Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

The first vaccine against coronavirus disease could one day be made of mRNA. How is mRNA showing promise against the pandemic, and what could it signify for the mRNA field?

The global number of coronavirus disease (Covid-19) cases has passed 600,000 and is threatening to bring healthcare systems worldwide to their knees. To control the pandemic, more than 50 vaccine development programs are in progress around the world. They are based on a wide range of technology, such as RNA, DNA, viral vectors, and proteins.

Of the many types of vaccine technology in development to tackle Covid-19, RNA — particularly that based on messenger RNA (mRNA) — is one of the frontrunners. The most advanced of the mRNA vaccine programs in progress is that of the US mRNA giant Moderna, which is one of just two at phase I so far — the other being a viral vector developed by CanSino Biologics in China.

Some of Moderna’s closest mRNA vaccine rivals in this race are in Europe. For example, the German giant BioNTech recently teamed up with Pfizer to take a Covid-19 mRNA vaccine to phase I in April. Another German company, CureVac, is developing its own Covid-19 vaccine with the non-profit Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI). It expects to reach phase I in early summer.

Other European companies also declared mRNA vaccine programs for Covid-19 last week, including the Belgian firm eTheRNA, the French big pharma Sanofi, which teamed up with the US mRNA company Translate Bio, and the Belgian mRNA startup Ziphius Therapeutics.

The field of mRNA therapeutics is still relatively untested, with no mRNA vaccines or other therapeutics yet approved. In spite of this, companies developing mRNA technology have received a lot of interest, and have even been the center of an international tug-of-war. So why could mRNA be a big deal in this pandemic?

The biggest advantage of mRNA therapeutics over current vaccine technology, such as weakened viruses and proteins, is the speed of production at times of emergency.

Just take preclinical development, for example. Here, vaccines take on average around 18 months to design and get to phase I testing. This is because the complex proteins or weakened viruses making up the vaccine need to be designed, produced, and tested in the lab.

In contrast, Moderna took little more than two months to enter phase I after the coronavirus’ genetic sequence was released in January. Its closest rivals, BioNTech and CureVac, are gunning for phase I within the next three months.

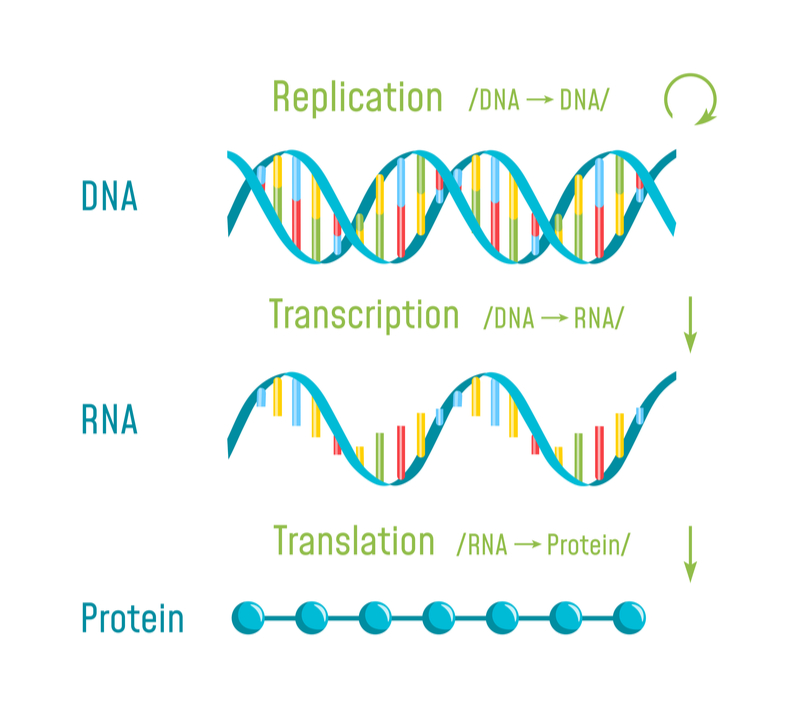

“mRNA is an information molecule and we design our mRNA vaccines using the sequence of the virus, not by working on the virus itself,” wrote Moderna on its website.

It must be noted, though, that Moderna began the clinical trial with fewer animal testing data than the average vaccine to enter phase I, which the company justified with the urgent situation at present.

