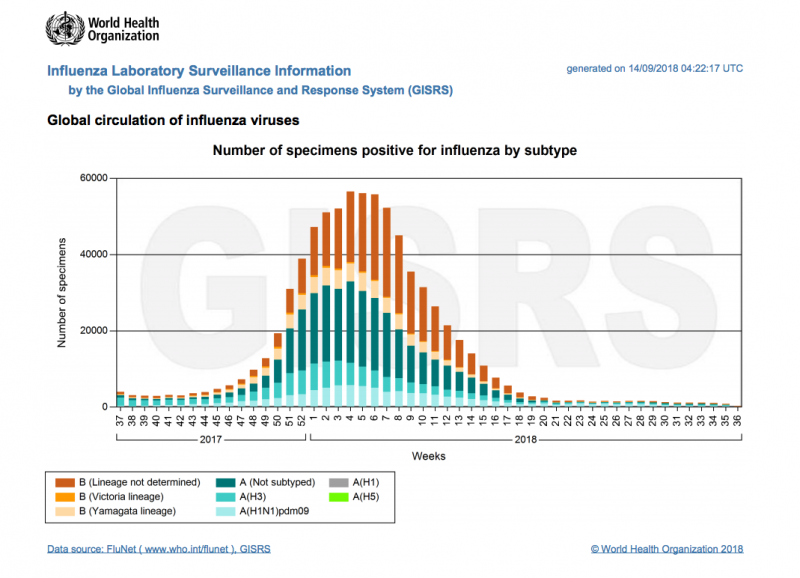

Despite more than a century of scientific endeavour, influenza remains one of the most deadly infectious diseases worldwide. Across Europe, many biotechs are working on novel solutions that could dramatically improve the protection rates offered by current vaccines. Some may even lead to the holy grail of influenza research – a universal flu vaccine.

Each year, ‘seasonal flu’ accounts for around 650,000 deaths. This is mainly because the vaccines we have, simply aren’t good enough. At best, they’re thought to reduce the risk of flu by 40-60%, but some years their effectiveness can be almost negligible. In 2017, flu vaccines offered protection in just 10% of people over 65 in the UK.

The problem may lie with the way flu jabs are produced. Manufacturers currently use millions of fertilised chicken eggs to grow the particular virus strain that the World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted to be circulating during the next flu season. The whole process of growing the viruses and producing the vaccines takes a total of four months.

The problem may lie with the way flu jabs are produced. Manufacturers currently use millions of fertilised chicken eggs to grow the particular virus strain that the World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted to be circulating during the next flu season. The whole process of growing the viruses and producing the vaccines takes a total of four months.

“We’ve been using this same process for 70 years,” says Sean Marett, COO of BioNTech, a biotech company based in Mainz, Germany. “But when the WHO predictions are wrong, and it turns out that the flu strains circulating are different, then you don’t have time to react and create new vaccines because the time windows are so tight.”

Even if the predictions are correct, the vaccines can still end up being ineffective. One of the major problems with growing viruses in eggs is that they sometimes mutate during the lengthy incubation process, yielding the wrong proteins for the recipient’s immune system to target.

However, BioNTech and a number of European biotechs are looking to tackle this by taking completely new approaches to producing flu vaccines, which could potentially change the game.

Making the body produce its own vaccines

In traditional vaccines, antigens are injected directly into the body to induce an immune response. Instead, BioNTech is developing a flu vaccine in which messenger RNA is used to provide instructions to the immune cells to produce the antigens themselves.

The main advantage of an RNA-based flu vaccine is speed. Marett estimates a seasonal RNA flu vaccine could be produced in just a few weeks, which has the potential to save many lives in the case of an unexpected outbreak. “This way, if the WHO finds that the virus has mutated away from their predictions and there’s a risk of a pandemic, you’re still able to produce something to protect populations within the necessary timeframe,” he says.

An RNA-based flu vaccine is also likely to be more reliable, because the process of producing the antigens is done within the human body, rather than in chicken eggs, so there’s no risk of the wrong antigens being supplied to the immune system.

An RNA-based flu vaccine is also likely to be more reliable, because the process of producing the antigens is done within the human body, rather than in chicken eggs, so there’s no risk of the wrong antigens being supplied to the immune system.

Such is its perceived potential that Pfizer have invested €374M into the development of the vaccine, to bankroll a series of clinical trials, starting next year. While BioNTech caution that the technology is still at an experimental stage, there is hope that this vaccine could come to market within the decade, as it works by stimulating the body’s antibody response in a conventional manner and so licensing regulations should be less strict.

“If our trials are successful, I would anticipate we’re talking 6-7 years before this vaccine is approved for use in the general population,” Marett says.

Boosting virus killing T cells

While BioNTech are developing a seasonal vaccine which protects against the current circulating strain, other European biotechs are even more ambitious. They are aiming to produce a vaccine which protects against multiple strains of influenza in one shot, and so only needs to be administered once every few years.

Oxford-based biotech Vaccitech is developing a vaccine which protects against all influenza A strains by targeting the core proteins inside the virus. The limitation of current seasonal vaccines, as well as BioNTech’s, is that they use the surface proteins of the influenza A and B viruses, which are constantly evolving as the viruses mutate.

“The core proteins are very constant,” says Sarah Gilbert, co-founder of Vaccitech. “They’re highly conserved between seasonal flu viruses from one year to the next, as well as seasonal viruses and completely new, potentially pandemic viruses.”

