this time, it is not clear if the changes observed in the microbiome in patients with different diseases are the cause of the disease or the result of the disease process. This makes it challenging to know how to approach product development,” said Jones.

Another challenge has been translating lab results to clinical trials. As de Cremoux pointed out, improving animal models will be an important step for the field.

“A challenge in the near term, as the field matures into later stages of clinical development, can be navigating the regulatory processes related to different microbiome-based products,” added Affagard. His company, MaaT Pharma, is part of a group pushing to reform European regulations to make the approval of microbiome therapies easier to navigate.

What’s on the horizon for microbiome research?

As researchers work to unveil the multiple links between the microbiome and human health, we are getting close to seeing the first microbiome therapies in the market. Rebiotix is developing a therapy for C. difficile infections that, according to Jones, “has the potential to be the first human microbiome product approved anywhere in the world.”

De Cremoux believes that 2019 will be an inflection point for microbiome research. She expects data from phase II and III clinical trials that will finally yield results showing whether microbiome treatments do work in humans.

Financially, the field is also rapidly growing. In the last few years, many big names in the pharma industry, such as Merck, Takeda, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb have signed generous partnerships with microbiome companies. Even Microsoft has decided to enter the field. Lonza, a pharma supplier, has seen the opportunity and launched the first company to offer a full supply chain to manufacture live bacterial treatments.

In 2018, we saw the first acquisition of a microbiome company, Rebiotix. In 2019, de Cremoux expects to see these companies entering the public market, and potentially some new acquisitions. This should also encourage private investors to venture in the field.

“Advances in machine learning algorithms that can be applied to the large data sets… will make it possible to effectively find correlations in the complex interactive network between the host and their microbiome,” said Affagard.

With new advances in machine learning and diagnostic techniques, microbiome research will keep growing and becoming more precise. “The exploration of the microbiota paves the way to a brand new personalized medicine. This could allow us to offer the most adapted option to each condition,” said Cazaubiel.

As with any other field in its early stages, there will certainly be many ups and downs in microbiome research. As researchers work out the limitations, it seems clear that the microbiome will definitely bring very exciting solutions to many medical challenges.

“We are excited to learn more about the influence the microbiome has over our daily lives, and how the microbiome can be augmented or changed to potentially improve health. We look forward to finding the link between the microbiome and extremely complicated indications, such as obesity, cancer, diabetes and infertility,” said Jones. “The potential is only limited by the imagination of industry and medicine.”

This article was originally published on January 2018, and has since been updated with new quotes and up to date figures. Images via Shutterstock.