Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

Thomas Meyer, CEO of Auris Medical, discusses how biotech can finally bring solutions to those who live with hearing loss, tinnitus and vertigo.

Thomas Meyer is at the forefront of a wave of drugs that could, for the first time, show efficacy in treating common hearing disorders. In 2003, he founded Auris Medical to address the lack of effective treatments for conditions such as hearing loss, tinnitus and vertigo.

The company is expecting imminent results from a Phase III trial that could lead to the approval for the first therapy for sudden deafness, the most frequent type of acute hearing loss – in Europe, it affects almost 5 out of 10,000 people.

“Actually, when you look at ear disorders, they are even more frequent than eye disorders,” Meyer told me. “And still, they are a blind spot in medicine.” Curious to learn why it has been so challenging to treat hearing disorders in the past, and how biotech companies like Auris could finally put a stop to it, I asked Meyer about his journey, from creating a new technology from scratch to the brink of approval.

Thomas, how come there are no effective drugs available for hearing disorders? Is that why you decided to create Auris Medical?

Definitely. There are absolutely no FDA-approved drugs, and some older drugs licensed in a few European countries. There is relatively widespread off-label use of steroids, of vasodilators, but none has actually been tested rigorously for efficacy in inner ear disorders. Effectively, there are no specific inner ear therapeutics on the market.

I was really intrigued by the complete lack of treatment options for people with these problems. People around me suffered from tinnitus or hearing loss, but they never spoke about it. One acquaintance once told me that when he listened to certain keys on a piano, he heard zero sound. That was because his tinnitus was about at that frequency. I asked him why he hadn’t said that before and he told me: “Why should I talk about it? I have had this for 20 years now. The more I talk about it, the more I think about it, and the more I hear it. I just have to live with it.”

I eventually figured out the reason why there were no drugs available was actually a classic situation: big pharma had been just too used to systemic delivery – pills, tablets, etc. If you try to treat inner ear disorders systemically, it’s impossible, in many cases, to get meaningful concentrations to the inner ear. You would need a very high dose, which can lead to side effects.

But a group at Inserm had done quite a lot of very good, exciting work in glutamate receptors in the inner ear. They had some good ideas, and they were eager to see them move into the clinic. So I decided to start my own business, and Auris Medical was born.

We focus on three acute inner ear conditions, which we estimate to have a worldwide market potential of $3Bn. The reason why we focus on acute hearing loss and acute tinnitus is because we understand the biology. Chronic conditions are a much bigger challenge, with a much bigger market potential, of course. But you’d better not start with the most challenging step.

Auris Medical is about to release Phase III data for a potential first treatment for acute hearing loss. How are you treating this condition?

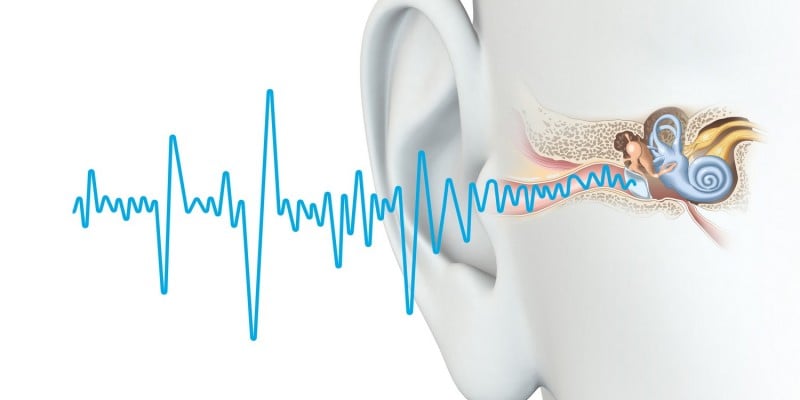

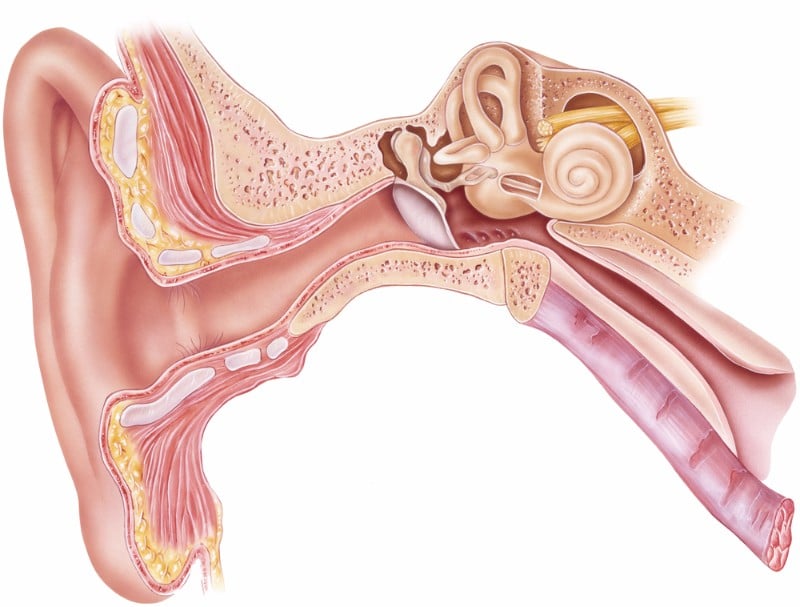

Both acute hearing loss and tinnitus can be triggered by an injury to the inner ear. Think of firecracker accidents, of a sudden change in pressure when flying or diving – called a barotrauma –, an infection, or a disruption in the blood supply to your inner ear.

When that happens, some of the damaged cells die right away, and they will never recover. When you are born, you have the maximum number of sensory cells, called hair cells, and neurons. And from there, there’s only one way to go, which is down.