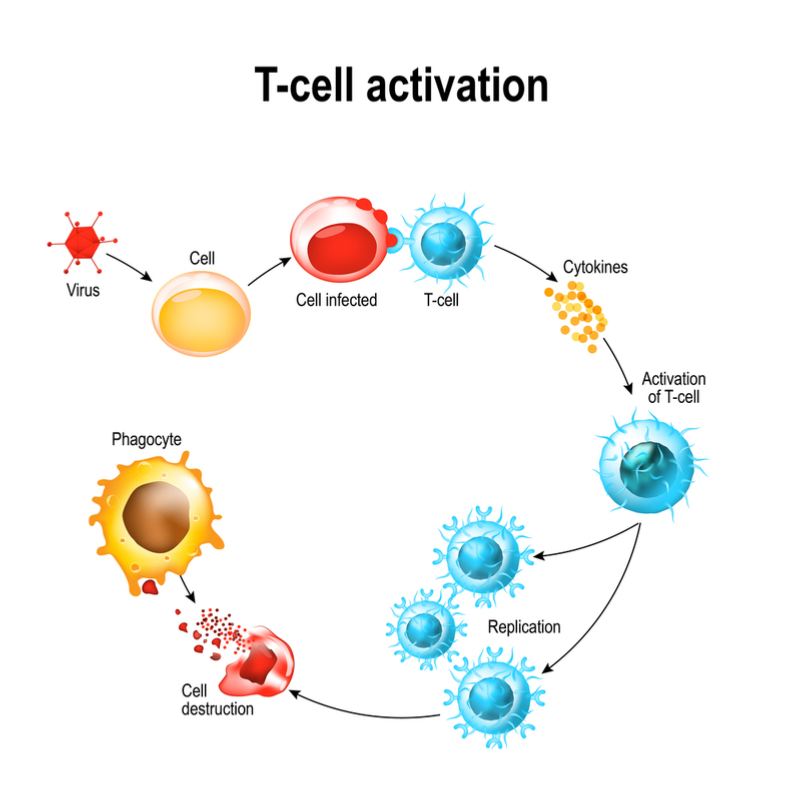

Rather than stimulating the production of antibodies, Vaccitech’s approach works by boosting influenza-specific T cells, which are able to recognise these core proteins and kill the virus before it can spread through the body.

Rather than stimulating the production of antibodies, Vaccitech’s approach works by boosting influenza-specific T cells, which are able to recognise these core proteins and kill the virus before it can spread through the body.

“There’s lots of evidence showing that people who have a high T cell response don’t become ill when they’re exposed to a flu virus,” Gilbert says. “The problem is that people typically don’t have enough T cells when they’re first infected, and it takes the body a while to catch up and make them. With our vaccine, the initial idea is that you would take it before the beginning of each flu season, so the T cell response is boosted and people are protected against all strains of influenza.”

The initial signs are promising. The vaccine has passed safety testing, and after raising nearly €34M of funding, Vaccitech are currently in the midst of a Phase IIB trial of 2,000 individuals aged 65 and over, to be completed in October 2019.

However, Gilbert warns that if this succeeds, it would still take time to get the vaccine licensed. Further large multi-year trials would need to be completed, because it uses a completely different protection mechanism to conventional vaccines. “In the past flu vaccines have been licensed purely because they boost antibody response and it’s assumed that gives efficacy, but we’re working with a different part of the immune system, so we really have to demonstrate that does protect people against influenza,” she says.

Kick-starting the immune system with a genetically modified flu virus

While Vaccitech’s approach could greatly enhance protection, it can’t claim to be a truly universal flu vaccine as it doesn’t protect against influenza B strains. However, Vienna-based biotech Vacthera are trying to create a universal vaccine based on the discovery made two decades ago, that all influenza A and B viruses express a protein called NS1 which enables them to suppress their host’s innate antiviral responses. The rise of reverse genetics techniques over the past ten years has enabled scientists to modify live influenza viruses and delete the NS1 gene.

Vacthera have found that applying these modified viruses to rodents through a nasal spray elicits a powerful immune response, squashing any subsequent infection.

“So far we’ve tested it in mice and ferrets and found it gives an excellent profile of protection against a broad spectrum of both influenza A and B strains after a single intranasal immunization,” says Martin Götting, CEO of Vacthera. “The vaccine is also cheap and has a well established production cycle.”

“So far we’ve tested it in mice and ferrets and found it gives an excellent profile of protection against a broad spectrum of both influenza A and B strains after a single intranasal immunization,” says Martin Götting, CEO of Vacthera. “The vaccine is also cheap and has a well established production cycle.”

Vacthera ultimately hope that a single shot of their vaccine will offer protection against influenza A and B for five years, but they are still in the very earliest stages of product development. An initial Phase I safety trial has been scheduled for spring 2019, and if that succeeds, they will have to raise funding for much larger trials to assess whether the vaccine really does work in the human population.

What next?

With the upcoming flu season expected to be particularly severe, calls for better vaccines are likely to intensify over the coming months. But while it will still be several years before any truly novel products become commercially available, hope is on the way.

As well as the European biotech sector, many pharma companies worldwide are investing millions towards improving seasonal vaccines, as well as the major goal of a universal vaccine. In particular, there is much excitement surrounding Israeli pharma company BiondVax which has completed six successful Phase I and II trials for its universal flu vaccine, based around nine antigens common to almost all influenza A and B strains. Last month, they became the first company to launch a Phase III universal flu vaccine trial, with the results expected by the end of 2020.

With the current flu season marking the 100th anniversary of the 1918 influenza pandemic which killed approximately 100 million people worldwide in just over a year, such breakthroughs are timely. It is impossible to predict when the next major global pandemic may come again, and it would be prescient to fix the current vaccine problems, before it does.

David Cox is a science and health writer based in the UK. He has a PhD in neuroscience from the University of Cambridge and has written for newspapers and broadcasters worldwide including the BBC, New York Times, and Guardian. You can follow him on Twitter @dcwriter89

Images via Shutterstock