Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Many biotech companies deploy strong chemicals to clean and disinfect their equipment. However, if handled in the wrong way, this can lead to dangerous problems such as antibiotic resistance. As the EU prepares to release new guidelines on good manufacturing practices, it’s time to revise how cleaning is approached in the industry.

To effectively control contamination and ensure sterile work processes, the biotech industry is increasingly turning to harsh disinfectants. This trend roots in the common belief that aggressive disinfectants are the most efficient remedy, explained Angelika Hassler, quality manager at comprei, an Austrian company with over 20 years of experience in cleanroom maintenance.

According to Hassler, this conception does not hold. “If the right strategy is in place and executed with proper materials by well-trained employees, it is not necessary to use aggressive agents.”

While aggressive cleansers and disinfectants do not necessarily give a better result than mild products, they can entail several adverse effects. For example, chlorine-based agents are not only aggressive against germs, but also towards work surfaces, which can wear down scientific equipment. Additionally, they can cause respiratory or vision problems in cases of prolonged exposure. Adverse health effects have been reported for other commonly employed biocides too, such as triclosan.

Aggressive strategies increase antibiotic resistance

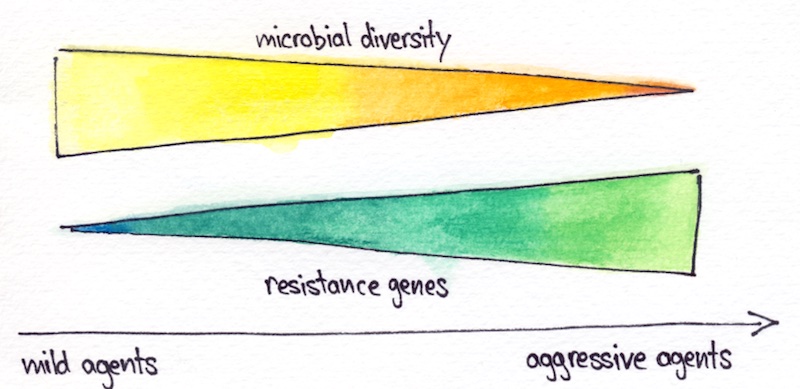

According to a report in Nature Communications last year, more stringent cleaning practices correlate with the emergence of microbes that are resistant to antibiotics. This could make containment of the microbes more difficult and potentially result in economic losses. The switch to a milder cleaning and disinfection routine can, thus, help control biological contamination more effectively in the long run.

The researchers found that antibiotic resistance was more common in intensive care units and industrial cleanrooms — two highly controlled sites — than in uncontrolled environments, like public buildings and private homes. Still, according to Alexander Mahnert, researcher at the Graz University of Technology and one of the authors of the study, the situation is not as critical in cleanrooms as it is in intensive care units.

It is yet unclear how exactly aggressive cleaning and disinfection leads to the enrichment of antibiotic resistance. Or which specific antimicrobials are responsible. Recent studies have pointed towards benzalkonium chloride and triclosan. For example, benzalkonium chloride can cause bacteria to spread genes against biocide and antibiotic compounds. Triclosan, on the other hand, can stimulate certain bacteria to take up DNA from the environment, which can include antibiotic resistance genes.

Mahnert emphasized that cleaning agents are not all alike. “A cleaning agent does not necessarily promote resistance and it is important to discriminate between antimicrobial and normal cleaning agents.” Soap, bleach, and alcohol-based detergents affect the external barrier of bacteria. While they may enrich the amount of Gram-positive bacteria, which have a stronger external barrier, these cleaning agents are less likely to cause and spread resistance.

It is noteworthy that the presence of an antibiotic resistance gene is not necessarily a health risk. “Not all resistances are bad,” stated Mahnert. Antibiotic resistance has existed for millions of years, and a great diversity of resistance genes evolved before humans started using antibiotics. Not all these natural resistance genes present a threat to human health.

“If there is a resistance gene in bacteria that are not able to colonize the human body, it is a completely different risk than if the same gene is in bacteria that are capable of colonizing humans,” said Célia Manaia, a microbiologist at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa in Lisbon.

In addition, for antibiotic resistance to pose a risk there needs to be sufficient amounts of the bacteria that carry it. “The pressure of extensive disinfection and really aggressive cleaning seems to increase antibiotic resistance or enrich for a certain set of very hardy organisms. But at the same time, the overall [indoor microbial] biomass is very low, so that the potential for an encounter may also be low,” said Erica Hartmann, Assistant Professor at Northwestern University.

The new EU guidelines on cleaning and disinfection

Since 1971, Annex 1 of the EU good manufacturing practice (GMP) guidelines has set principles to ensure that sterile medicinal products enter the market. After occasional updates and amendments, the annex is currently undergoing a complete revision and could come into force within several months.

The current draft of the new guidelines, which is now in a consultation period, is introducing changes to the directives on cleaning and disinfection of sterile zones. One of the key changes is that cleaning before and after disinfection is going to become a prerequisite.

To effectively inactivate microorganisms, the disinfectant has to reach and get in contact with the microbial cells. The inactivated microbes, however, can still remain and spread to other areas where they serve as a breeding ground for new microbial generations, said Hassler. Wiping off the dead microbial biomass before and after disinfection, a three-step process that will be required by the new guidelines, averts this problem.

