Newsletter Signup - Under Article / In Page

"*" indicates required fields

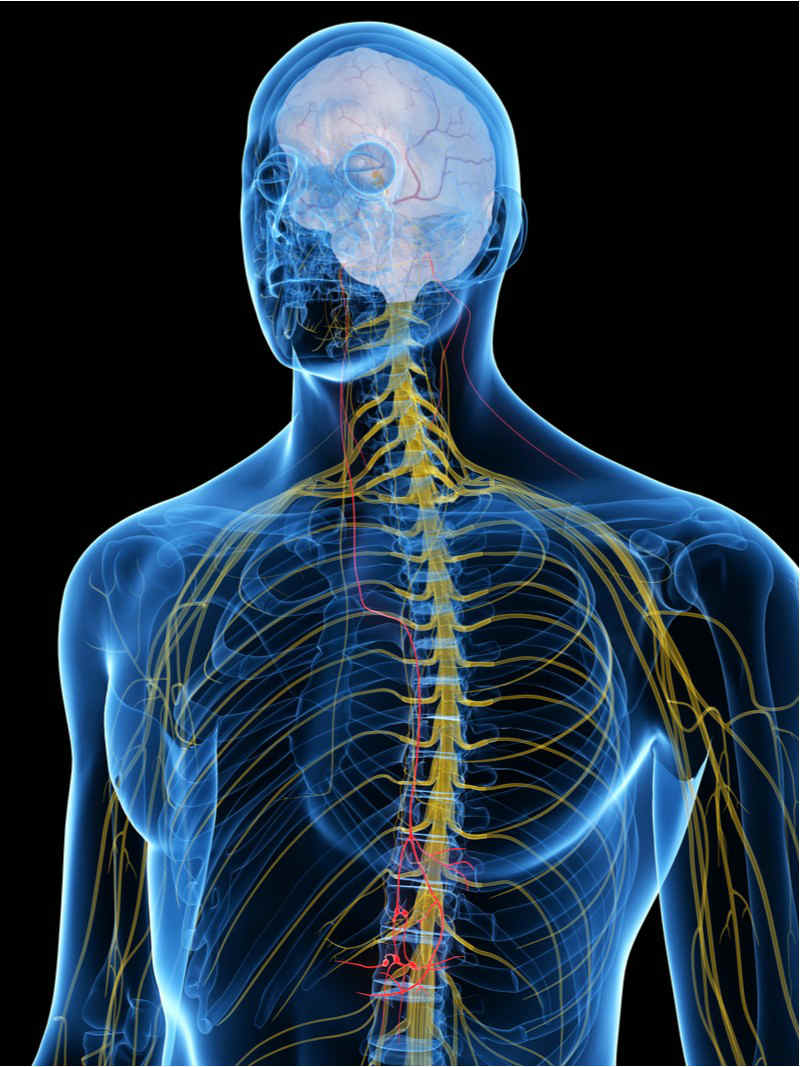

We fly to Lomazzo, Italy, this week to visit Silk Biomaterials. As the name implies, the company is testing different medical applications of silk, such as in nerve repair.

Mission: Founded in 2014, Silk Biomaterials uses silk as a scaffold material for medical applications such as vascular grafts and peripheral nerve repair.

In many tissue repair procedures, the current gold standard is grafting with similar tissue from elsewhere in the patient’s body. This comes with drawbacks such as limited tissue availability, and size and shape mismatches.

One alternative for grafting is inserting artificial scaffolds into the site to provide a guiding environment in which the tissue can heal. The ideal scaffold materials are porous to allow cells to enter, biodegradable, and non-toxic. Furthermore, some scaffolds can come seeded with cells or treated with chemicals to improve the regrowth process.

As the CEO and co-founder of Silk Biomaterials, Gabriele Grecchi, told me, silk is not just good for pyjamas: it has great potential as a scaffold material. “It can be easily purified and processed into different 2D or 3D shapes,” he explained. Unlike some other scaffolding materials, the company says that silk also requires no seeding with cells nor chemical treatments because the material encourages cells to enter the material and grow.

The company produces its silk from the web-slinging silkworm Bombyx mori and isolates a protein called silk fibroin from the natural product. It then spins the silk fibroin into microfibers and nanofibers.

By using different sized fibers, the company can tune the resulting silk fibroin scaffold’s biomechanical properties just by changing their proportions in the mix.

Silk Biomaterials’ most advanced indications for its silk fibroin scaffold is in peripheral nerve damage, with a first-in-human trial due to begin this month and estimated to finish in 2020. Grecchi told me that the trial will help the company to get approval for the market in the EU, while discussions are ongoing with the FDA regarding getting the regulatory process started.

The second indication is in blood vessel damage, with preclinical studies due to finish in six months. “We are steadily progressing with the preclinical development in the vascular graft and orthobiologics areas, where we have already collected very promising results,” Grecchi said.

The company raised €7M in a Series A funding round in 2016, with help from a Horizon 2020 project, which was aiming to advance its development of a silk alternative to current arterial grafts.

What we think: Silk as a biomaterial could provide a neat alternative to current grafts, which can be problematic, and sometimes not even possible. According to the company, using silk would also be cheaper than other biomaterials and more compatible with the surrounding tissue.

Silk remains in the early development stage as a surgical material and is going to need considerable clinical development before it can be approved for the market.

Silk as a medical material is receiving a lot of attention in European biotech. In the UK, Oxford Biomaterials is targeting nerve repair and vascular grafts with its own processed form of B. mori silk. The German biotech AMSilk produces synthetic spider silk using engineered E. coli and, alongside making biodegradable sneakers for Adidas, hopes to use the silk to coat breast implants to reduce inflammation and fibrosis after implantation. Another Italy-based biotech called Silkfusion is using a silk scaffold to develop a platform for manufacturing human blood platelets.

Silk may not be the only answer to replacing tissue grafting, as other companies have the nerve to try other materials. A synthetic polymer implant sold by Dutch company Polyganics is designed to aid nerve growth. In Sweden, BioArctic is staging clinical trials for a biodegradable device intended to aid nerve regeneration in spinal cord injury.

Images via Shutterstock