Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Scaling up is a problem a lot of biotechs find difficult, both in terms of developing from a small startup to a larger company and also in terms of manufacturing techniques and products. Ryan Cawood, CEO of Oxford Genetics is someone who has tackled both these issues during the last seven years. At our last Labiotech Refresh event in London he spoke to me about how he managed this feat.

Fresh from finishing a PhD at the University of Oxford, Cawood started his company in 2011 and ran it “on a shoestring” for two years before hiring anyone else. The synthetic biology company, which began by making custom pieces of DNA, now employs upwards of 90 members of staff and has a healthy cash flow, an impressive achievement by anyone’s reckoning.

It could be argued that one reason for this success is that Oxford Genetics has responded to market requirements and demand. A key problem for companies producing gene and cell therapies is how to scale up production in a way that minimises production errors and cost. Oxford Genetics has responded to this need by developing an automated robotics platform that can help scale up complex production processes associated with developing and producing gene and cell therapies, vaccines and other biologics on a large scale.

Cawood’s five top tips for how to start and scale up a biotech successfully are as follows.

Have a good idea and prove it has value

Cawood says that persuading people his idea had merit and finding initial funding were the first two hurdles he had to overcome.

“I finished my PhD, but had no money. I convinced the Principal Investigator I did my PhD with to put some money into the company on a handshake. I then took out a bank loan, as I didn’t have any other way to get more money to start the company. Then I went round and met with about 20 different biotechs in the Oxfordshire area and said ‘do any of you need molecular biology services making pieces of DNA? Because I can do that.’”

He had a lucky break, as one of the companies he approached offered to provide him with some lab space in return for doing some work for them making pieces of DNA in his spare time.

He had a lucky break, as one of the companies he approached offered to provide him with some lab space in return for doing some work for them making pieces of DNA in his spare time.

“All of a sudden I had access to this great laboratory for free rent. I still had very little money, but it allowed me to get to the point where I had built the website and started to get some sales.”

Cawood believes this was a turning point for him. “With hindsight you have to prove yourself and get it to a point where you have gone from an idea to a point where an investor or somebody else can come in and say ‘yes, this now has value.’”

Respond to your market and be willing to admit you were wrong

Oxford Genetics began with a focus on synthetic biology. Cawood and his team developed 20,000 different pieces of DNA characterized in different organisms, with a view to selling these to companies that required them.

“We were going out to market and people were no longer as interested in bacteria, yeast, or phage. But what we kept getting asked about was doing work for companies working in mammalian cells. So after about 18 months we pushed the company in that direction.”

They subsequently had a lot of interest from companies developing gene therapy products who were having issues with manufacturing, companies trying to find antibodies for difficult targets and people trying to do gene editing at scale. This led to these three areas becoming the current focus of the company.

Cawood admits that it’s hard when you realize your initial plan may not have been the right one, but emphasized how important it is to respond to your marketplace.

“You will tell yourself this is the right thing to do, there is a market there, there is going to be thousands of customers and it’s going to be really easy to scale and really easy to sell. And after a while you realise that maybe you are wrong, maybe the market is not quite how you thought it was and maybe the customer doesn’t quite want what you have been developing for the last few months.”

“It always comes back to something that Charles Darwin pointed out: ‘It’s not the fittest or the most intelligent, it’s those who are most willing to adapt to change that will survive’.”

Pick a great team and prepare to become a ‘jack of all trades’

“In the early days you are doing everything — the accounts, the web maintenance, making the product, shipping the product, even sweeping the floor, you are doing literally everything. Then at some point you start to get other people in to do these tasks and you have to assess what your role is in the company.”

Cawood strongly believes that a key factor needed to successfully scale up a company is picking the right people to work with.

“You can recognise those people, because they are better than you, which is weird, but it’s great… ideally what you always look for is an employee who is better than you at the thing you are trying to get them to do. That’s the moment when you can let go… and step back and think about the bigger picture… It’s all about finding the right people.”

“You can recognise those people, because they are better than you, which is weird, but it’s great… ideally what you always look for is an employee who is better than you at the thing you are trying to get them to do. That’s the moment when you can let go… and step back and think about the bigger picture… It’s all about finding the right people.”

Something that a lot of biotech founders find difficult is how their role changes as the size of their company increases. Cawood says his role has changed significantly at least four times since he started the company. While he has now reached the point where he can focus on strategy, something more typically associated with the role of a CEO, he emphasizes that was not always the case.

