Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

With no drugs that can stop the progression of the disease and hundreds of clinical trials failing, new fields of research bring hope to people with Alzheimer’s.

As the Western population ages, Alzheimer’s disease is becoming one of the biggest diseases of the 21st century. But despite the efforts of science, the FDA and EMA have only approved five drugs for Alzheimer’s so far — none of which can stop the progression of the disease, just manage the symptoms.

This is definitely not for a lack of trying. Over 400 clinical trials were run between 2002 and 2012, but only one drug, memantine, was approved.

The situation has not improved much since then. In the last few years, Merck, Pfizer, J&J, Eli Lilly and Roche have all failed large phase III trials in Alzheimer’s disease.

“It’s the elephant in the room: disease-modifying trials in Alzheimer’s are all failures,” said Niels Prins, Director of the Brain Research Center in Amsterdam, during a panel on neurodegeneration at BIO Europe Spring. “There has been questionable phase II data being transferred too early into phase III.”

One of the most common explanations given to the failures seen in clinical trials has been that it might be already too late to treat patients when they already have advanced symptoms of the disease, and that trials should be run in people with milder, earlier symptoms.

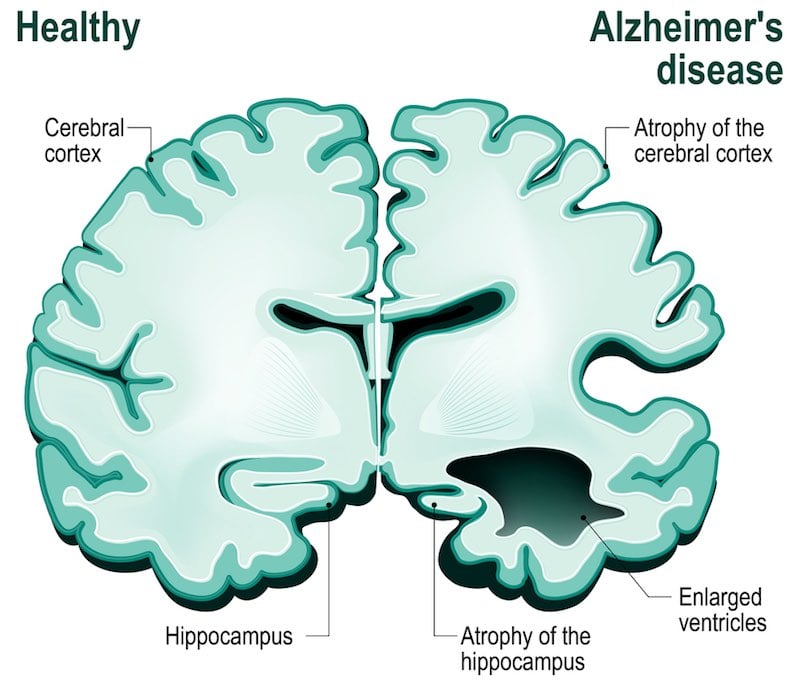

“This last generation of drugs was aimed at clearing amyloid beta plaques as the neurons were already dying. At that point, the snowball has already rolled down the hill,” says James Peyer, managing partner at the VC firm Apollo Ventures, which focuses on age-related conditions. However, given our limited understanding of Alzheimer’s, selecting the patients that will develop the condition before any symptoms appear could be a big challenge.

But there might be something else behind these failures. What all these trials have in common is that they are based on what’s known as the “amyloid hypothesis.” This theory states that Alzheimer’s is caused by the accumulation of a protein fragment called beta-amyloid, which aggregates to form amyloid plaques inside neurons.

Based on this hypothesis, most Alzheimer’s treatments under development target the formation of these amyloid plaques. But the results of clinical trials seem to indicate that our understanding of Alzheimer’s might have been wrong since the amyloid hypothesis was formulated in the 90s.

Back then, the amyloid hypothesis brought a simple explanation to a condition that was very poorly understood. which may be the reason it quickly became accepted. But following these disheartening clinical results, researchers have started reviewing the evidence backing the amyloid hypothesis and challenging its validity.

Some studies have shown that up to 40% of elderly people accumulate amyloid beta plaques in their brain without showing any symptoms of Alzheimer’s. In one of the failed trials run by Merck, the data showed that the levels of amyloid plaques were reduced with the treatment, but that didn’t translate into an improvement in the symptoms of Alzheimer’s.

Some scientists believe there is indeed a link between amyloid beta plaques and certain types of Alzheimer’s disease, especially those with an early onset. But the evidence on the more common, late onset forms of the disease seems flimsy.

So, what can we do if what we thought was the major cause of Alzheimer’s turns out to not stand up? Luckily, there are already several alternatives underway.

One increasingly popular hypothesis for Alzheimer’s is that it is actually caused by inflammation in the brain, or neuroinflammation. Genetic studies in Alzheimer’s patients have shown the involvement of genes linked to inflammatory diseases such as type 2 diabetes. Therefore, tackling the immune system could be a target to address Alzheimer’s.

“Immunoneurology is an area we’re very interested in, but still at a very early stage,” said Jennifer Laird, Senior Director of Neuroscience at Eli Lilly at the BIO Europe panel. Much like immuno-oncology has started to dominate the cancer field in the last few years, we could soon see the rise of immunotherapy as a treatment for neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s.

Meanwhile, some smaller companies are trying to address the complex genetics of Alzheimer’s by targeting epigenetics — the mechanisms by which gene expression is regulated. A Spanish biotech, Oryzon Genomics, has just started clinical trials with a drug that targets at once two epigenetic enzymes that control multiple genes connected to Alzheimer’s.

In the US, Biogen and Rodin Therapeutics are running preclinical studies with another epigenetics drug. In their case, the target is synaptic resilience. That is, rather than focusing on reducing the loss of neurons, they go after protecting the neurons from losing the synaptic connections between them.

Another area of research gathering attention is the microbiome. The microbes living in our gut are known to influence our brain through what’s known as the gut-brain axis, and they have been linked to mental illnesses as well as neurodegenerative disorders such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

Closely linked with the microbiome is research into metabolism. “This is not yet an area sufficiently mainstream, but we are interested in the link between metabolism and Alzheimer’s. There are preclinical studies going on,” said Jennifer Laird.

One of the most studied links between Alzheimer’s and metabolism concerns cholesterol. Though evidence is scarce, some studies have pointed out that accumulation of cholesterol in the brain could accelerate the progression of Alzheimer’s. A French company called BrainVectis is using this hypothesis as the basis of a gene therapy designed to rescue normal cholesterol metabolism in the brain, and a first clinical trial in humans is expected by 2021.

However, one of the first clinical trials testing gene therapy as a treatment for Alzheimer’s has failed to induce an improvement. Still, the procedure proved safe and it could be tested using different targets that might have an actual impact on the progression of the disease.

Overall, these alternative treatments are still in quite early stages of research, and it is difficult to determine which have the most potential. One thing we still need to significantly improve is our understanding of the disease and its causes before rushing into the clinic.

Images via Shutterstock