Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

The close of the UK firm Achilles Therapeutics’ €146.9M ($175.5M) initial public offering last month may have been a long-delayed starter pistol for investments into neoantigen-based therapies, a family of personalized cancer immunotherapies that target proteins unique to an individual’s tumor.

Neoantigen-focused companies have closed smaller initial public offerings (IPOs) in the past. Two major examples in 2018 were an €80M ($95.6M) net raise for the US firm Gritstone Oncology and a €75.2M ($89.9M) IPO for its compatriot Neon Therapeutics. But the Achilles close, following a series of fundraising announcements over the past six months for younger neoantigen companies, could be a sign that investors are warming up as never before.

Investors had soured on the neoantigen space following some late-stage clinical failures in therapies targeting tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), says Cedric Bogaert, co-founder and CEO of myNEO, a bioinformatics company in Belgium that identifies neoantigens. TAAs are commonly present in multiple types of tumors, making them attractive therapeutic targets for drug developers. But some can also be found in healthy tissue, raising the risk of off-target effects.

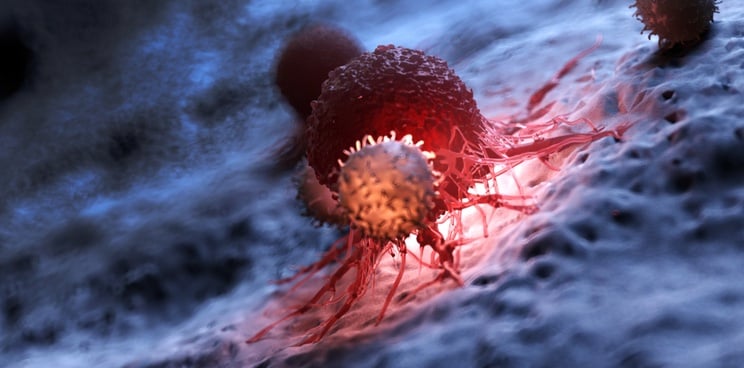

The newer generation of personalized therapies are targeting neoantigens, a type of tumor-specific antigen (TSA) that appear in tumor cells over time as mutations accumulate, changing proteins that are expressed on the surface. Identifying patient-specific neoantigens has been a logistical challenge, but recent advances in bioinformatics have made the process more manageable.

myNEO has developed a bioinformatics platform to validate neoantigens that partner companies tap to identify personalized targets for individuals in clinical trials. Earlier this month, myNEO announced a partnership with sequencing company OncoDNA to design personalized vaccines against cancer neoantigens based on messenger RNA (mRNA). Largely thanks to vaccine efforts against the Covid-19 pandemic, mRNA therapeutics themselves have jumped into the mainstream in the last year.

Using its own bioinformatics platform, London-based Achilles Therapeutics is targeting neoantigens via a T-cell therapy approach. The method consists of extracting immune cells that have invaded the patient’s tumor known as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). The company is then able to identify, expand, and reinfuse those TILs that target the patient’s unique clonal neoantigens — those that appear early in cancer development and are therefore more likely to appear in most of a tumor’s cells.

Achilles’ two lead programs are in phase I/II testing for advanced non-small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

The Belgian mRNA specialist eTheRNA used similar ex vivo approaches to validate its technology in a phase I/IIa study of patients with advanced melanoma. There are technical challenges to overcome with this method, however. According to eTheRNA’s Vice President of Business Development, Michael Mulqueen, “it’s still a bit of an art, how you get the cells to proliferate outside of the body.”

eTheRNA encodes neoantigens into mRNA vaccines, which it is developing as off-the-shelf cancer immunotherapeutic vaccines. The company plans to test the technology in a phase I/IIa trial as a cancer monotherapy and in combination with an immune checkpoint inhibitor later this year.

Personalized combination therapies will be necessary to improve cancer treatment, says Mulqueen. Checkpoint inhibitors, for example, effectively cut the natural brakes on T cells that some cancers exploit, leading to remarkable responses in some patients. But they don’t work for the majority of patients or for every tumor type. Neoantigen therapies may be complementary to checkpoint inhibitors, priming the immune system by boosting its ability to distinguish cancer cells from healthy ones.

Other patients might respond to different treatments, such as cell therapies. “Not everybody will necessarily get every type of therapy. The physician will work with the patient to blend the right system together,” Mulqueen adds.

Investors may be warming in part because costs are becoming more manageable, particularly for less specialized approaches. However, Mulqueen says the therapies will never be cheap, “no matter how sophisticated you get. But they’re addressing some very deadly diseases, so there’s a balance there we have to strike.”

eTheRNA raised a €34M Series B round last year, which will fund the company for at least the next year. As it looks to the future, Mulqueen thinks Achilles’ IPO shows there is an appetite from investors for neoantigen therapies. “Achilles has probably timed its IPO quite nicely,” he says. “Maybe if it had tried this maybe eight years ago, investors would have said ‘cell therapies? A bit too risky.’”

But demand for cell therapy manufacturing in the past year has increased dramatically, along with companies innovating in the space, raising hopes of lowering costs and expanding access to personalized cell therapies targeting neoantigens. “Everyone’s more willing to take this as a usable therapy now,” says Mulqueen.

“In the past year, due to Covid-19, everything involving the field of immunotherapy has received a big boost,” says Bogaert. “Achilles’ IPO was a sort of side effect, but it also brings along a wave of good news for immunotherapy. It shows recognition that it’s a very promising technology field.”

Cover image from Elena Resko

Oncology R&D trends and breakthrough innovations