“What I found was that although I don’t now want to be involved in all of the basics of how you run a company, when you are setting it up you should do it yourself. If you bring lots of people in and they understand an area and you don’t then it actually makes it more difficult for you to scale the business, because you don’t understand the problems they are facing. I hate a lot of the things that I’ve had to learn about while building the company. I’m not doing them now, but I know how they work. So I’d say as much as its really painful in the early years it’s actually to your benefit to get stuck in and really learn it.”

Develop a business model that allows you to scale up as easily as possible

“The number of people that are actively looking for the piece of DNA that you’ve got in your catalogue at any given time is quite small. So in the end the market you can get to is relatively modest,” admitted Cawood about his initial efforts.

“But you can start to use that to develop new technologies that you can licence out, or you can use them to modify cells which then turns a £200 sale into a £20,000 engineering project.”

Cawood and his colleagues now try to ensure that every project or job that they do has the potential to make additional downstream revenue for the company. They develop products that can be added to the company catalogue so they are able to make money from future sales. Alternatively, they develop a service or technology that is licensed exclusively to one customer, or that can be used to develop a platform that can be licensed across the industry to 50-100 other companies.

The advantage of a lot of these licences is that they provide annual revenue for the company without annual work input. This means that they help revenue to grow each year without having to double the amount of work required, notes Cawood.

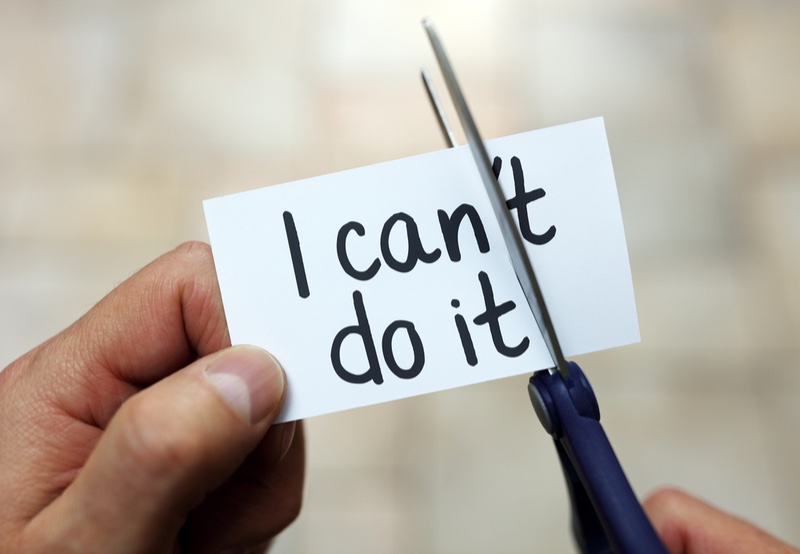

Don’t let the hard times, or academic ‘naysayers’, drag you down

Like a lot of successful people in the industry, Cawood has had to weather the bad times and not let negative thinking get in the way of his company’s progress.

“Just after I did my PhD viva, after 4 hours of being grilled, the external examiner asked me what I planned to do next. Was I planning an exciting career as a scientist in the university? I said ‘No, I’ve started a company. I’m going to do that’. He said, ‘I’ve got one piece of advice for you, you’ll wake up in 5 years and you’ll be miserable.’”

“Just after I did my PhD viva, after 4 hours of being grilled, the external examiner asked me what I planned to do next. Was I planning an exciting career as a scientist in the university? I said ‘No, I’ve started a company. I’m going to do that’. He said, ‘I’ve got one piece of advice for you, you’ll wake up in 5 years and you’ll be miserable.’”

This surprised, but didn’t stop Cawood. He believes the increasing number of spin-out companies from universities such as Oxford in recent years is helping to improve the attitude of the academic community towards the industry.

“It’s definitely changed and it’s changed for the better, but I still think there are a lot of people out there that think that the commercial world is the dark side.”

In addition to developing a thick skin against negative comments, Cawood says it is important not to give in to self doubt and setbacks, an inevitable part of developing and scaling up a biotech company.

“I would say for the first couple of years every couple of days I wanted to quit, but quitting is easy, staying the course is what’s difficult… You just have to keep pushing and keep trying and all of a sudden stuff just starts to come together. It takes ages, but eventually it comes good.”

Listen to the podcast from the event:

Images via Shutterstock and E. Resko

Partnering 2030: FME Industries Report