Despite the popularity of amyloid beta-targeting drugs, none have managed to pass late stage clinical trials, prompting UMC Radboud to halt its own studies.

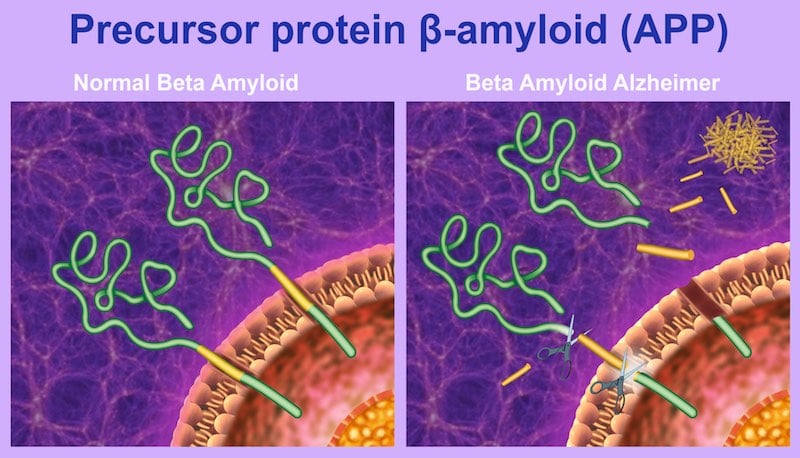

In the latest blow to the amyloid beta hypothesis, Radboud University Medical Centre in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, announced that it will no longer continue studies into drugs targeting misfolded amyloid beta. These proteins clump together and form plaques—one of the telltale signs of Alzheimer’s disease.

Toxic amyloid built up has been the dominant theory of Alzheimer’s for almost three decades, but there is still no drug on the market that can successfully treat the disease by addressing this process. “I simply cannot sell it anymore to my patients,” Marcel Olde Rikkert, Head of Geriatrics at Radboud University Medical Centre, told the Dutch newspaper, De Volkskrant on February 4.

He noted that Alzheimer’s pathology, particularly in older individuals, goes beyond the amyloid beta clumps, adding that, “With elderly people, we often have a mixed picture of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, like Lewy bodies and damage to the blood vessels.”

One of the biggest upsets of the amyloid beta bet came at the end of last year, when Eli Lilly announced that solanezumab, its long-anticipated Alzheimer’s therapy, failed in a late stage clinical trial.

“Eli Lilly’s results were certainly a blow to biopharma’s efforts to cure Alzheimer’s, but this last generation of drugs was aimed at clearing amyloid beta plaques as the neurons were already dying. At that point, the snowball has already rolled down the hill,” James Peyer, a managing partner at Apollo Ventures for anti-aging treatments told Labiotech in December.

Many, like Rikkert, believe that early intervention will likely be necessary to make a significant impact. This is not a trivial task, however, as studies have shown that amyloid beta peptides may start misfolding in the brain even before the onset of any symptoms of disease.

“We should start as early as possible,” Hendrik Liebers, CFO of the German Alzheimer’s biotech, Probiodrug, told us last December. “But there is such a thing as too early. The problem is, how do you run a clinical trial for a preventative medicine? In order to show a disease is treated or cured, there has to be a disease to start with.”

Some studies have raised questions about whether targeting amyloid beta would work at all. One 2008 Lancet study, for example, found that clearing amyloid plaques from patients’ brains did not improve prognosis. In 2015, another group of researchers reported in Nature Neuroscience that treating mice with an antibody against amyloid beta did not improve neural function, and in some cases, actually made it worse. While these studies cannot disprove the amyloid beta theory, they do suggest that there is more to the equation.

Still, a number of biotechs, including Biogen and Probiodrug, continue to place their bets on drugs that target amyloid beta. “Unfortunately, there has always been something of a sheep mentality in the pharmaceutical industry,” Peter Roberts, a pharmacologist at the University of Bristol, told Chemistry World.

“Follow a theory, spend loads of [money] trying find a drug and then, if it doesn’t work or produces serious side effects, dump the programme. What is needed is a much more holistic approach to the whole disease, rather than trying to compartmentalise it neatly within an ‘amyloid hypothesis,’ a ‘Tau hypothesis’ or anything else.”

Images from Henkje, Alexilusmedical, Styve Reineck / shutterstock.com