But within the first four weeks, some cells can still recover naturally – some birds can actually regrow these cells after four weeks, but not humans. We try to protect these cells from dying and allow them to recover using a peptide called D-JNKI-1, or brimapitide, which can enter the sensory cells using Tat, a peptide transporter derived from HIV research. Once inside, brimapitide blocks the JNK MAPK stress pathway that ultimately leads to apoptosis – programmed cell death – of the sensory cells.

Now, this has to be given relatively early. We have been conducting our clinical trials within the first three days after acute hearing loss with this treatment, which we call AM-111. We expect results from the first of two Phase 3 studies with AM-111 very soon. We enrolled a total of 256 patients with sudden deafness, and measured hearing recovery from baseline to day 28. The goal is to show statistical significance in improving upon the natural recovery process, meaning an improvement of at least 10 decibels over placebo. Decibels are a logarithmic measure, so 10 decibels mean that you can hear sounds that are half as loud.

In Phase 2, we showed a rapid recovery of hearing that was already significant after 3 days with a single dose of AM-111. If we can confirm what we saw there, we will start discussions with the EMA and the FDA next year. We’ve got orphan drug designation from both those agencies, so approval could happen as soon as 2019.

Update (28/11/2017): Auris Medical failed to meet the primary efficacy endpoint of its European Phase III trial with AM-111 and will terminate early a second trial in North America and the US. The company is considering to seek approval despite the results.

What could make this approach work where others don’t seem to have succeeded before?

We are using a local delivery approach where a physician injects the drug into the middle ear. This technique, called intratympanic injection, has been around for several decades. But in the past, it was always used with liquid solutions.

And when the patient swallowed, they drained off through the Eustachian tube. We use a viscous gel formulation to ensure the drug stays in the right place and diffuses into the inner ear through the round window, a tiny membrane that communicates with the inner ear, just a few square millimeters in surface.

There are also fantastic, sophisticated hearing aids out there that keep getting better and better. But if you can preserve your natural hearing, that’s simply better. The truth is that hearing aids cannot know what sound you want to focus on and distinguish it from background noise.

You’re also treating tinnitus and vertigo – how?

In the case of tinnitus, the therapeutic time window is longer than for hearing loss – from about 3 months up to 6 months. Tinnitus is triggered by the glutamate receptors, or NMDA receptors, inside the inner ear. After an acute injury, they become hyperactive and generate a phantom sound inside your inner ear.

We block that NMDA receptor activity, in order to allow the auditory system to readjust and rebalance, using esketamine, a drug that is structurally very similar to the anesthetic ketamine. It’s a safe drug and we are using minimal concentrations thanks to local delivery.

We had, unfortunately, a setback with that program last year. We failed to show significant differences for the entire study population, though we saw efficacy in some sub-groups. This was due to trial design issues; when you measure tinnitus, unlike in a hearing test where you hear and react to tones, it’s much more subjective, relying on patient-reported accounts.

We’ve changed the protocol and the questionnaire, and we feel confident that we will have a very good chance of demonstrating the efficacy of Keyzilen, which also got fast-tracked by the FDA. We expect to have results from a Phase 3 trial in February.

Our third program, AM-125, which is in Phase I, is a little bit different. Here, we are talking about vertigo, a sensation of movement even when there is no movement. It’s also kind of phantom perception.

There have been some older drugs around for quite some time – basically antihistamines that sedate the whole vestibular system. But they have one big disadvantage, which is that though they help you in the very short run, they delay the recovery of the sense of balance.

We use betahistine, a drug that has been around since the 1960s in oral form. But its oral bioavailability is very low, of about 1%. Nowadays, nobody would seek to develop a drug with such a low bioavailability, because it implies a lot of variability from patient to patient. But by delivering betahistine through the nose, we could give a very significant boost to its efficacy.

You’re not the only ones trying to treat ear disorders. Who are your competitors?

Back when we began in 2003, we were the first kid on the block, so to speak. But since then, a few other companies got started. There’s Otonomy in the US, which had a major setback quite recently – a Phase 3 in Ménière’s disease – whose symptoms include vertigo, tinnitus and hearing loss – of that showed zero difference between placebo and treatment. They do have one tinnitus program that completed Phase 1, so they are relatively early in the game here. There is a UK company called Autifony, a spinoff from GSK. They use systemic delivery and did a Phase 2 in tinnitus and another in hearing loss, which both failed.

Then, there is a French company called Sensorion, which has one drug for vertigo in Phase 2 and also works on systemic delivery. There is a private US company called Sound Pharmaceuticals, working more on the prevention of short-term hearing loss. And another company called Decibel Therapeutics, based in Boston, that is very early stage.

Novartis works with GenVec to regenerate hair cells in deaf cochlea, and there is a Phase 1 study going on. There is Roche, which has an early stage collaboration with a company at Stanford. There is one named Audion, in the Netherlands, that’s also relatively early stage. And another company in Basel, called Strekin, which is repurposing a diabetes drug.

However, there has been no drug approved yet. So, if AM-111 and AM-101 are successful, they clearly have the potential to become the first approved inner ear therapeutics.

How are you feeling being so close to the finish line?

Oh, well, it took a bit longer than I had initially assumed, but I think that’s classic. When we started, there were no best practices, no guidelines. We had to build it from scratch. Sometimes it was two steps ahead and one step back. Or even three steps backwards.

I compare it to long-distance running, which is one of the few hobbies I still have some time for. You know it’s going to take a long time, and you need stamina. There are times when your batteries are running low and you need another push. But, overall, it has been an extremely exciting time.

Images via Auris Medical; Krankheiten Portal; Medical Art Inc / Didesign021 / Darren Baker /Shutterstock