Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

A bioart exhibition explores the essential role that linen has played in the science of microbiology throughout history.

Along with beer, linen is one of the oldest biotechnological products. Since its origins in ancient Egypt, bacteria have been responsible for retting, a process in which the linen fibers are separated from the stem of the flax plant. But the link between linen and bacteria goes well beyond that.

“Linen is integral to the history of microbiology,” says artist Anna Dumitriu. “Van Leeuwenhoek, who created the first microscope, was a linen draper. And the reason that he knew how to create the lenses was because he was used to look at the thread count to check the quality of linen.”

Dumitriu is a bioartist, working at the intersection between art and life sciences. Her latest exhibition, called From the Field, showcases the many times throughout history that this textile has been essential to the field of microbiology. And it does so through artworks made of both linen and bacteria. Let’s take a look at her latest work.

Pastorianum

“Sergei Winogradsky was a microbiologist from Russia and a contemporary of Louis Pasteur,” explains Dumitriu. “He thought you had to look at the whole microbial ecosystem rather than try to grow bacteria in isolation. We know now that that is very much the case, but he was ahead of his time.”

“He also discovered the first nitrogen fixing bacteria as part of his investigation into linen. It was called originally Clostridium pastorianum, and a few years later changed its name to Clostridium pasteurianum, in honor of Pasteur.”

The original name of this bacterium translates to “spindle from the field,” which Dumitriu used as inspiration for the title of the exhibition, playing with the word “field” as the multiple areas of study in which Dumitriu is involved with during her artistic process.

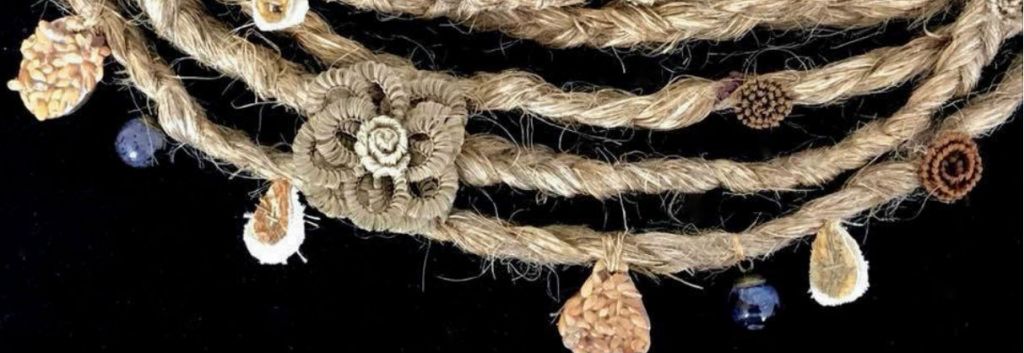

Inspired by the role of this bacterium in the history of microbiology, Dumitriu created Pastoranium, a necklace made out of flax. Threaded in, one can find glass beads with live Clostridium pastorianum in it, as well as pieces of cloth died with bacteria grown in a device that Winogradsky designed to study microbial ecosystems.

The necklace is also decorated with seeds that resemble by the shape of Clostridium bacteria, and with antique wreaths made of human hair that were used in mourning in Victorian times.

Spindle

That nitrogen-fixing bacterium discovered by Winogradsky is closely related to Clostridium difficile, a species that can cause very severe bowel infections. And it also has a fascinating history behind it.

“It was called difficile because it was hard to grow, not because it is hard to treat,” says Dumitriu. “It didn’t use to be a human pathogen, it was part of the healthy microbiome. In 1972, when certain antibiotics started to be used, it took on drug resistance and became a human pathogen.”

The artist was inspired by the work of the Healthcare Associated Infection research group in Leeds. The researchers have developed a model that replicates the conditions of the human gut to study C. difficile and the effects of different antibiotics.

In one of the chambers, the researchers study the formation of biofilms — protective structures produced by the bacteria encased within them that can confer resistance to antibiotics.

Dumitriu replaced the glass rods used to grow biofilms with long strings of linen crochet. The biofilm growing on them made the linen strings solid, turning them into small three-dimensional sculptures that resemble the spindle shape of the bacteria. After sterilizing them, the artist threaded them into an antique linen lace collar.