The industrial production of mRNA molecules is easier and faster than more complex drugs because mRNA molecules are simple chains of nucleotides that encode proteins when delivered to the cell. This way, the patient’s own cells become the drug factory, rather than man-made facilities.

Even so, despite the faster development times, the mRNA vaccines will still need to undergo the same clinical trial process as every other drug, which could take more than a year.

Many of the production advantages of mRNA over proteins and viral vectors are shared by vaccines made from DNA. DNA vaccines are also hot on the Covid-19 case, being developed by several companies around the world, such as the US Inovio Pharmaceuticals, which aims to start phase I in late April, and a pan-European consortium announced today involving the UK company Cobra Biologics.

However, according to Ziphius’ CEO, Chris Cardon, mRNA molecules are better at activating the immune system than DNA molecules, which is what you need in a coronavirus vaccine. Wim Tiest, spokesperson for eTheRNA, added that vaccines made of mRNA can be better at accessing cells than DNA, and also potentially safer than delivering foreign DNA into a patient.

“mRNA offers the additional advantage that it can be taken up directly by the cells of the immune system without additional stimulation, and carries no risk of integration of the product into the genetic material of the target cells,” Tiest told me.

The development of mRNA drugs has been in progress for decades and has drawn big interest before. However, this is still an unproven technology. For companies in the field, the Covid-19 pandemic could be a big opportunity to prove the potential of mRNA vaccines.

“It is becoming increasingly clear that the biggest challenge for mRNA and other vaccine technology platforms is that conventional clinical development paths are far too lengthy and cumbersome to address the current public health threat,” Ziphius’ Cardon told me.

Cardon continued, saying that both companies and regulators are learning from this pandemic and are striving to find ways to streamline the approval process, and maybe even accelerate the approval of vaccines against Covid-19.

“[A Covid-19 vaccine] could be the proof of concept for mRNA technology in the market. If successful, it could be the starting point for several other mRNA-based drugs in the future,” Thorsten Schüller, Director of Communication at CureVac, told me.

In addition to regulation, the pandemic is helping the mRNA field by increasing the already abundant investor interest in companies developing this technology.

For example, Moderna and BioNTech stock prices on the Nasdaq are over 50% higher than they were before the pandemic arrived. BioNTech also has two partners supporting its programs: the big pharma giant Pfizer, and the Shanghai-based Fosun Pharma. Fosun’s interest resulted in a deal worth up to €120M.

CureVac, a private company, has also been the recipient of increased funding from its CEPI collaboration. Additionally, the company received €80M funding from the EU after a dispute erupted over a rumored acquisition offer by the USA, which CureVac strenuously denied.

“There is a clear recognition that this broad technology is at the forefront of future vaccines. The current pandemic will only reinforce this position,” eTheRNA’s spokesman Wim Tiest said.

Even with big support from investors and regulators in the pandemic crisis, developing a vaccine for Covid-19 will still be a huge challenge. The biggest reason for this is the immense work required to get it to market as fast as possible.

“The current and immediate challenge is with the timelines around vaccine development that are under huge pressure because of the urgency, and the immediate need of large financing to support the programs,” Tiest explained.

Not only do they need to push out a vaccine in record time, companies also need to make sure that their vaccine can succeed in clinical testing. This is no easy feat, as an analysis from 2013 estimates that the average vaccine has a 6% chance of entering the market starting from the preclinical stage. The likelihood of an mRNA vaccine reaching the market for Covid-19 is unknown.

“In this special case, speed is an important factor – but speed combined with making a high-quality product,” Schüller said.

Even if the vaccine works well against the pandemic, an additional challenge presents itself: making sure that the vaccine works against multiple strains of the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19, called SARS-CoV-2.

“The second biggest challenge is to build a vaccine that – when it comes out in one to two years at the earliest – is still relevant against the coronavirus that will be around by then,” Tiest explained.

“The current virus could have shifted and mutated, or a new and future outbreak could display a viral variant.”

Taking into account all the challenges, Covid-19 could yield big rewards for mRNA as a field. If an mRNA company manages to pull off the achievement of getting a coronavirus vaccine to the market, things could look a lot brighter for companies developing mRNA treatments.

“If mRNA drugs can prove their safety and efficacy on the market we will probably see much more mRNA medicines in future,” Schüller told me. “Due to its different approach than ‘normal’ drugs, they have the potential to revolutionize medicine.”

Images from E. Resko and Shutterstock