“Generally, it represents a problem that is often underestimated. The stricter guidelines, therefore, rule out a certain basic risk,” said Hassler.

Cleaning after disinfection is also necessary to remove disinfectant residues. Because if the disinfectant is not cleansed away, small amounts that are not lethal to microorganisms can remain, allowing them to develop tolerance or resistance to the product.

“Where you have the chemical at sublethal concentrations is where I think the concern for enriching antibiotic resistance takes place,” said Hartmann.

The new draft further lays out the turnover of disinfectants, establishing that at least two disinfectants should routinely be in use. “It is a good practice that should be developed to combine different disinfection processes, as they are not always equally efficient,” said Manaia.

Disinfectants possess different modes of action and each mode targets a certain range of microorganisms, she explained. Rotating between disinfectants thwarts the enrichment of certain microbes over others, bolstering long-term containment.

The draft also indicates that “disinfection should include the periodic use of a sporicidal agent” but it does not include further details on the kind of agents to be used. Microbiologists advocate for mild cleansers and disinfectants, which are not necessarily less effective than their more aggressive alternatives. Whether harsh or mild agents, to work effectively it is essential to use them correctly.

Human behavior is a big risk factor

While the new requisites on cleaning and disinfection will rule out basic risks, humans themselves remain an important risk factor. Humans spread 10 million biological particles per hour. The presence of many sick people, as is the case in a hospital, leaves a different trace of microorganisms behind than the generally healthy employees in a biotech company.

Manaia sees the presence of unwanted bacteria in the cleanroom as a consequence of insufficient quality control rather than cleaning practices. These microbes can adapt to the conditions of the cleanroom and start proliferating. “This is related to the reduced biodiversity in cleanrooms, which reduces the fight between the organisms.”

Often, the microbes enter the facilities via the personnel. “Human beings are the biggest risk factor in cleanroom areas,” said Hassler. Time and again, she and her colleagues observe that preventive assessments of entry routes of contamination into the cleanroom are not in place.

According to Hassler, awareness on how to preserve cleanliness is often poor, as frequently becomes apparent during practical exercises of her company’s trainings. She emphasizes the importance of training every employee who works inside the cleanroom, be it cleaning staff, production workers, or technicians. “If the background knowledge is missing, even the best hygiene scheme cannot be implemented.”

Soap, the cleanser of choice in non-sterile areas

Common misconceptions about the effectiveness of cleaning agents and the fear of germs has led many people to frequently reach for antimicrobial cleansers. A behavior that was recently showcased as Covid-19 took grip of the world.

“We have traditionally been thinking about ‘scorched-earth cleaning’. We just want to get rid of everything, which is maybe the right choice for cleanrooms but not necessarily the case for basically everything else,” said Hartmann.

Under-cleaning is certainly not beneficial, especially during a pandemic, but nor is over-cleaning. Extensive cleaning and disinfection may do more harm than good as it has the potential to increase the number of resilient microorganisms and decrease microbial diversity.

To maintain offices and other common areas clean, using regular soap will not only suffice, but also bring several benefits. Using stronger agents in offices and other non-sterile sites increases the number of resilient microbes, increasing the risk of staff reintroducing these hardy organisms into sterile zones.

“The less aggressively we try to clean everywhere, the more successfully we will be able to clean in those environments where we really need to,” explained Hartmann. She endorses reserving specific cleaning products for cleanrooms. “These don’t need to be used in offices unless there is some sort of major issue.”

An effective tool to incentivize it outside of the proposed guidelines are taxes, said health economist Laurence Roope. He added that some of these products could even be banned in certain contexts to avoid overuse. “It’s all conditional on the science. Do they bring an extra benefit? What is the damage caused in comparison to regular cleaning agents? At the moment, we don’t have a clear idea of the relative damage caused by different kinds of cleaning products.”

This lack of knowledge is starting to be addressed, according to Hartmann. “We are not quite there yet, but within the next five to ten years we can make some pretty impressive first steps.”

Another advantage of mild cleaning is that it maintains the diversity of the indoor microbiome. Exposure to a diverse array of microorganisms plays an important role in our health. Ideally, that exposure takes place in nature, yet most people spend 90% of their time in buildings, notes Mahnert.

Because of that, microbiologists advocate not only for mild cleaning of offices, but also for establishing a more natural microbial community through plants and frequent ventilation. This microbial diversity then acts as a protective shield to ward off pathogens.

This concept has already given rise to a new class of cleaning agents called probiotic cleaners, which contain live bacteria and fungi. They aim to eradicate pathogenic bacteria while replenishing surfaces with beneficial microbes to form the desired protective shield. Although such products are already commercially available, the technology is in its infancy. Its effectiveness, benefits and risks still need to be assessed.

As the new EU guidelines are enforced, all biotech facilities are going to experience big changes in their maintenance. In cleanrooms, microbial contamination will be controlled through the three-step cleaning-disinfection-cleaning scheme; ideally using mild agents. In all other, non-sterile areas, we may soon not only wipe microbes away but also wipe them on.

Cover illustration by Elena Resko, images drawn by the author