Clean linen

“Linen is one of the few fabrics of the old days, along with wool and silk,” says Dumitriu. “You can’t wash silk and wool because they were too fragile. Linen becomes stronger when wet, so you can absolutely give it a bashing down by the river or hit it with a rock to clean it, and you can boil it.”

“This meant that linen became associated very strongly with the idea of cleanliness. People would wear very clean linen clothes and this would mean that they were clean,” she explains. “You didn’t wash your body, you’d catch a cold. But you could wear linen and it would leach the disease out of your body, then you could take that away and wash that.”

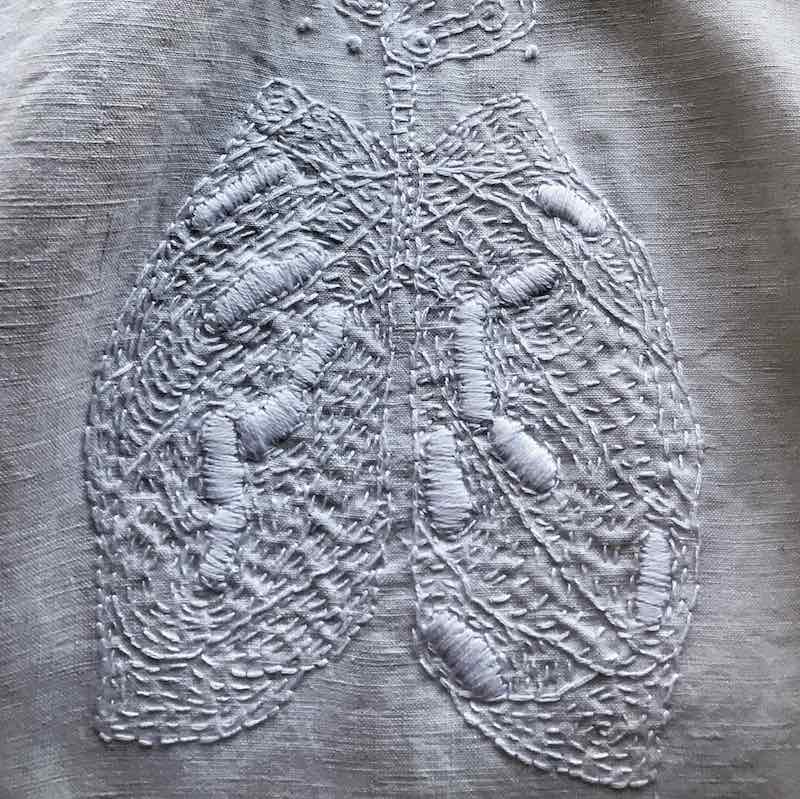

Fascinated by this concept, which seems to have originated in France, Dumitriu found a 19th-century linen nightgown to use as the canvas of Clean linen. On it, she embroidered designs representing the pathogens responsible for the diseases of those times.

On top of the lungs, one can find the bacterium that causes tuberculosis. Under the arms is Yersenia pestis, responsible for the plague; around the neck the bacterium behind diphtheria; and on the stomach is the Streptococcus that causes scarlet fever.

“Those patches of embroidery are impregnated with the actual DNA of those organisms,” says Dumitriu. Working with scientists from the National Collection of Type Cultures, and the Modernising Medical Microbiology group at the University of Oxford, she extracted the DNA from killed samples of these pathogens.

“It’s a huge thing for me to work with Yersenia pestis, an organism that has changed history, cultures, and whole politics,” she told me.

The history of linen and microbiology are closely interwoven, but we rarely look at them together as they are so often seen as completely different fields. The art of Anna Dumitriu exposes the hidden links in the form of beautiful objects that make the connection between history and modern science tangible.

These artworks are on show at the R-Space Gallery in Lisburn — which used to be the heart of the linen industry in Northern Ireland — until September 7th, 2018. Along with them, Dumitriu will be exhibiting some of her previous work using linen and bacteria, including a wartime suit impregnated with genetically-engineered bacteria.

Images via Anna Dumitriu